|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

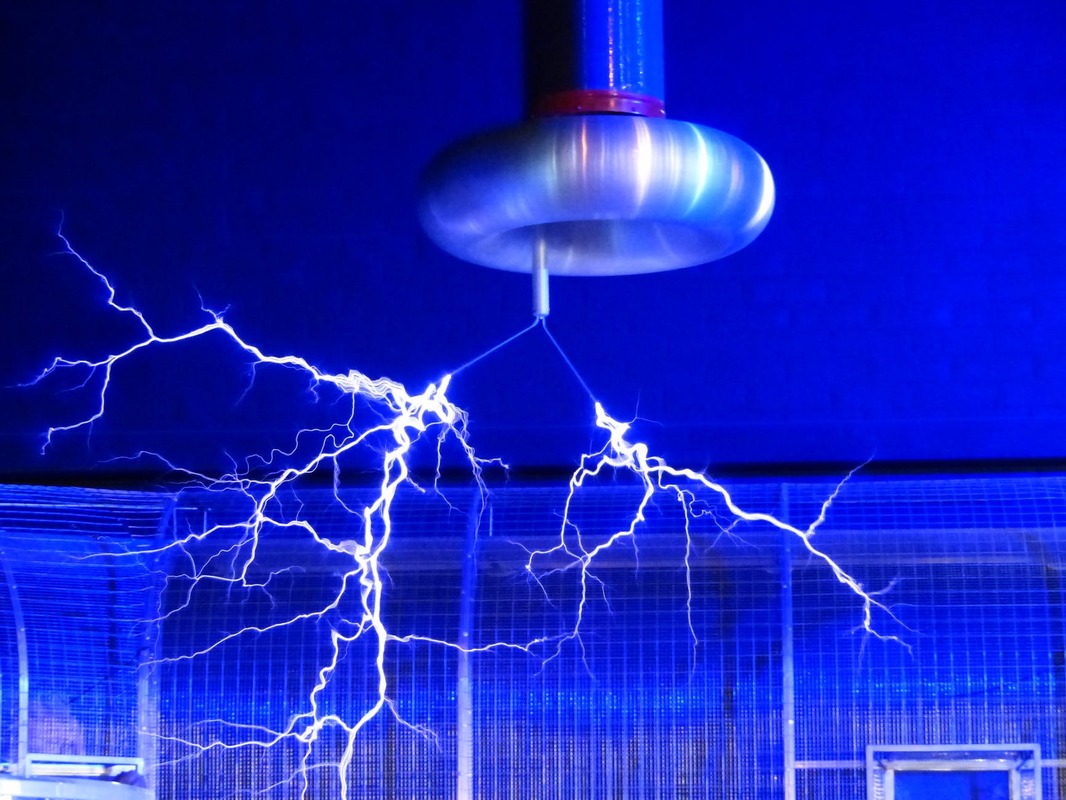

The Last OneBy Vivian Rachelle Joseph Lombardi, S.J., killed me by electrocution accidentally, but more importantly, hypothetically. Like all freshmen at Saint Joseph’s University, I took Philosophy 154. Unlike all freshmen, my professor hypothetically electrocuted me. He described my death to the class while holding an Expo marker in one hand and a handkerchief in the other. He wanted to demonstrate the effects of what he called The Light Switch Case. In this example, a person wants to read and needs to turn on a light. However, turning on the light will electrocute another person. Father Lombardi didn’t think this was interesting enough, so he was the person trying to read, while I became the person whom he electrocutes. He announced to the class “Ms. Milan is dead. I have killed her. She is gone. What do we think of her death?” The silence of my classmates and my cheeks burning with embarrassment warranted a frantic phone call to my mother after class. I was mortified. My mother assured me it was nothing personal, that philosophy professors are just weird. She told me not to worry about it, but how could I not? Father Lombardi was an older gentleman, who told us to do the math when he said he’s taught at St. Joe’s for over 40 semesters. He had an odd sense of humor and a fantastically vivid sense of imagery. Once when he lost the focus of our class he asked, “If I throw babies in a wood chipper, is that moral or immoral?” He read his professor evaluations to us from previous semesters which spanned from “this class isn’t that bad, people just don’t do the work” to “I feel like I’m falling in love with my rapist.” Two of his personal favorite evaluations include “I learned how to sleep with my eyes open” and one student said their favorite part of his class was the view of the trees from the window. When I told people I had Father Lombardi as a professor they gasped with horror. They felt sorry for me. When other students asked why I didn’t read his ratings on Rate My Professor, I had to respond with ‘because I’m pretty sure he reads them to us.’ I had a C+ in his class which was good because it meant I was passing, but it wasn’t good enough for me. I wasn’t concerned with the grade itself as much as I was concerned with what it represented: it meant I was average. I did all of the readings for the class, I wrote in my books, marking them with post its and various colored highlighters. I switched from taking notes in pen to pencil, so I could erase my mistakes instead of scribbling them out, making my notes more legible. Simply, I wanted to do well. Partially for myself and partially to spite Father Lombardi. I wanted to show him that it was in fact possible to pass his class. I wasn’t going to be like a few of the students in my class who disappeared after the add/drop week and also halfway through the semester. I was determined to pass. I ended the class with a B, of which I was very proud. I’ve had several unpopular professors while at St. Joe’s. I’ve had students ask why on earth I’ve taken certain professors, how do I survive in this class, or isn’t that class super hard, to which I shrug and say “I passed Father Lombardi’s class, what’s so hard about this one?” There wasn’t a professor or a class on campus that could scare me after having Father Lombardi. No one was as tough as him and no class was as hard. If I didn’t have Father Lombardi freshman year, I sincerely believe the rest of my college experience would have been like a punch in the stomach—painful and unexpecting. I wouldn’t have been ready for my harder philosophy classes, my theology classes, or any class really. I was prepared to face any challenge for the remainder of my four years. I’m glad I had Father Lombardi as a professor. He wasn’t really all that scary either. In fact, by the end of the semester he made me the class grammarian, allowed me to change my allegedly permanent seat, and switch the day I took the final for his class so I wouldn’t have two finals on the same day. In my own professor evaluation of Father Lombardi, I wrote the worst thing about his class was his handwriting. I decided to talk with Father Lombardi three years later, in April 2018, and ask him if he remembered me. When I arrived at the Loyola Center, the Jesuit Residence, he said “You’ll have to pardon me, but what do you want?” He still reads his professor evaluations to his classes. He feels disappointment though because since the system switched from physical sheets of paper to online, he doesn’t get as many evaluations. He’s observed the students who hate his classes are the ones who are most likely to fill it out. I told him I took him for Moral Foundations my freshman year and I was now a senior. I reminded him during his teaching of The Light Switch Case, I was a part of the example: he electrocuted me. He laughed and said “Oh, that’s a hoot, we could have fun with that.” I asked if he remembered electrocuting me. “No.” He remembered electrocuting someone, but forgot it was me. “Actually, I don’t think I did that again,” he said. “Yes, I never did that again. I’d be creating a hostile learning environment.” “I was the only one?” “Well, the last one. What were you doing? There must have been something you did and it caught my attention during class. Were you texting?” I laughed at the idea. I couldn’t even have a pen in his class, I couldn’t imagine taking out my phone. He decided I was either very focused during class and he was trying to lighten the tension or I wasn’t paying attention at all and he was trying to get me to focus. “Where did you sit?” “By the door. We were in Merion Hall and the class was shaped like a U and I sat by the door.” “Well that’s it then.” “What’s it?” “You were sitting by the light switch.” The Light Switch Case postulates that turning on a light switch isn’t morally bad. As I later learned, the electrocution was a result of turning on the light switch, but the person turning on the light switch doesn’t know someone will die. My hypothetical death was never meant to be a result of turning on the light switch. Father Lombardi turns on the light switch with the intention to read, not to kill. As Father Lombardi said himself, “the good effect must be significant enough to compensate for the bad effect.” I had to take Philosophy 154, every student at St. Joe’s does. I didn’t have to take Father Lombardi, but I did. I didn’t have to visit him three years later, but I did. He said the visit even brightened his day. Regardless of who I took it with, I still would’ve had Moral Foundations. I could’ve gotten an A with another professor, but where’s the challenge in that? The good effect was significant enough to compensate for the bad effect.

0 Comments

CommentsYour comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed