|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

"The women in my city are my poetry gods"

By The Editors

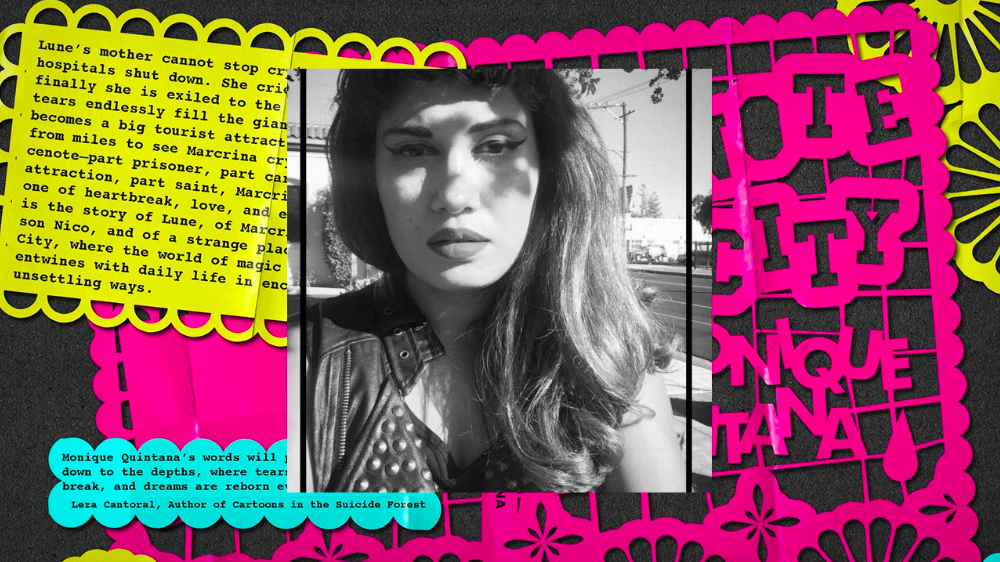

After our fiction editor Ren Martinez reviewed Monique Quintana's Cenote City, we still had so many questions! We wanted to learn more about this novella and the woman who summoned it from her imagination. So we did what nosy Quail Bell editors do: We sent an email to the author and asked if she'd agree to an interview. Luckily for us, Ms. Quintana said yes. If you haven't read Ren's review yet, start there. Then fly back to this Q&A for insight into Monique's mind, vulnerabilities, and badassery. Because when we asked her to spill, she spilled.

What's your elevator pitch for Cenote City? (Or maybe your tea party pitch. Whatever you prefer.)

Cenote City is about a brown woman/ex-hospital nurse who is inflicted with a crying curse and becomes a night-time tourist attraction in California’s Central Valley. It is a circus goth novella and novella, written entirely in the aftermath of the last presidential election. What's the origin story of Cenote City? When did you get the idea and how long before you put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard? I became connected with CLASH Books editor-in-chief, Leza Cantoral shortly after I began writing for Luna Luna Magazine. She asked me if I’d be a contributor for CLASH Media, the online magazine for CLASH Books. Reflecting on it now, writing pieces for CLASH was the first time I had fun writing in my adult life. I wrote about growing up watching slasher films in a Mexican-American family, and about why I hate the cult of Santa Claus, and I wrote a love story about brown people riding their bicycles to outer space. CLASH is invested in merging the “high” and “low” aspects of culture and making art from it. This helped me tap into a new unapologetic phase in my writing. It was liberating for me. In the summer of 2017, Leza asked me if I’d be interested in writing a La Llorona narrative for CLASH. She had dreamed up the image of a cult of women with an outrageous crying curse who flood the town they lived in. She asked me if I’d consider pitching a book project with that starting image in mind. Over the next three days, I developed a loose narrative arc for Cenote City and a list of character sketches. In writing the narrative arc, I imagined one woman being cursed and how that would impact her family and the circles of beings around her. Leza was intrigued by my pitch and so, I was, in a sense, commissioned to write the book. I began working on it that week and worked steadily for about a year before I sent Leza a solid draft. Writing the book was an unexpected blessing for me. I learned a lot about myself as a writer, and I learned a lot about the business and editorial side of writing. In my years as an MFA student at Fresno State, I had set myself up with certain ideas for how I’d publish my first book. I was certain that my first book would be my thesis manuscript. Upon graduating, I began to research the traditional route of querying agents. I also sent my manuscript to a few contests and small press reading periods, with no success in publishing it. The opportunity to write Cenote City came along and it encouraged me to take a different route. I’m glad that it’s my first book and I look forward to completing another manuscript. Writing this book gave me a whole universe I could tap into. I’m working on a collection of stories about some of the more mysterious characters in Cenote City.

What was the timeline and process of actually writing Cenote City?

I wrote about 60% of the first draft of Cenote City in the presence of my friends. For well over a year, I met up with two of my friends once a week and wrote with them. We’d always eat breakfast beforehand and write for about two hours, each of us working on a different draft. They wrote poems and I worked on Cenote City. We’d often stop and talk about what we were writing, ask each other questions, that sort of thing. Meeting up with my friends, writing the book in their presence, became a ritual for me. It’s strange because around the time I began the editing process, our schedules changed and we weren’t able to meet up very much anymore. Then began the passing back and forth of the edits with Leza, which felt like a powerful, symbiotic act. I also wrote a lot of the book in quick bursts when I was waiting for the next phase of my day to get started. I wrote the chapter, “It Seams,” while waiting to get on the plane home from AWP Tampa. I had the encouragement of my friends, my editor being one of them, all the time, whether they were physically present or not. They were like ghosts cheering me on at every point. It all felt very Mexican to me. Was that timeline and process typical for you? Do you have a set way of writing? Or do you change it up? I think my writing rituals are a byproduct of the forms I write in, or maybe it’s vice versa. I love writing flash fiction. It’ll always be my favorite form. I really believe in it. I like to see what I can write in a short amount of time, and I like to see what I can do in a small space. I think of the early drafts as fragments that I can construct and deconstruct later on, when I feel ready to commit to it and honor what’s there. Going to school for years really impacted the way I write. I’d write in small fragments at school, when I had breaks in between teaching and my classes. I’d usually be on campus from 9 o’clock in the morning until 9 o’clock at night. Then when I’d get home at night, I’d return to whatever I wrote earlier in the day. I still find myself doing the same thing. Writing fragments during the day, making sense of it at night before I go to bed. I’m sure I’ll always write this way. I approached writing the novella much of the same way I write flash fiction pieces. The structure of the narrative allowed me to have a respite in between the pieces. It was nice to have a deadline that would keep me accountable. I think the immediacy of the writing of the book leant itself to the internal conflicts on the novella and its characters. I feel like it goes at a fevered pace, or at least it felt that way the entire time I was working on it. What was it like to work with CLASH editor-in-chief Leza Cantoral? (She has such a vibrant online personality!) Leza is the kind of editor that is down for pretty much any kind of outrageousness. She wants writers to get as close to their outrageousness as possible. The thing that I appreciate most about working with Leza is that she always encouraged me to follow my instincts as a writer. I believe that there was a lot of trust involved in our working relationship. She’s now edited many of my works, not just Cenote City, but several essays and stories. She’s never changed the DNA of my writing. Her critical eye always follows my impulse as a writer and helps me to make contact with the gravity of my work. In editing Cenote City, she cut things that were bogging down the narrative. She understood the universe I was creating and helped me to bring reason and logic to it, which I think is necessary when writing fantastical work. There should be some kind of order to the disorder. Leza has a really big respect for chaos magic. I think it’s the Mexican in her. She helps to bring things in balance, whether it be the language or whatever the hell is going on with the characters. She’s a most excellent mediator. Do you want Cenote City to be seen as a Xicana or Latinx story? How do you feel about those labels in general and how do you feel about them being applied to your creative writing? When I was younger, I believed that one day I’d reach some point where I’d be an fully actualized individual, that at some point I’d have all my shit together. Of course, I was wrong about that. I’d think, once I get out of community college, it’ll all be good, and then it was, once I get done with grad school everything will fall into place, and now I’m an underemployed adjunct saying the same kind of things all over again. Sometimes I still feel as lost as I did ten years ago. But as of lately, I’ve come to honor that part of myself. I’ll call it learning. That’s what being Xicana is for me. I’ll always feel fucked in some sort of way, but I’m learning through it. If I need to cry about it, then I will. In writing this book, I’m saying that I’m learning and that I’m always going to fall short of someone else’s expectations. I’m putting that out there. I’ve spent too much of my life being embarrassed about being brown, or being ashamed about not being able to speak Spanish and apologizing to men who can’t handle my mind or the way I articulate myself. Instead of carrying that negative energy inside of me, I’ll just say that I’m still learning about my people, and I’m still learning about myself and that will come with a lot of fuck ups. I take zero issues with people calling this a Xicana book and whatever would come from that, so be it. I wrote this book as an offering to my ancestors, to my family, and to my decendents. I wrote it for my friends and for my people. If anyone puts a strike against it because they can’t appreciate that, then they’re not my people. They’re just not apart of my energy and that’s OK. What advice do you have to other Xicana or Latina writers who might be doubting themselves? If you’re writing from a place of respect, you should be proud of every single piece that you write. Even if you think it sucks at any point in time, be proud of it and own it. When you’re always proud of your work, you’ll doubt yourself less and less. For the longest time, I was worried that the writers in my city weren’t going to respect what I write and the way I write and what I write about. I had to decide not to look at what other people are doing. I just have to do my own shit and do what I’m compelled to do. Again, I think it all comes down to energy. If someone can’t respect what your doing, then they’re not part of your energy. I do believe a lot of our doubt comes to us because society sets us up to compete with each other. When we compare ourselves to other artists, the doubts creep in and deprive us of our joy. It can make us lose sight of why we started writing in the first place. I once saw a well-meaning male writer ask people to name off the top ten female writers in the city on Facebook. I found that disappointing. I see a lot of women doubt themselves when their literary communities are built upon men and gauged upon men. Heck, I do. I still go to male writers for advice all the time, and that’s something I need to work on. I see the women in my literary community resisting that. Organizing their own events and working on their own projects. The women in my city are my poetry gods. So rather than compete with women, be communal with women. Always mediate on community and think about how you can support other women in small ways. Think about it in a physical, tangible sense and in a digital sense as well. Support other women that are writing. I have been so supported by the women in my community. I could weep just thinking about it because I know it’s real. Read their work and share it if you have the time and inclination to do so. Use social media to encourage other women. Community helps to alleviate the doubts that we have in ourselves and the work that we do.

0 Comments

CommentsYour comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed