|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

Interview: David Coogan and Stanley Craddock, Authors of Writing Our Way Out: Memoirs from Jail7/30/2019

Open Minds Lead to Freedom

By Rachel Rivenbark

Dr. David Coogan is an English professor at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia, largely specializing in both rhetoric (the study of argument, and how it is formed) and the topic of social change. He has been teaching at VCU for more than ten years, and just this last Spring, I had the distinct advantage of being able to take his Introduction to Modern Rhetoric course at the university, which allowed myself and the rest of the class to engage in an ongoing, semester-long debate about issues such as race, gender, sexuality, class, and many others.

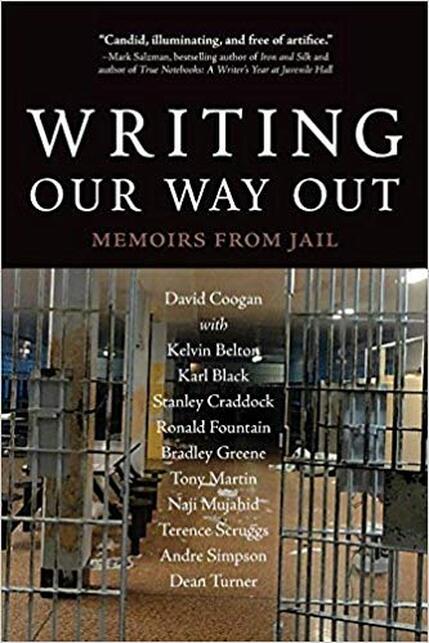

In 2016, Dr. Coogan - in association with Richmond’s own Brandylane Publishing - published Writing Our Way Out: Memoirs From Jail, a vivid, emotional, and highly enthralling collection of memoirs written by ten men incarcerated in the Virginia prison system, detailing their life stories and the circumstances which led to their incarceration. These men included Kelvin Belton, Karl Black, Stanley Craddock, Ronald Fountain, Bradley Greene, Tony Martin, Naji Mujahid, Terence Scruggs, Andre Simpson, and Dean Turner, all of whom formed a significant and lasting relationship of trust and respect with Dr. Coogan throughout the years he worked with them to write this book. Early last week, Dr. Coogan and his good friend and co-author Mr. Craddock both agreed to meet with me at Mr. Craddock’s place of employment, for the sake of conducting an interview about their involvement in the process of creating Writing Our Way Out.

First of all, it genuinely is an honor to meet you, Mr. Craddock. I really have to say that your sections of the book were some of my favorites, and they honestly drove me to tears more than once. As Dr. Coogan knows, right from the introduction to your memoir, I became very invested in the progression your story, in particular. Now, you’re here, you’ve got a steady job, you’re looking good, but I still have to ask, you know - how are things going? How are you doing?

Craddock: Uh, you know… I was watching The Price Is Right. And towards the end of every segment, all the winners get an opportunity to go to the wheel. And they have to spin the wheel, right, and they want to get a dollar. Because if they get a dollar, there’s some bonuses on getting a dollar. Some people do, some people do… the reason why I’m saying that is because I’ve stepped up to the wheel. You know, I’ve stepped up to responsibility. And I spin it, right, and I don’t always get a dollar. [He laughs] Sometimes I get a nickel. But I get to spin again. And every day out in society is an opportunity for me to spin, to make a right choice. That’s great, that’s absolutely wonderful. And I have to say, your - frankly, gorgeous - endnote in the book aside, your memoir ended at a point where you were still incarcerated and awaiting release. For many of the other men involved in this project, readers were given a glimpse into what the process of re-entering society was like for them, at the time of their release. If you don’t mind my asking, what was this process like for you? Craddock: It was, uh… it’s not complete, it’s still difficult. It’s still difficult. Every day. You know, I have some remnants of institutionalization. And I know it. Of all the times that I felt comfortable being released, it’s when I went back into the prison. I felt… I felt comfortable. In prison. And you know, in some ways, I wish that I could create my own incarceration. Where I could live in prison, and go to work out in society, and then just at the end of my day go back to my cell. Would you say that stems from a sense of familiarity with it, or…? Craddock: [Brief pause] So much of my emotional system is connected to those places in life that are hidden from people. So I guess in some sense, we all have prisons, some cells we stay in, you know? Um, re-entry… re-entry means resocialization. Who’s gonna help you to resocialize? You know there’s really no programs out there that actually help you to resocialize back into society. There’s a plethora of programs, right, that say that this is what they specialize in. They specialize in housing. But that’s not resocialization. They specialize in job placement. But that’s not resocialization. Resocialization is an emotional thing, you know? You can get the job, you can get the vehicle, you can get the girl, right? But you’re still mangled. Your emotions are still mangled, there’s parts that you just haven’t quite unknotted it yet, you know? Uh… sometimes my emotions are very convoluted. I just… I just don’t understand, at times. But am I being resocialized? [He laughs] I think what I’ve learned to do is to contort myself to the environment that I need to be in, and I’ve learned how to put a personality on, just like all these suits. That’s… really very insightful for you to say. And I’m really, honestly glad that you’re doing so well, and that you’re starting to reach the point where - where you can feel you’re maybe starting to get there? Craddock: People assume that you’re there. And they don’t understand. They don’t understand your issues. You know, if you’re a parent, no one knows your household like you know your household. You know, when people come in, they don’t see your household, they see what you present. This was honestly an extremely enlightening and very, very heart-wrenching book to read, across all the memoirs, but - this one is for you, Dr. Coogan - I have to say, it’s a very niche sort of topic. And it’s not, if you’ll excuse me saying so, the kind of subject that your average white male author would seek to engage with. So I’m wondering, what first motivated you to start doing these workshops, that first began with inner-city children and eventually grew to the basis of this book? Dr. Coogan: Well, I’m an inquisitive person. I like to get to the bottom of things. And I also have a lot of faith in people. I believe people pretty much already have what they need to be creative and intelligent and to write and to figure out their own solutions to their problems. The fact that Stan can describe what he just did is proof of that. That he knows, “I’m connected emotionally to prison, I know that sometimes I wish I could be there, but I know I can’t,” that’s he’s putting all that together, and he has been for years, is proof of that. That all the other men in the book - and the ones who didn’t make it into the book - are proof of that. So I was motivated by my desire to see, I guess, if I could help people figure out the answers to their own questions, and also just to be vindicated that humanity is alive and well, despite what we hear about criminals, and the prison system. That good things can happen, that we can triumph, we can overcome, that we can at least try to triumph and overcome. So I didn’t go with answers, I didn’t go with political convictions other than that community is desirable, and the more diverse, the better, and when people are helping each other frame questions and find solutions about the difficult problems in life - including racism, addiction, poverty, health, mental health, all those issues - when people do that together, the burden is lighter, and the solutions are easier to grasp. When they do it alone, it’s harder, because it becomes like a big sack on your shoulders. And you think you’re strong, but then you become like one of those weight lifters like, “Just look at me, I can move it up over my head! Look at me, I can move it around this way! Look at me, I can add another plate on it! I can move-” You know, good for you, you’re strong, you’re holding it in. Why don’t you let somebody help you? You know, so it’s... I learned just as much as I think Stan and the rest of our coauthors learned, and I’m grateful for that, I’m grateful for the opportunity that they shouldered some of my burden. You know? Listening to me talk about rhetoric. [Stan laughs] Listening to me talk about literature. They’d listen to me and then ask me, “Well, what do you really mean?” And I love that, because what that tells me - or what it’s told me over the years - is that they care enough about me to communicate with me and to really get to the bottom of it, right? And that’s honest, and that’s why we’ve become such good friends, you know through this project as it’s gone through the different phases. So I think I’ve always been that way, even before I moved to Richmond, you know, just the way I am in the world, in my other job, and in my life, as a student and in high school. I think I’ve always been that way, but moving to Richmond and being confronted with that crime scene that I described in the beginning of the book, and just kind of taking stock of my life, and realizing, “Well, here I’m about to start this new job - what good is that, in relation to this?” You know, like it bothered me that I had the luxury of walking away from that. I didn’t have to pay attention to that at all. I could just go on, and it bothers me that the academic life encourages that. You can be a successful academic - well actually, any professional life, you can really just be separate from the problems confronting everyday people. And so my desire was to get closer, not just personally, not just through issues like race or mass incarceration, but also professionally, I wanted to see if I could turn the face of this university a little bit towards this jail; they’re only three miles apart. And that was the main motivation, yeah. You’ve most certainly done it professionally, and you’ve certainly done it as an author as well - do you feel you’ve done so personally, in terms of how you now view the world? Dr. Coogan: Absolutely, and I still learn. I, you know… [He laughs] The other day... let’s see if Stan remembers this, it was actually a couple months ago, we were having a conversation over the phone, and I was saying something along the lines of, “But is that what you always wanted to do in life, or where do you think you belong? You know, what’s your calling?” and all that, and he interrupted me and said, “Man, that’s what white people think!” Craddock: I remember that conversation. Dr. Coogan: And what he meant was like, you’re talking as if you’re talking to somebody who has all this freedom and privilege and resources and opportunity, and he basically reminded me what it’s like to re-enter society. You’re not asking these big questions about your calling in life, and what you’re comfortable with. Like he said, you contort yourself into the situation to survive. And I think a lot of people of relative privilege - and for me, that comes through whiteness, at least half the time it does - but however you want to say it, people who don’t have to struggle that way, it’s good to be reminded by your friends what the struggle in life is like for them. ‘Cause it gets you out of yourself, you know, and it gives you a new way of thinking about justice, and what you can do, so yeah, that stuff’s affected me personally. So, obviously these are some extremely emotional, very raw, very agonizingly human stories that you’ve tried to help tell, here… what part of doing this project, and being involved in this process stuck out the most to the both of you, or affected you the most significantly? And were you surprised by it? Craddock: It wasn’t writing. It wasn’t writing… it was the relationship. The writing didn’t change my mind. It just showed me my mind. The relationship with Dave is actually what ignited, and fuelled the change. I care about Dave. So I value his opinion. I value whether… I never had anybody that I had to be accountable to, you know? Not no white cat. [Coogan laughs] And I value Dave. And Dave talks to me, even when I was wrong about some stuff, he was mad with me, and I felt that. And I had remorse. Not for what I did, but for who I hurt. With my selfish, criminal mindset - it’s easy for me to disconnect myself from the crime, but it’s difficult to disconnect yourself from people that you care about. I think it was Dave, and I think Kelvin, Dean, Terence… I think the writing was the key that brought Dave into our lives, right? But it was the friendship that kept him there. Are you surprised now, or were you surprised at the time, of just how significant your relationship to Dr. Coogan wound up becoming, just out of this one course you elected to take there? Craddock: Sure I was surprised, because I was on my way to prison. And it’s interesting, right, because you know when you go down to Richmond City Jail, you go through the quartermaster, you gotta take everything off. You’ve gotta leave all your personal belongings somewhere else. And when you go to prison, when they call your name, and you have to get on that bus, there’s things you just leave. You just leave, and I went to Greeneville, and I was like, “What am I leaving? What am I gonna leave?” And you know, some of the other institutions I left, you know that I went to, I didn’t take my emotions. I didn’t. But after this course, I took my emotions. Uh… and in prison, right, you see and you don’t see. Doesn’t matter what your perspective is, it doesn’t matter your position, what’s morally the high ground, because that’s not the safe ground. You know? And after taking this course, I found myself analyzing what I thought, and how I felt. And at times, I shared it. With the particular situation, it made me uncomfortable, it put me in harm’s way, but I was in harm’s way anyway. So… it was the relationship with Dave. It was that butter bread, and- Dr. Coogan: Banana bread. Craddock: Yeah, banana bread! [They joke around for a moment, both laughing.] And you, Dr. Coogan? Dr. Coogan: I forgot what the question was. That’s okay! It was basically, what stuck out the most to you about the whole process, or affected you the most, and were you surprised by it? Dr. Coogan: Ah, um… Wow, there’s a lot of things that stood out for me. I think that the first thing that really surprised me was how seriously all of the men took the invitation to write. Now, not every single one of them, because you see ten men in the book, and there were dozens of others who took it seriously for a little while, but chose not to publish, and there was a whole bunch of others who didn’t take it as seriously. But overall, I was surprised both by the fact that this invitation by a stranger to their world, who’d never been to prison, doesn’t look like them, you know, doesn’t sound like them, that they would take that seriously. And second, that so many of them would be so insightful, and talented. I kind of suspected both those things would happen, that was sort of my theory going into it, that there’s nothing wrong with these people at all. They’re intelligent, they’re creative, they’re fine as they are, but they’ve been denied opportunities, and they’ve struggled in ways that I can’t imagine, so let me go and figure out if I can help them as a writing teacher, to figure that out. That’s what I theorized, and that’s what I discovered when I came in. But to think it is one thing, and to experience it is another, and when you have men like Stan saying, “I really wanna stick with this course, even though I’m going to prison,” and it wasn’t just a semester course, it was like - it was about nine months at the jail, and then it was years after that, and letters in prison. And the fact that he, Naji, Dean, and the others would do that, open up their lives to me, and do it so insightfully and creatively, and stick with the process for years, that really overwhelmed me, in a good way. Because like I say, it was an inquiry into life together, and I didn’t come with answers, I didn’t go on a charity mission, I didn’t go to prove a point politically, I didn’t go to do scholarship, really; I went as a teacher and as a citizen and as a man. And then, when we decided to write, we weren’t going to make a book like this. That kind of developed in the conversation, and I realized that they were good enough to actually pull off the writing. I just now had to figure out a way to make it a book, and I wasn’t going to write anything, I just thought they were doing all the heroic work, and like any writing teacher, you don’t hold the pen of the student, or put your hands on their keyboard. The writing teacher’s job is to kind of sidle up on the side of the writer and kind of look at the page, with her or him, and just ask questions and figure out, “Well, what’s that? What’s that going on there?” And listen more than talk. Right? You were in my writing class. Yes! Dr. Coogan: That’s how I see the job, but this is not college class with credits and grades, this is - we’re doing this as adults, of our free will, in a situation that’s difficult. Hard to get in, hard for me to stay there, and to have a secure place to work, because nothing is stable in prison. So you know, a teacher is kind of used to class starting on time, ending on time, same people always there. You know, none of that’s the same, so you depend upon guides - you know, it’s not my world, and so Stan and Andre and the rest became my guides, they understood that I didn’t know how to really be there. Although I knew writing, and teaching, they made it comfortable for me to open up as a teacher more, and so that really surprised me too, that I could become a better teacher and a better person in their company. I kind of knew that I would learn something, but I didn’t realize how much, how profoundly it would impact me. That actually serves as a very good segue into my next question. Where… you mentioned multiple times throughout the book that a number of unmotivated students and administrative problems in the prison system were particularly large hindrances in the process of trying to put together each man’s memoir, but were there any other significant stumbling blocks which either you or your students had to overcome in order to get this book finished and into the hands of readers? Dr. Coogan: Well, the stumbling blocks in the jail were the things that we’ve just mentioned, you know… predictable class times - contact hours, you would call it, basically… and then, you know, everybody getting sent off to different prisons. You know, there’s nothing about mass incarceration that’s set up for education. Nothing. You know, it’s all about their property, their - Craddock: Security. Dr. Coogan: - dispersed - yeah! And so they’re… when you look at someone and say, “You’re not a prisoner, you’re a student,” you’re suddenly transforming them in your eyes into an agent, an intellectual person, a creative person, a free person. And the environment that you’re in is saying the opposite all the time. So that was one kind of issue I had to contend with. To the point about getting the book published, my first concern about that was, are they saying anything that would either hurt themselves and their cases? Or anything that would jeopardize our project itself? Or our ability to kind of, like… when people publish memoirs, especially in difficult situations, whether it’s a warzone or a prison, you know… lawsuits can arise when people are mentioned in the books that are angry about the way they were portrayed, or you talk about a prison system, so… I was wondering about that. But we had never set out to talk about specific crimes, or about prison politics, so I more or less got over that concern that the book itself would open us up to become targets for something. But getting the book published itself, that was actually much more of a compelling problem. Just the process, because I had a steep learning curve. I’m an academic, used to publishing in journals and with academic book publishers, and that world is very straightforward. You know which discipline you’re in, you know what topics count, what methodologies you use, and you know who the editors are, and how to get it in. Commercial publishing is more like Hollywood or the music industry, there’s nothing rational about it. It’s like, who you know and who’s your agent, and all that, and that process kind of bothered me, and it took me a good couple years of learning it to understand two things that should have been obvious from the beginning, but I just needed to learn it my way. Remember I said earlier, I wasn’t gonna write anything? Well, that’s how the book was at first, it was chapter length memoirs from each of these men, with a very short introduction from me. And nobody wanted to publish that. And Stan and Kelvin and the rest, one by one in their own ways, told me “You need to write more.” Craddock: It’s about you. Dr. Coogan: Yeah, he said, I think Stan was one of the first to say, “I think our stories are okay, but it’s your curiosity about our stories that’s gonna make it a book.” So in other words, what I wasn’t telling was the story of the process of how we got together. It’s like, a photograph that zooms in right onto the cool waterfall, but you don’t see the rocks around the waterfall, like the path, and how do you get there, you know… I wasn’t telling the whole story there, so because they challenged me, I did it. I wrote a draft of my section, so that took a little more time. And the first insight I got from that was that I did have a story, and I didn’t think I did. The second one - which also should’ve been obvious - was people don’t care about an anthology of prisoner’s memoirs, just like they don’t care about prisoners. I mean, why do we have over 2.2 million in our prisons today, except for the fact that it’s easy to not care about our fellow human beings? And so, when I was trying to ask publishers - again, people of privilege - to “look at these men, look at what they’ve done,” their reaction was, “Why should I care?” And so, I had to use myself as a character, and part of that is my middle class, white kind of identity, but the other part is just the professor searching for an answer. You know, the inquiry. I had to use that to write my story, so I could be like the lens through which people can see people; they can see Stan, and Kelvin, and Naji, and the rest. And I was uncomfortable with that at first, because I didn’t want to take away from their own ability to tell their own stories. I was uncomfortable at first with editing some of their writing, for the same reason. Basically, both of those things forced me to become a filter, but then I learned to embrace it. I realized that, again, I have a story, which means I did something, I got into this jail, and I found a community with these writers, and together we accomplished something, and it’s my responsibility to share that now. So I kind of let go of some of the guilt or misgivings. Because you know, right down from the way we made up the story, to the way we made the contract, we were very upfront, very transparent that I’m not taking this from you, we are sharing this, and then that it’s not a big money making book to begin with. [He laughs] But we were clear about that, that we’re not doing this to make money. You’re gonna read the thing, you’re gonna give your approval. It’s everybody equal. So yeah, confronting the publishing world with this kind of thing was awkward, and a little annoying at first, but honestly, I don’t think I could’ve done it if they hadn’t encouraged me to write it, and trusted me for the years it took to finally resolve all that. And, I have to say, from a reader's perspective, those extra inclusions really did do a lot to build intrigue for the memoirs, because one thing that really struck me, particularly early on was that much like you didn’t want to come into the prison knowing what crimes the men had committed, their backgrounds, any of that, I was very much struck by the mystery in that readers are also left to wonder about these men who are brought forward as prisoners in the introduction, and in these behind-the-scenes sections. And along similar notes, I also have to say that something that very much built up surprise and intrigue for me in the book, was that... I didn’t realize up until the very ending that Andre was killed in the car crash that was mentioned in the introduction to the book. Dr. Coogan: Ah, okay… yeah. Yeah. Interviewer: And I have to wonder, was that an intentional choice on your part to leave that sort of vague in the introduction, so that readers wouldn’t realize that was how the situation had ended, until they had seen who he was, and until they had gotten emotionally invested in him and his story? Dr. Coogan: Yeah, I… I can’t remember who clued me into that, but I think it was one of my colleagues in creative writing who read an earlier draft. Plotting is hard, you know? And again, academic - I write arguments, but learning how to write…? Plotting succeeds by withholding information. You deliberately wait to tell, and then which information do you withhold, and why? That depends on the kind of story you want to tell. So you’re not manipulating, what you’re doing is withholding until the right time, when you think the reader can get the revelation. And so, by framing the book that way, where I’m talking with Kelvin, Andre’s been in this accident, I wanted the focus to be on the questions that we were asking over the phone - why would he do it? Why would he go down this path again? And the way that prologue is set up, it ends where Kelvin says, “Dave, you’re the only one asking questions like this.” Right? And that sort of forces you to think, “Why is he asking questions like that? And what are the answers going to be?” And then hopefully, the book works that way, when you go through each chapter of my journey into the class, and then the men’s journeys into their own lives, you understand that the reasons why people head into the criminal justice system are as complex as the humans writing the stories. So there’s no one answer, so you need the whole space of a book to get through the answers. You look at the back of the book and you see a couple of white guys, and majority African Americans, but just because you see that, doesn’t tell you what white is or what black is. You’ve gotta read the stories, because they’re all very different. So yeah, uh… Andre dying… was a really difficult thing for me, because it meant I had to confront, uh… something I really didn’t want to confront. And that was, “Is it possible that you can’t write your way out? And you’ll die trying.” And, you know… I haven’t been around a whole lot of death, I don’t take it lightly, I think that if you ask someone to try something, and they die trying to do it... I felt responsible. Then I had to realize, I’m not responsible. I just became a part of his story. And I had to kind of deal with the tragedy the way anybody in his family might. And I cried, and I was scared. I was hurt, I felt betrayed. But I had to process through all of that. Because if I held it in as a guilt, or as a problem, then it would be real. And so, what I did was I talked to everybody, I wrote about it, and when I was putting the book together, I realized that, you know… memoirs start with the beginning of life, and then they tell of a very memorable time in life, that was difficult or sad or tragic, and these memoirs are mostly focused on prison as the ultimate - you know, that’s like the third act of the book, when they’re coming to that realization of who they are, in prison. But life is bigger than a book, you know? Your memoir starts with your first memories, as a child, but your life ends when your life ends. And so, I realized that Andre’s death symbolized something much more, you know… kind of profound, to me at least, about this process that your effort to figure out who you are, and where you should be, and what you should be doing in life, doesn’t end until you’re unable to try anymore. And he was trying. And it was a relapse, not unlike other relapses from some of the other co-authors. It just ended the way it did, and that ended the inquiry. There’s no more searching for him. But I can keep going. And that moment in particular - especially after spending the whole book hearing his story, and getting a feel for him as a prisoner and as a human - I really have to say it was extremely jarring to go through the whole book thinking, “Oh, well, he had this relapse, he got arrested, but… we’re probably going to have a happy ending at the resolution,” and I have to say, getting to the end and having that revelation after everything, made it like a sucker punch to the gut. It was so painful, I cried. Dr. Coogan: Yeah. Now you know how I felt. Mhm… and I think that was a brilliant move with the book, because it really makes it sink in to readers just... the tragedy of it all. It brought it home, in a very striking way. Craddock: You know what I like about it? And I remember when Dave was sharing with me, right? You know, when he was going through the grieving process. I said, “Dave, man, you did something right, that is great. You actually gave him a choice.” See, I would be disappointed if I didn’t have a choice, you know, and I had to die. When I don’t have a choice. And Dave gave Andre - as well as myself, and all the other guys that are in the book - a choice. And that’s all you can give a person. And whatever you choose, his choice brought life to his death. It didn’t have to. And I told Dave that he oughta applaud himself, that he was given the opportunity to give a choice. That’s what he gave me. A choice. And then that had given life to me taking responsibility of my own life, and understanding that I always have a choice. At first, I didn’t. Education gives you a choice. If I remember that vampire movie, uh… Brad Pitt was in, with the Interview With a Vampire. He didn’t want to be a vampire. He didn’t want to bite people. He didn’t want to kill people, right? But yet, he was a vampire. So he was sucking the blood of rats. And how do I connect this? I know who I am. But I don’t have to suck the blood of rats. I’ve accepted the fact that I do go hard. I will go hard, right? But I don’t have to go hard. I accepted the fact that I am an aggressive Black male in society. But who made me aggressive? Society made me aggressive, and my parents had to reinforce that, in order for me to be prepared to deal with society. They had to reinforce that. I couldn’t come out the house the way Dave came out of his house. We lived in two different jungles, you know. His was a park. Mine was a jungle. His got trees, mine’s got trees, but I got some shit lurking around in mine that’s not safe. So you have to learn how to deal with your social circle, in order to step out of it, into another circle. And I still live in a drug-infested neighborhood. Dr. Coogan: [He turns to me] Does he seem like an aggressive Black man, to you? Definitely not. Dr. Coogan: So that means he’s exercising his choice. So he’s not only that. He can be, he can contort himself into that, and has, but he chooses not to. Craddock: I live in Church Hill, Dave lives in Church Hill. Two different parts of Church Hill, though. Dr. Coogan: Very different. Craddock: Same area, though. And there’s times that when I walk through - you know, I had a guy tell me he was gonna shoot me, he had a gun in the bag, you know? And what I did was revert right back to being aggressive - I said, “You’ve got a gun in the bag?” He said, “Yeah, yeah.” So what I did was confront him, I walked up to him, because you’re not going in that bag. If that’s where you say the danger is, that’s where my problem is, is that bag you’re going in. Then that’s not a problem. That’s not a problem. You’re not going in that bag. You know, and… the choice that I had was to step up and be aggressive, right? He didn’t know that I had twenty years in prison behind me. He didn’t know that. And I didn’t tell him. And I didn’t show him. What I did was understand how to de-escalate it. Prior to that, right, I would’ve just went on and just ran him over. I’d have just run him over. Because that’s the norm. You say you’re gonna hurt me - okay, I’m gonna hurt you. Then when you go to the judicial system, the judicial system don’t understand that you’re judging me, you’re trying me on a law, but it does not fit today’s time. You know, when a person threatens you, I’ll believe you. It’s just different. Dr. Coogan: It goes the other way, too. Me reacting the way I did to Andre dying is not the same way Kelvin and the others reacted, because they’re used to that. And it’s happened with people much closer to them in their own lives. Where they were the ones being threatened, like he just described, and they could’ve died. [A brief interruption occurs with a customer arriving in the shop to inquire about having a jacket tailored. Dr. Coogan and I pause the interview until Mr. Craddock has seen the customer out and returned.] Dr. Coogan: Just to finish the thought, what they pointed out to me - and they did this multiple times, even before Andre died - was my caring about all this was a shock for them, because it’d become routine. Death is routine. Having your security compromised is routine. Not having choices is routine. Being told you don’t have a future is routine. And every time I heard that it’s just normal, it shocked me, because the more times it happened, the more attached I am to all of their welfare. And it happened like when people would get shipped away from the jail to prison, and then the scene you’re talking about when Andre died, that happened with other people we know, too… it’s like, every time it gets worse like that, I realize I’m in it now. I care. And it shouldn’t be normal, what they’re experiencing as normal. It shouldn’t, it’s not right. Craddock: When you were saying that - you know, I’m gonna speak in layman’s terms - I was thinking about a parable that’s in the Scriptures, right? About this sower. And you’re out sowing, but you’ve got to understand if you’re going to plant some grass, not all grass grows. Not every seed produces a blade of grass. It says that some fell on the rocks, some fell on the sand, and some fell on good soil. As much as you would - our world would be utopia if everything was just as simple. But there’s no such thing as Utopia. There are some collateral damages. There are some friendly fire situations. There are some casualties to change. Dr. Coogan: We don’t have a Utopia.. That’s not the world God made. Craddock: That’s not the world. Dr. Coogan: I mean, there’s differences… there’s adversities, there’s injustice, there always has been, and probably always will. I don’t think we get to a place where we end all of that, but I do think we can increase our capacity to care about ending it. You know, if we can all want the same things- Craddock: I think we’ve gotta start by all seeing it, and recognizing it. Dr. Coogan: See it, just to acknowledge it. Craddock: Just to acknowledge it, right. Because it’s Bryan Stevenson who said that if you change your proximity, it’ll change the narrative. So you’ve got to see it, you’ve got to see it and then you have to make a choice to move closer to the problem, before you can reach the solution. You have leaders, they see it, but they don’t move closer to it. Dr. Coogan: They don’t move, yeah. Craddock: So how can you expect to change the narrative of it? My idea of the actual maturity of Writing Your Way Out - and I’ve told Dave this - is I would love for Dave to meet the young lady that got raped in Libby. Because she’s the actual seed. That’s how this whole process started, right? And it would just be a great gift in the midst of her quagmire, to say, “Hey listen, this is what you inadvertently started.” You know? Dr. Coogan: Yes, that’s an interesting idea… I don’t even know her name. Craddock: I know. Dr. Coogan: I don’t even know the names of the four boys, either. Craddock: I know. Dr. Coogan: We never learned them… because the growth of that story was enough for me. I wasn’t about the facts, and I didn’t want to, like… pull anybody into some kind of like- Craddock: I get it, I truly get it, but you know... I watched - this is how institutionalized I am - I watched a prison movie last night. Dr. Coogan: [Laughs] Which one? Craddock: Uh… O.G. Dr. Coogan: Oh, okay. Original Gangster. Craddock: Original Gangster. And uh… and the young lady looked beautiful, I could’ve been watching her, right? But I needed to go back to prison. Dr. Coogan: Yeah. Craddock: Only for a moment. I do need to go back to prison… but only for moments. Not years. Not years. I don’t belong, and I belong… what do you call that? Ambivalence? Dr. Coogan: [Laughs] Yeah, ambivalence. Craddock: Yeah, ambivalence… two different - one particular thing, two different thoughts, right? And that’s my balance, in there. The judge... I ain’t tripping off - hey listen, I ain’t tripping off none of them judges, I can do whatever the hell I want to do at any time. Because I realize they don’t have any authority over me. They sell you on the idea that they do, but they don’t. I’m just as sovereign. [Laughs] … sovereignty. Dr. Coogan: [Laughs] Yeah, you’re sovereign. Craddock: Yeah! But I don’t tell them that. I allow them to have what they think, but in the end, I’m gonna do what I wanna do. I want to live in Richmond, Virginia, I want to work at Stockpile, I want to go see Alan, have ham biscuits- Dr. Coogan: Down the road. Craddock: [Laughs] Yeah, I wanna go drink a couple brews, and listen to my buddy playing music, right. Dr. Coogan: We’re gonna like that. Craddock: Yeah, we’re gonna love it! And I don’t want to go to commisary no more. You know? I don’t want to be strip searched no more. I don’t wanna squat and cough no more. I don’t wanna do all that. And that’s sovereignty in me, it’s my choice. And that’s what I choose. Dr. Coogan: [Turns to me] I have to leave in about ten minutes, so do you have any more questions you need to ask? Because we can just keep talking. One question we'll talk for a couple of hours. We’ve done it before. [He and Stan laugh] Yes! Reading this book, I was very much struck by just how stunningly beautiful some of the writing was - particularly by men who largely claimed little or no experience in writing - and the skill with which they managed to tell their life stories. To your knowledge, have any of them - yourself included, Mr. Craddock - pursued any further kind of writing, either of a biographical nature or not? Craddock: Yes. [He grabs the notebook beside him, and flips through it] I write a whole lot, you know… Dave got me in a whole lot of trouble with that, right. Because when I was in prison, guys would hire me - [Coogan Laughs] - to be the gunman, to go against administration. And I’ve learned the power of writing. I’ve learned it. And it’s wonderful, right, because if you look at the Qur’an and you look at the Bible, right, and after we’re gone, we’d better put our thoughts down somewhere, so that way they can be etched into the minds of our children, or to the hearts of society. You know, Martin Luther King wrote something, “I Have A Dream,” and we still recite it... Even Bart Simpson says some old slick shit sometimes. [He and Coogan laugh] So writing, it’s actually just communicating. Dr. Coogan: Dean is writing children’s books, they’re not published yet, but he’s drafted a bunch of them. And similar fictional urban lit. Ronald is writing kind of like the next chapter of his memoir, it helps him - it’s sort of like journal writing with a forward look, he’s kind of trying to keep himself moving into that next better phase. For a while, Naji tried writing journalism, you know, like to see if it might be a career, but it was too much of a hard transition from a regular working life to doing that for money. So.. by and large I don’t think everybody is doing the same thing, or writing memoir, but here and there, they’re writing it. And I’m sure readers are also very much eager to know what lies ahead for you as well, Dr. Coogan, as both a teacher and as an author, and I was wondering, are there any projects in the works that you would like to give an insight on? Dr. Coogan: Sure, I was writing all day today, and the day before, and the day before that… I’m finishing up an essay about the rhetoric of redemption in prison memoirs, and so I’ve read a whole bunch of contemporary prison memoirs, and I’ve got my theory as to how the narrators tell their story of overcoming difficult life experiences and redeeming. We’ve got actually several essays on that, ones that we’re finishing now… but my next big writing project is a sequel to Writing Our Way Out, that I’ve been thinking about for a long time, and in my own way, drafting and sharing. I just didn’t quite realize it. I get asked a lot by other teachers and other writers, how can I do what you did, in this book? So I started doing some teacher workshops on this method of organizing your class, teaching it, and judging what you’ve done, in jails and prisons, with at-risk kids and all… and just anybody else, like Stan said a minute ago, who’s stuck in their own prison of their mind. So I’ve been imagining and sort of sketching out a new book called Writing Your Way Out that’s gonna help people do exactly that, for writers who are on their own, who maybe they read this first book, maybe not, but they want a way of applying this method that we’ve developed. But it’s also gonna be of interest to teachers who want to teach that kind of class. So that’s the next big one. That’s brilliant, I very much look forward to it! That was about all the questions that I had, so I’d just like to leave off on, do either of you have any final words or insights about this book, or your work, or your associates in the project, or anything else, that you would like to share with our readers at Quail Bell? Craddock: Yes. I heard someone say that wise words grow older. And I would hope that through the readers and the audience that have an opportunity to put Writing Your Way Out into their hands, that our words would grow older. Dr. Coogan: Yeah… I echo that. I think that this is a hopeful book, that teaches people that change is possible, if you humble yourself before the mysteries of change. And just stay patient, and apply yourself diligently, just show up faithfully, and try to imagine a better life. And that’s what we did, that’s what every man in that book did, and that’s what we’re continuing to do. And it’s something that I think we’ve learned just from the many events we’ve done, listening to people who asked their questions and shared their stories, it’s something that a lot of people are finding out that they can do, and that they probably should be doing more rigorously. Anybody can write their way out, if they really try, and if they have a community to help support. Great, well, thank you so very much for your time, and for sitting down with me to do this interview. I look forward to seeing what comes forth from the both of you! Craddock: Well, we look forward to seeing your writing! Thank you. Dr. Coogan: Staring with this interview. Craddock: Starting with this interview, yeah! [They laugh] _______________________________________________________ For more information on Dr. Coogan, please visit his faculty page at Virginia Commonwealth University, here: https://english.vcu.edu/people/faculty/coogan.html To find out where you can order your own copy of Writing Our Way Out, or for more information about the book or publisher, please visit the book’s listing through Brandylane Publishers, here: https://brandylanepublishers.com/wp/book/list-all/memoirautobiography/writing-our-way-out-by-david-coogan/ For more information about the non-profit Offender Aid and Restoration (OAR) program which first encouraged Dr. Coogan to form the class that would evetually make this book, please visit their website, here: https://www.oarric.org/ And finally, for more information on VCU’s Open Minds program through which Dr. Coogan works to help students and prisoners alike take enriching service-learning courses, please visit their website, here: https://openminds.vcu.edu/ Comments

Marty Cosgrove

7/30/2019 01:56:16 pm

Fantastic interview/article. Thank you Rachel, Dave, and Stanley. It's refreshing to read such deep and heartfelt material when surrounded by the news of the day, which is usually anything but. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed