|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

Essay: The Past, Present, and Future in Lebanon's Beit Beirut Museum and Urban Cultural Center2/13/2019 A Tribute to 7,000 Years of History

By Melina Bee

The museum and urban cultural center Beit Beirut merges pre- and post-war Lebanon to create a healing space. The building once occupied the physical border between warring factions to the east and west. Now it occupies the emotional border between a painful history and the promise of a better future.

The museum's exhibits, as well as the building itself, stand as a testament to a resilient country and people still reconciling loss and hope. Beit Beirut currently showcases the remnants of a photo studio it once housed, as well as modern photos which capture the reality of child labor. When he designed the building in 1924, architect Youssef Aftmus could never have imagined the horrors that would later take place here. Originally named Beit Barakat after the family who commissioned it, the building quickly earned the enduring nickname of “the yellow house” due to its sandstone facade. The spacious, airy layout, and prime location were a major draw for middle class families and ground floor shops. Tragically, these same features would attract danger and violence during the Lebanese Civil War.

Before 1975, Beirut was considered the “Paris of the East” but that reputation quickly changed at the outbreak of one of the most infamous civil conflicts of the 20th century. By the time the fighting ended in 1990, approximately 120,000 people died, 76,000 were displaced and one million fled. Beit Beirut’s residents as well as the building itself are among these victims of war.

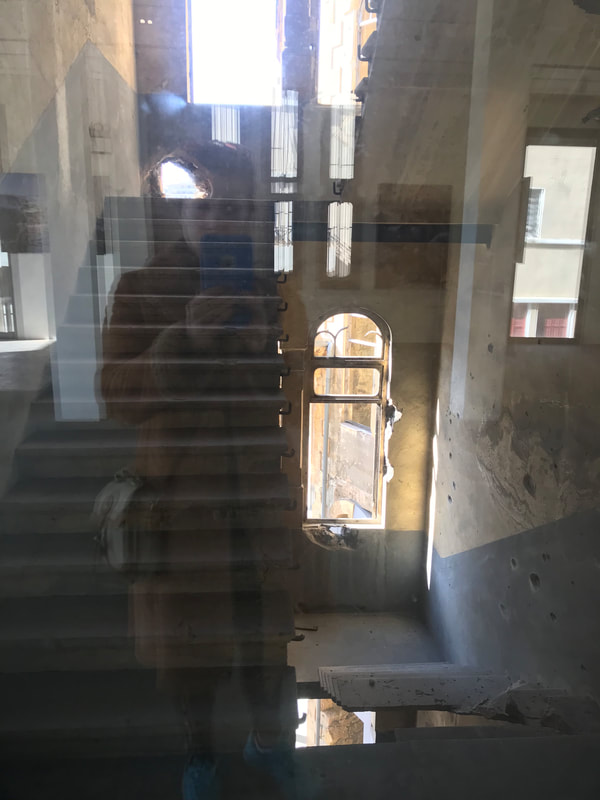

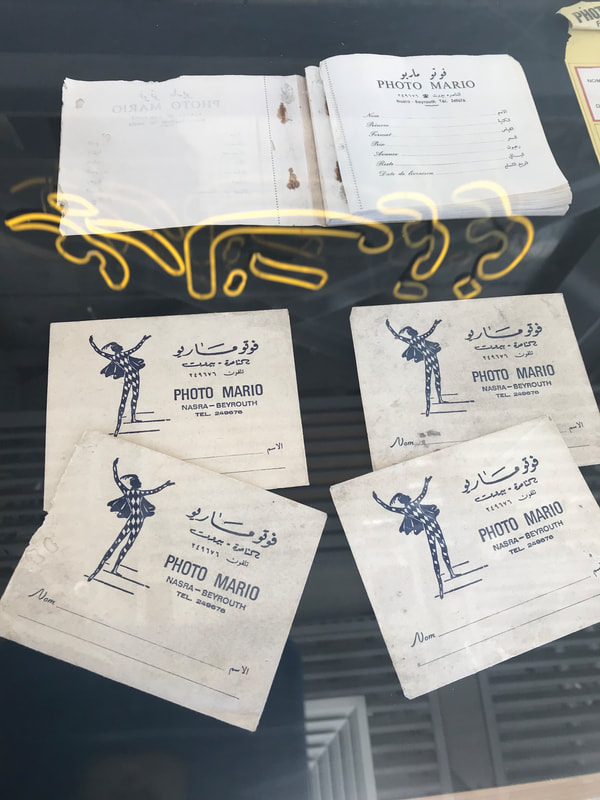

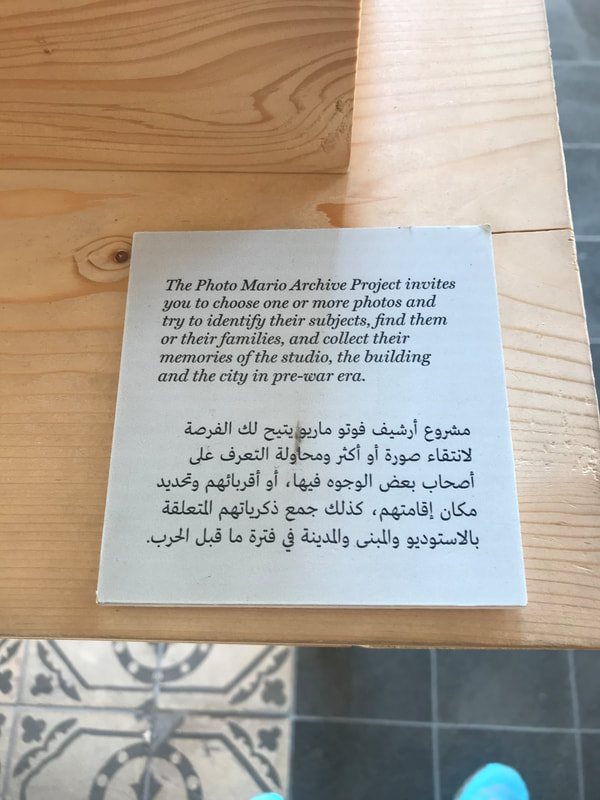

The border between East and West Beirut became an important demarcation between warring factions and hence the site of extreme violence and destruction. The “yellow house” is located exactly on this border, known as the Green Line, which is now marked and visible to visitors through a plexiglass viewport on the ground floor. Snipers seized the opportunity to use the building’s central void simultaneously as a vantage point and shield. The yellow house was ravaged by bullets, fire, and death as its pockmarked walls still attest. Even after the war ended, the building continued to be violated by vandals. Slated for demolition in 1997, a group of heritage activists led by Mona El Hallak saved the building. After extensive stabilization and the addition of a modern annex, Beit Beirut opened to the public in 2016 as a cultural center and museum dedicated to the 7,000 year history of the city of Beirut with a special focus on the war. Mona El Hallak herself curated the current exhibit, “The Photo Mario Project,” which showcases the photographic archive found in a long ago abandoned photo studio on the ground floor. Hallak interprets the negatives and photos as a “technology of memory that not only documents the past but calls it into the present.” Rather than simply displaying the negatives and photos as “time capsules” which captured lost pre-war moments and processes, she urges the viewer to “adopt… photos and try to identify subjects” in order to recreate the memories captured by Photo Mario. Hallak hopes to not only recover “the stories of the subjects” but also to create new stories of the project’s participants and how they are impacted in their attempts/potential failure at identifying subjects. In doing so, Hallak will add to Beit Beirut’s permanent collection, examining how Lebanon has transformed and endured since Photo Mario shuttered its doors for the last time. The third floor exhibit, “Childhood: Interrupted,” presents new photography by Jacob Russell focused on child labor in Lebanon, particularly in light of a more recent conflict: the ongoing war in neighboring Syria. Sponsored by the Ministry of Social Affairs and International Rescue Committee: Child Protection Program, this exhibit compassionately presents the “little heroes” whose childhoods have been interrupted. The exhibit aims to “influence change” to benefit these children working long hours at such a tender age. In addition to making the viewer aware of the realities and dangers child laborers face, handouts further educate about Do’s and Don’ts when interacting with these children. Although the Lebanese Civil War has permanently changed Beirut and the yellow house, it has left more than merely the story of loss and tragedy but also the story of resilience and survival under extreme conditions. The exhibits today add to these stories, highlighting the power of memory and childhood when confronted with pain. Beit Beirut is not stuck in the horrors of the war nor the seemingly innocent time before it. Neither does the museum attempt to quickly brush past the conflict. Rather, Beit Beirut is anchored in the present moment as a culmination of the past and conduit into the future. And as a parting gift to you, dear reader—haiku I wrote about this building and its exhibits: photo studio offers snapshots of the past exposed to great loss. children who labor, begging in Beirut daily. why them and not me? Barakat Building, it was called before the war, but now Beit Beirut.

0 Comments

CommentsYour comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed