|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

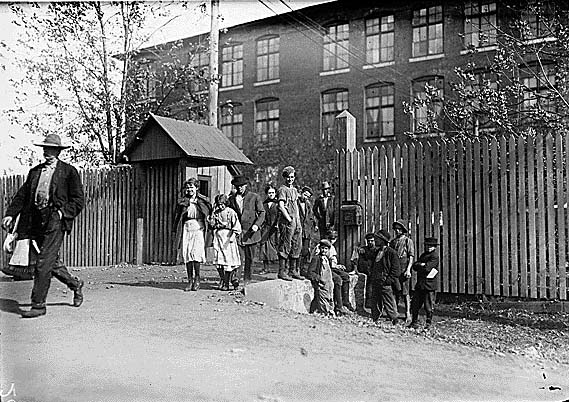

Labor Day By Patrick Michael Clark QuailBellMagazine.com There were three bedrooms in our house on Front Street. Our parents had one with a double closet and the baby Nickolas had the small one in the back. My brother Don and I shared the last room and it was always a sorry state because Don’s side was always a mess, but I didn’t mind because he was good about paying me five cents to use the safe I had under my bedpost. It was just a loose board that you could pull up and hide whatever you wanted underneath. I rarely used it but Don would always rent it if he needed to hide gum or cigarettes. An extra nickel always came in handy. But the best part about the room was that it was closest to the back stairs that led down to the kitchen and out the side yard. There wasn’t a lot to stop you from skipping out late, as long as you didn’t wake the baby Nickolas or get caught by Margret Little from across the street sitting on her porch drinking gin. It was getting to be the end of the summer of 1931, I was almost nine years old, and we were about to go back to the Monongahela Central School. It was the last week of vacation and Don had woken me up in the middle of the night. Not completely strange, but it was a lot later than usual. “Ann, I need you to open the safe.” I tried to ignore him but he shook me hard on the shoulder. “Come on, I gotta get in.” Grudgingly I got up and I told him to help me push the bed over so I could get to the hiding place. In a flash he had pulled a small paper bag from the safe, set it on his bed, and was rummaging through the closet. “What’s the matter?” I asked. “I got business up on the Hill,” he replied taking his BB gun out of the closet and slinging it over his shoulder. “This late? What’s going on?” He had started putting on his shoes. “Nothing a girl needs to know.” At this I grabbed the bag and dumped it out on the nightstand. It was full of matchbooks and ten-cent fireworks. Don got up and started grabbing the loot. “You told me you didn’t have any leftover!” I said. “I didn’t, they’re Joe Crawford’s. I’m holding them for him.” “What are you gonna use them for?” Don groaned and began tying his shoes. “I guess I’ll tell you, but you better not blab it.” I promised, but to be sure Don made me solemnly swear on the photo of Honus Wagner that hung on his wall. “Well,” he said lowering his voice, “Joe and me are gonna go up the Hill and give Frank Kaminski and the Polack kids what for. So don’t tell nobody.” “I’m coming with you then.” I said. This was probably going to be the last big thing to happen before school started up again and I wasn’t planning on missing it. “Nah, you can’t.” Don said putting a metal tube of BB’s into his pants pocket. “It’s too dangerous and you’re just gonna get in the way. And if I get killed, who’s gonna take care of the baby Nickolas? Don’t worry, I’ll be back for breakfast.” This was the weakest excuse he had ever given me, and in all fairness I had been in just as many scrapes as him. But since I had already swore to die on a photo of the Flying Dutchman, I didn’t have many options. “I hope Frank Kaminski kills you then! I hope he cuts you up and feeds you to his stupid dog!” I said as Don stepped out of the room. He gave me a salute and shut the door. As soon as he was gone, I started getting dressed. I knew where Don was going because always met up with Joe Crawford and his brother Carl in the same place whenever they were plotting something. They would be getting together in the overgrown lot behind the Town House Hotel and then setting off for the Hill. It usually took fifteen minutes to walk down High Street to the center of Dunlap Creek, down to the district they called the Neck. But since Don was already ahead of me I cut through the alleys and yards of the well-to-do neighborhood that sat above downtown, then snuck down the gravel road that wound behind the Presbyterian Church. It spat me out right by the Town House Hotel and sure as anything I saw three figures standing near the lamppost. I know I scared Don sneaking up behind him. He got clumsy with his BB gun and dropped it on the ground. Carl Crawford laughed. His older brother told him to shut up. “It's just Ann,” Don said picking up his gun. “If it’s just Ann then why were you spooked?” I asked. Carl laughed again and Joe hit him on the arm. “Unless you know the password you gotta get outta here,” the older Crawford spat. “Little Caesar,” I replied. “She got it right,” Joe said. “Guess she’s coming along.” Don groaned and started walking. We were well armed, the four of us, as we moved through the shadows along High Street. Don and Joe both had their guns and I had my pocketknife. Carl had made off with a cousin’s baseball bat. There was nobody to notice this because Dunlap Creek kept working man’s hours and generally shut down on weeknights around seven. Only the movie house kept its blue and gold lights on until ten-thirty. Soon we left the storefronts and offices of the Neck behind and climbed the narrow sidewalk up the Hill to the Polish district. Don shushed us as we made our way past the blocks of company houses. Most of the Hill worked for the Monongahela Barge Company or the Norfolk Southern Railroad and were fast asleep. Over a hundred alarm clocks ticking and set for five-thirty. A dull pink house came into view by the light of the corner streetlamp. I know it was Frank Kaminski’s house because we used to pass it on the way to Pershing Field before the kids on the Hill took it over and would throw rocks at anyone from across town that tried to use it. So we kicked them out of the Calvary Cemetery whenever they tried to go there at night to smoke. That’s how the feud started and that’s how it had been going for as long as anyone could remember. “Everyone get down!” Don commanded. We hit the ground and laid flat, thinking we had been seen. After a couple seconds we retreated to a line of bushes between the houses and crept into the backyard where our target was to be found. Leaning against a wooden-frame swing set was what could have only been Frank Kaminski’s bicycle. “Here we go, two birds with one stone,” Joe said. “Ann, you watch the street. Carl, you watch the other yard.” A moment later, Don was setting the fireworks along the rickety supports of the swing set. Joe had pulled a small container from his pocket and was smearing a kind of grease on the seat of the bike, the tires, and then the rest on the side of the swings. “Hurry, his dog might wake up!” I said from my post. Don had lit a match but it had gone out he grabbed another one. Quickly he crossed himself and began lighting the fuses, Joe had already touched off the bike seat. “Go on, run!” Joe shouted. The first firework crackled loudly, shooting sparks into the air above the swing set. Joe grabbed my brother and they bolted out of the yard. The four of us were soon racing though the Hill making for downtown as the fireworks whistled behind us. We ran to the Neck and then for another five blocks before Carl nearly collapsed on the sidewalk. Joe insisted that we couldn’t leave him so we snuck up the gravel road and rested in the ditch where we wouldn’t be seen. By then the window lights on the Hill had lit up and we could hear the distant sounds of sirens. “Carl, you go home,” Joe commanded. “Take the gravel road and cut back through the cemetery. Don’t let anyone see you.” He protested but we took a vote and decided three to one that it would be best if he went home because he was the littlest and dead tired. But we weren’t worried, he knew his way. The three of us cut through the yards I had come through on the way down, though by now we had to be deadly careful since half of Dunlap Creek had been woken up. Thankfully we could see that the houses on Front Street were still dark. Joe split off from us when we reached the corner of Front and Third. “We really gave ‘em hell,” Joe said. “Yeah, let's see the Polack try and run us down now,” my brother replied. They shook hands, swore to secrecy, and Joe disappeared. Don and I were within sight of our block when we heard a siren. Sliding into the safety of the alley, we caught a look at the red lights blinking up and down the narrow street. The police car pulled to a stop at the corner. “He’s blocked us off from home,” I whispered. “What are we gonna do?” Don said. “Hide your gun. You don’t want them to shoot you down, do you?” He complained a bit but he finally hid the BB gun in a garbage can and said he’d get it in the morning. Suddenly we heard the police car start up again and move towards us, the lights growing brighter against the buildings nearby. We turned and ran wildly away from the lights, coming to the end of the street where the pavement turned back towards downtown. Then an exit came into view, a door left propped open. “Here, let’s hide in here,” I said moving towards the basement door. Don had stopped completely. “Don’t you know what that is? We can’t go in there,” he insisted. “It doesn’t matter. You won’t go to hell.” He didn’t move. We could hear a car approaching. “You wanna get caught?” I asked. At that he took the plunge and rushed inside. I followed and closed the door behind us. Despite that fact that he had blown up Frank Kaminski’s swings and burned his bike with cooking fat and matches, Don had been afraid to set foot inside our newfound hiding place. This was because it was the Slovak church and it was only for the Slovaks. Even the Polish and Irish in Dunlap Creek, although they were all the same religion, never went to the Slovak church. Our parents were Serbs, which made my brother and me Serbs, along with our Uncle Leon and cousins who lived in town. We had our own church across the river with gold onion domes on the roof, but out of mortal necessity we were now holed up in the basement of the Church of the Immaculate Heart. “You have a match?” I asked. The hallway was dark and we didn’t dare to look for the light switch. Don struck one nervously and we looked around. All seemed normal, until we heard voices coming from the end of the hallway and saw a light behind a cracked door. I stuck my head in the open space. Don was behind me. “What’s in there?” he asked softly. “It's some kind of meeting,” I replied. I opened the door slowly and we snuck into the room. The church hall was crowded and lit by bright halogen lights. It was almost all men in the room, some sitting and some standing, a few with their wives. A podium was at one end of the hall with some important-looking people sitting nearby, two priests in black robes, and a speaker at the stand. “I ask you, how many times are we going to allow this to happen, fellow workers? Allow these paid strike-breakers and tinhorn soldiers with Legion badges to club us and shoot us like cattle?” The crowd yelled in response, the speaker wiped his forehead with a handkerchief. “Only look to the past, workers. Haymarket, Cleveland, nationwide demonstrations of railroad workers and trade union men! And what was the response? Pinkertons, state militia, mobs paid by the bosses!” This brought another shout from the crowd. Some sounded in agreement. Some sounded in anger. “How many of the dockworkers on this very river are organized? Not enough! How many of you from Perryopoplis and Scottdale are sure of a livable wage and legal protection in a union of your own? None I that can tell you of! None!” A man rose from the crowd, his hat in his hand. Don watched him then turned to me. “Ann, that’s Mr. Kaminski!” “Do you think he’ll recognize us?” I whispered. “No, just keep low.” Mr. Kaminski raised his voice at the speaker. The crowd quieted. “So what would you have us do then?” the Polish man replied. “Join the Industrial Workers? Don’t try and dupe me Mister Chicago, I’m a working man but I’m no Red!” The crowd argued. A second man rose from his seat. “It’s Mr. Crawford,” Don said. “And you’d have us keep breaking our backs for nothing then?” Joe’s father snapped. “Read the papers, Kaminski. Nothing’s getting better since U.S. Steel won’t negotiate. Everyone on this river’s gettin’ kicked in the gut.” “I believe you!” Mr. Kaminski shouted. “But should we solve our own problems or should we listen to this Communist?” One of the priests stood up, calling for order. The lights had gotten hotter and I was starting to sweat. “Call the vote now!” Someone in the crowd shouted. The priest moved toward the podium, the representative from the Industrial Workers of the World returning to his seat, though not before invoking the brotherhood of man and the name of Mother Jones. The priest’s voice was soft, but confident. “We’ve heard the various labor representatives speak. Now I implore you consider what you know to be best for your families, for your children and community. The vote will be held at the Croatian Hall in West Dunlap Township in one week’s time. All in favor?” At least half the crowd must have responded with “aye” because the priest closed the meeting and began a prayer. Don tugged on my shoulder. We slipped out of the room and went down the dark hallway again. The two of us moved quickly between the rectory house and the high wall of the pale-brick church. Then we stopped again. There were headlights in the street and what sounded like angry voices on the sidewalk. “Come on then, Reds!” A man’s voice shouted from across the way. We waited near the porch of the rectory, a shadow keeping us hidden from view. But Don and I could see plainly in the lights of the streetlamps and headlights of parked Fords the large crowd of men that had gathered opposite us. Some of them had lanterns, some had rifles. A troop of Legion men in uniform stood in a line, their polished buttons and silver hat badges reflecting in the glare of the light from the cars. An American flag hung on a pole above the crowd along with the Pennsylvania state colors. “Bolsheviks! Traitors!” another voice called. I moved up into the street enough to see the other crowd. The men and women from the meeting were now standing in front of the doors of the Slovak church. I saw the faces of Mr. Kaminski and Mr. Crawford, the speaker in the red tie, and the priest in the black robe. Don was next to me and I held his hand. “Well, aren’t you gonna do something?” a voice across the street yelled. “We’re not moving! Go on make the first cut!” came the reply. Nobody seemed to be doing any cutting. It had grown quiet. They just stood there looking at each other, motionless as the statues at the Soldiers and Sailors Hall. Then there was a break in the silence, a sound coming from what seemed like darkness. A man’s voice singing, first softly, then growing. “The Sacred Heart, all burning, with fervent love for men, My heart with fondest yearning shall raise its joyful strain!” Other voices had joined in and I could even see Mr. Crawford’s moving his lips along. “While ages course along, blest be with the loudest song, The Sacred Heart surrounded, by every heart and tongue!” Then from across the street there came another sound. It was larger, trying to drown out the opposite crowd. “My country ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing! Land where my fathers died! Land of the Pilgrims’ pride!” The men in front of the church grew louder. “Too true I have forsaken, Thy fervent love for men!” A roar came from the American Legion. “From every mountainside, let freedom ring!” Then another fiercer sound, a third group of voices. “Solidarity forever! Solidarity forever! Solidarity forever! But the Union makes us strong!” Don started pulling me back towards the shadow of the rectory house, the alley that would lead us back home. “Our fathers’ prayers, to Thee, author of Liberty! To Thee we sing! Long may our land be bright, with freedom’s holy light.” He tugged harder. I watched the face of Mr. Kaminski among the crowd. The words had mingled into something else. “When the Union’s inspiration through the worker’s blood shall run, There can be no power greater anywhere beneath the sun!” We turned and started running down the alley, a block away we could still hear them. “The Sacred Heart surrounded, by every heart and tongue!” Then we were at Front Street. The upstairs lights in our house shining through the windows. “Land where my fathers died! Land of the Pilgrims’ pride.” I needed to breathe. I needed to stop. “Now we stand outcast and starving, ‘mid the wonders we have made But the Union makes us strong!” I turned to look over my shoulder. I saw my brother and I saw the lights from down the street. “From every mountainside, let freedom ring!” Then we heard sirens. “Solidarity forever! Solidarity forever!” We rushed into the kitchen though the screen door. Don leaned against the counter panting. I could hear the baby Nickolas crying upstairs. #Unreal #ShortStory #Fiction #CreativeWriting #LaborDay #1930s #HistoricalFiction #GenreFiction #PatrickMichaelClark Visit our shop and subscribe. Sponsor us. Submit and become a contributor. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter. CommentsComments are closed.

|