|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

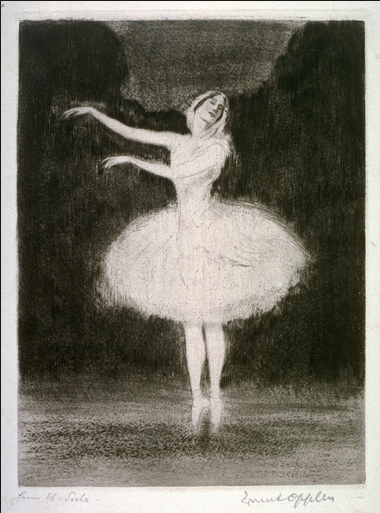

The Dancer

Every evening, dear girl, I return home from work to find your grandmother waiting for me at that old wooden table where a pair of large, beautiful eyes once made us a family. As I sit down, she gets up wordlessly and begins to busy herself at the stove. I confide my heaviness to the doll by your grandmother’s vacant table and she tucks them underneath her with graceful ease. Your grandmother and I wordlessly sip our tea. Looking into your grandmother’s face, I wonder how she’s so much more beautiful now that wrinkles have conquered every inch of that soft, smooth face that expressionlessly registered the ardent kisses of my youth. She gives me a querulous smile. Our tea over, we rise as one and painfully make our way to that little room we pace endlessly in our dreams, sometimes aware of each other’s presence. Your mother lived here and it is exactly the same as the last night she slept in it. Your grandmother sits on your mother’s chair and plays with the scraps of paper and ribbon your mother used to store in an old cigarette tin. When your mother was so much more than a grim voice on the telephone and the plaintive silence that followed, she and your grandmother would quarrel over these strange captives to your mother’s fancy. What your grandmother saw as garbage, your mother saw as the beginnings of beauty. Your mother was, even when she was three and growing anxious that she would outgrow the little cardboard box she had designated as her home, an artist. As your grandmother grumbles irritably over the little intangibles dear to your mother’s heart, I flip the pages of her diaries, diaries filled with the minuscule handwriting that made her teachers furious. They all had high hopes for your mother, a girl who was already someone whose moments of unconscious beauty brought tears to their eyes. Even in her happier years, even in those days she took for granted – how couldn’t she? – the admiring tribute of her playmates, your mother was a very serious girl. This seriousness was hidden under her cheerfulness; it was the worry in the hugs she gave her dour mother, the concern in her laughter over her playmates’ slips and falls. Even then, she laughed to comfort, to make little those sudden onslaughts of grief that make the lives of little people fraught, and so transparent was the child who worried she was opaque that her friends – and there were so many – knew she was never laughing at them. I am not much of a reader. Sometimes, I bring home the children’s magazines in the waiting room of the doctor I work for. I always read the joke columns. But even I can recognize the beauty in my daughter’s writing. I never read too much of it, so moved am I by the manner in which her tiny words are animated by a desperate attempt to understand the world and herself. Even when her face was bright, even when she smiled and danced, we knew our daughter was a worrier. We just didn’t know how much. Your mother, who was already reading large, fat books with no pictures in them when she was five, worried about my seeming ignorance. And often, on the evenings when I would have liked nothing better than to puzzle over the puzzling spirit in my arms, she would tell me the stories in the books she was reading, pausing to question me severely. This would eventually win her a stern scolding from your grandmother, who pretended to see arrogance in her daughter’s unusual articulacy. Like your mother, your grandmother is a worrier – it was her fear that the daughter she doted on with all her large heart, with all the tenderness she kept hidden from her once-teasing husband, was too extraordinary. Your mother was always angry when your grandmother interrupted her thus. She would grow sullen and withdraw from us. She would return an hour later, evidently herself again. But then, she outgrew this anger. Perhaps she had begun to understand just how much our love for her made us as much her captives as her slivers of ribbon and paper. Neither your grandmother nor I are particularly brave. Your grandmother (who bought your mother notebooks we could ill-afford), tortured by her family’s contempt for her beautiful line drawings, destroyed all her art before moving to the city to become a maidservant at one of those large blocks of flats that seem to spring up everywhere. I met her when I traveled with my boss on his visit to your mother’s then mistress (a lady who ate too many chocolates). And I was too terrified to leave my comfortable employment to aspire for better things. I let my hard-won commerce degree acquire dust. I accepted that I would always be overlooked by the men and women who walked in and out of my employer’s office, always little more than the pen that filled in their appointments. Together, we never dared to look for anything better than the little flat your grandmother’s mistress allotted to us in the servants quarters, knowing that this way your grandmother would always be on call. Do you understand then how much we loved and feared your mother? She was Courage, possessed of a brightness that both warmed and singed us. Once, however, she was also Joy. Even though, as I said, she was always a worrier. She was a handsome girl, a talented child, a spirit that sang and danced and wrote. It was her headmistress who paid for her training in that ancient dance form that compresses a lifetime of experience into a single short, fluid movement. Joy has its detractors. And even though my cheerful, helpful daughter had few enemies among the servant families that played out their daily dramas by the parked cars of the apartment blocks, she was aware that my grandmother’s mistress hated her. Your grandmother’s mistress was a firm believer that everyone should know their place. She believed your mother didn’t know her place, furious that my creative, passionate child refused to be a meek silence. When your grandmother was occupied with her many household duties, her mistress would send your mother to the market or to the washerwoman, an hour’s walk away, to fetch her laundry. When your mother demanded payment, the chocolate-addicted woman slapped her – to her, your mother was only an extension of her mother, bound to her whims by your grandmother’s meager salary.

I don’t think your mother really minded. She liked to work and she liked the fresh air. And the monotony of her work allowed her mind to build the great forts and castles wherein resided her best work. Besides, your mother had a quiet, sincere love for the woman’s daughter, a sullen, overweight thing who was harassed by her mother’s attempts to fit her into a mould she could never aspire to.

I could never like this child, whose weakness soon turned to viciousness. But your mother felt a kinship for her, never minding that the child stuck up her nose at her plain clothes, or pinched and scratched her when she was angry. Like your grandmother, she knew she was less flesh than wood to a girl brought up to believe servants were implicitly inferior. When your mother was ten, her fond headmistress gifted her a diary whose beautiful cover was illustrated with birds. She knew my daughter’s slender feet never rested on the ground. That is, then. The diary became your mother’s dearest possession and she carried it everywhere. She even slept with it under her pillow. Then she made the mistake of showing it to the girl whose only friend she was. Instantly, the girl coveted it. She took it from her. “If you value my friendship, you’ll give it to me,” she told your mother. Your grandmother’s mistress, who was watching television in the living room, had heard this exchange. She called out to your mother. “What would you do with a diary anyway?” she sneered. Your mother didn’t abandon the lonely girl. She had her friends and her loving teachers. I dare say, she had us. She puzzled over her headmistress’ brief coldness, never realizing that the headmistress had assumed she’d lost the diary she had bought with such care. Years later, when I told her what had really happened, that wonderful woman wept. At fifteen, your mother was so lovely it hurt our eyes to look at her. She was a mixture of strength and gentleness, grace and fire. But there was a sadness in her beauty and it broke our hearts. Her room was full of trophies – she won so many of them in dance competitions. My wife clipped out the articles she appeared in and saved them. On your mother’s sixteenth birthday, we pooled together our salaries and bought your mother a pair of ballet shoes. Never content with her achievements, never resigned to rest, your mother wanted to become proficient in yet another dance form. That same night, your grandmother’s mistress sent your mother to the ice cream parlor with her daughter. That child, depressed, had demanded the company of the girl she despised. They were standing outside the parlor, your mother gamely licking at the cheapest lolly money could buy, and attempting to cheer up her tearful friend, when one of the neighbors, a pretty woman who admired your mother’s daintiness, saw her and rushed towards her. “I saw your performance at Siri Fort,” she told her, “You were lovely.” It is only at this moment that I have any sympathy for that fractured creature who was the least of my daughter’s friends and the sorrow that would suffuse her life. Always a nonentity, never able to love the mother who controlled her every action, resentful of the friend whose love she knew was never really her due, she howled in rage. She pushed your mother into the street and as a speeding bus hit your startled mother, your grandmother woke up from a troubled sleep, screaming. Your mother grew used to the pins in her legs, to the way the curiosity of passers-by sometimes slipped into a teasing all the more painful because it was as free of malice as the jeering of a child. Sometimes, your mother wondered if she would grow up to be like the people who persecuted her before being won over by the sadness in her eyes. I never saw your mother smile after that day. But then, I never saw her cry. Not even when we rushed her side at the hospital. Ignoring the feet that would never again be the slender slivers a lovesick classmate had penned a poem to, she looked me in the eye and said, “I’ll become a writer.” And when your grandmother started crying, it was your mother who attempted to console her. But your grandmother was heartbroken at your mother’s desperate attempt at strength – she knew her troublesome beloved would break down. Your mother did break down. But this was years later and she was already a published writer whose slender first novel her mother had stitched into a pillow and slept on. Our daughter had returned home after eight long years, years in which she had made her talent known to the world. She was limping by my side, dragging her right foot along, when a little child, the daughter of one of the building’s new residents, paused on her way to ballet practice to run over to my daughter. She began to imitate her. But my daughter, whose eyes were fixed on the girl’s slender shoes, had already begun to scream. My daughter spent a month in hospital. Luckily, she could afford private health care. I shudder to think of my lovely daughter in the filthy republic of neglect that is a government mental hospital. And then she went straight to the airport. When she called us a month later, she didn’t say she was sorry. She didn’t call us to her wedding, two years later, to a man who loved her with something of our desperation, a man who forgave her silences because he knew the rainy music her feet had once danced to, the music her mind still danced to, a man who was ready to reside in the beautiful world your mother had built with her unshed tears, a world whose first citizen will always be you. Two years later, your grandmother’s mistress died. By then, your grandmother had already left her employ and was working for a merry little woman who really wanted a surrogate mother to replace the delighted parent she’d enchanted to death. Missing your mother, dimly aware of the faery child that was you, your grandmother was only too glad to comply. I still worked at the doctor’s office, increasingly indispensable to my absentminded boss, but I only looked forward to those moments a little child would visit our home. Your mother, in unknowing cruelty, had forgiven her last persecutor when she visited her in the hospital – and our wonderful new friend was no longer a stranger to remorse. You will meet her today. She is dying to meet you. She, too, is a writer. Sadly, the other child your mother had an unintentional effect on didn’t grow up. Still an overgrown child when your grandmother’s mistress died, her daughter was unable to endure being bereft of the last person who had truly loved her. She was committed. She died when you were five, your mother’s diary still in her possession. Unlike your mother, who’d always been the queen of her ordered imagination, this poor child had been a slave in her own dark kingdom. Finally, she was free. I am glad to know that in her last days, your mother was planning to come home. Perhaps, this is why she didn’t call for us, perhaps in her pain she closed her eyes and, as you say, dreamt of the eucalyptus tree she used to climb and whose branches she would fashion into toothbrushes, of the street dogs who were her first and most loyal friends, of the headmistress who still finds herself parceling leftovers for her favorite student. Perhaps your mother had been home already in the magazines your headmistress sent us, in the increasingly despairing novels your grandmother’s new employer bought for us, in the university students returning to India who would visit us to see the parents their favorite professor spoke so fondly of. I know you will forgive an old man’s garrulity. You see, looking at the photographs of your childhood, I delight to see that in many of them, captured (but what an illusion that captivity is), in movements more poetic than your mother’s most elegant words, you are wearing the same shoes. Those ballet shoes your mother never got to wear. And so I know, finally, it wasn’t a mistake to send them to her. #UnReal #MentalIllness #Ballet #Dance #India #Parents #Family #Caste #Legacy

Visit our shop and subscribe. Sponsor us. Submit and become a contributor. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

CommentsComments are closed.

|