|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

Jumby

By Jody Rathgeb

QuailBellMagazine.com *Editor's Note: First published in The Carribean Writer, Vol. 27, 2013)..

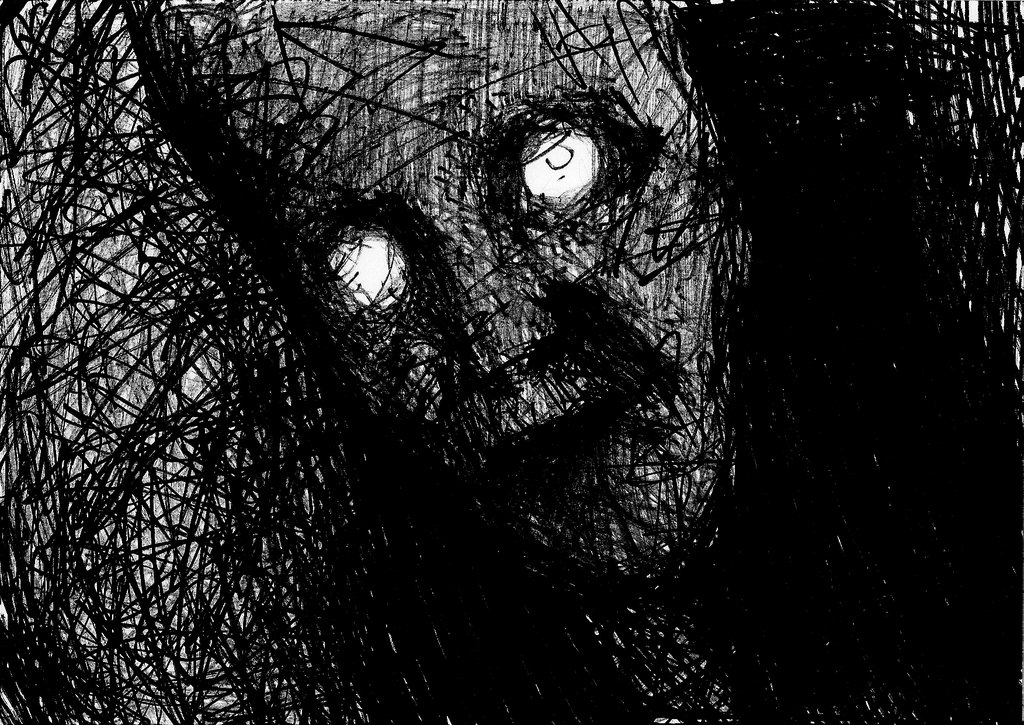

Gareth Williams had been buried three days when I met him on the path between Wade’s Green Plantation and Kew.

“When you gonna do right by me?” he demanded. I was startled but not frightened, even though I was alone at dusk, and the path was deserted except for Gareth and me. I was often late in closing the tourist hut at the plantation, and I never had qualms about walking home alone. The National Trust had hired me as a caretaker and ticket-taker several years before, so by now I knew most of the islanders and they knew me. They had found my story—the old, boring one of a divorcee making a new start abroad—interesting for a while, and then I became just another part of island life. Some knew my name, but to most I was “that white woman works up at Wade’s Green.” No, I wasn’t scared, just puzzled, briefly doubting what I knew to be true. Didn’t we just bury Gareth, I thought, certain that I had been to the funeral. And when did I not “do right” by him? The only times I had heard that phrase was when one islander owed something—money, a borrowed item, a favor—to another, and I had no debts with Gareth. In truth, I had little connection with him at all. I had enjoyed watching the wiry old man build a wall around my landlord’s yard, and we had talked pleasantly about how he’d learned to do stonework, the proper way (his way) of building a wall and the shame that few young people on the islands were taking up such a trade. After the wall was built, I saw him only rarely, usually when the mangoes ripened on the tree next to my rented house. Gareth loved mangoes and knew everywhere to find them on the island. He also knew that I couldn’t possibly keep up with the amount of fruit “my” tree bore, so he would arrive with a plastic bag to collect his fill. In fact, it was because he was holding a mango that I recognized Gareth on that path. Otherwise, he was considerably changed. His face was an ashy white, as if his dark brown skin had been smoldering like charcoal. His eyes were reddish and glowing, and his magnificent tribal-king crown of gray hair appeared to be throwing off sparks. I really should have been frightened. But then I saw that mango and thought: Gareth. “Well? When you gonna do right by me?” he repeated. Instead of answering, I said what I had finally realized: “You’re a jumby.” “A jumby? How dare you!” he said, and he disappeared. The effect was thrilling. “A jumby! I saw a jumby!” I said to myself, hurrying home. I had first heard about these ghosts—actually, more like zombies, minus the George Romero histrionics—one night eavesdropping at the local bar, where the guys were trying to top each other with outlandish stories. Once home after actually meeting a jumby, I went straight to the Internet but found disappointingly thin information. Yes, the word was a version of “zombie” and derived from voodoo. And yes, a jumby was “undead”—caught between life and death, either by design or by accident of unfinished business. But I craved a description and, more importantly, a reason that Gareth would appear to me instead of a relative or friend. The next day, as I led a group of schoolchildren around the plantation site, I briefly thought about adding a jumby tale to my spiel … perhaps a slave jumby admonishing a harsh master? But one glance at the teachers—serious disciplinarians and members of the Christian sisterhoods that would frown on such superstition—set me straight. This particular bit of folklore was best saved for the tourists. I didn’t want the island chattering about the white woman who claimed she saw a jumby. But then, after the children left and I was latching the gate, I saw Gareth again. He was standing atop the stone wall around the overseer’s house … well, not standing, but somewhat floating. He looked like he was solidly planted, but his feet hovered about three inches above the wall. Again, his eyes burned and his hair sparked. “You tell them children. You tell them,” he said. I was no less astonished than I had been the night before, not least because of this hovering. “Gareth?” I called, just to be sure. He nodded. “What do you want?” I asked. “You do right by me,” he said, then faded from sight. “Gareth?” I called again … but he was gone. Now I knew I was being haunted, but I had no clue as to why or how to deal with it. I went back to the tourist hut and tried to collect myself. I was somehow pleased to be part of a cultural phenomenon, but I had so many questions. Why was Gareth a jumby, and not just dead? Why was he appearing to me? What did it mean? I resolved to visit Alvarez. Mangoes were what I had in common with both Gareth and Alvarez. She would also visit my tree, always stopping to ask permission and chat awhile. Although most people on the island dismissed her as crazy, I enjoyed hearing her talk about the island in the days before electricity, phones and television. She wasn’t that old—60 or 65 at most—but she had been an only child and then a spinster caring for her parents until they died, so she seemed to have a soul as old as them. So much about her was unusual, from her name—her father, a seafarer, had picked it up in his travels, she explained—to her fierce independence. She was a big, tall woman, smooth-skinned and handsome, and she seemed to prefer her own company. Few would greet her as she walked along the road, swinging a machete and conversing loudly with herself. Those who did would get a steely glare or admonishment. It was said she was talking with her parents; it was said she had been left wealthy even though she still lived in a shack in Sandy Point; it was said she saw jumbies. I had no other tours planned for the afternoon, so I left a note on the door, walked home and plucked two ripe mangoes. I then biked to Sandy Point, trying to phrase how I would ask about my jumby. I needn’t have bothered rehearsing. Alvarez threw open her door at my first knock and spoke first. “I’m headed to the back,” she said. “Come along.” She handed me a machete and used hers to push me aside as she stepped out of the shack. I followed. We wove through the maze of growing vegetables that took the place of a backyard until we arrived at a stand of squatty palms. “Cut here,” she said, deftly lopping off a palm frond. “All but those ones in the center.” I followed her example, clumsily, and we started a pile of fronds. At first, we worked silently; it was too much work to keep from slicing my own hand for me to try talking. But after I developed a rhythm and some confidence, I asked about our purpose. “We’ll make hats,” she answered. “I’ll show you.” I was pleased and flattered that she thought enough of me to propose this. I had admired the straw hats Alvarez made and, as with Gareth, I was curious about these traditional crafts and trades. So I worked hard at the cutting to please her. But my original purpose for being there was too strong to ignore. “I saw a jumby,” I announced, borrowing her abruptness. She stopped cutting. “Who?” “Gareth Williams.” She nodded, not surprised. “We have enough,” she said. “I’ll have the boy collect them later. Let’s have a glass of water.” We went back to her shack, where I sat in a sagging armchair and recounted my jumby story. She wanted particulars: What did he look like, what did he say, was he holding anything? She seemed pleased with my answers. “He is really a jumby,” she stated. “You saw that his feet didn’t touch the ground.” “Why me?” I asked. “I hardly knew him.” She asked how I did know him, and I told her about our conversations at the wall and the mango tree. “So why me?” I asked again. “What do you want?” she countered. “I want him to rest,” I said, figuring that this was a better thing to say than, “I don’t want to be haunted.” Alvarez paused a while before speaking again. When she finally did, I felt that it wasn’t exactly me she was talking to. “One way to send a jumby on is the 23rd Psalm,” she said, considering a corner of her kitchen ceiling. “Another is to give it rum. Or what it wants.” It didn’t take long for me to be able to use this information. Gareth showed up within a few days. This time, he was in my yard just before bedtime, when I opened the door for the cat. I saw him under the mango tree, and this time I didn’t startle. “Gareth,” I said simply. “You learnin’,” he said. “The Lord is my shepherd,” I replied. He put up a hand in a gesture that left a trail of what looked like ashes. “No good,” he said. “Okay, wait.” Leaving the door open, I dashed back into my kitchen, then came out again, leading with a pint of rum. He smiled, sending off a few sparks. “Thank you, no,” he said, and once again he faded. I reported this to Alvarez while helping her gather strips of our palm from the sea water in which they had been soaking. We spread them out to dry in the bare, rocky section of her yard, anchoring the strips with rocks in case a wind arose. “Gareth can be different,” she said. “You know, I saw him too.” “You mean recently? As a jumby? What did he say?” Alvarez just shrugged. “He asked if I still make mango juice. I told him yes, and he went away. I’ll leave some for him tonight.” I felt frustrated that Alvarez wasn’t helping me with my problem. “How about if I give him the juice?” I suggested. “Won’t work,” she grunted, slapping a huge handful of palm against a rock. But giving the jumby mango juice did seem to satisfy him, at least for a while. I didn’t see him for more than a month. I might have even forgotten him, except for my hat-making visits to Alvarez. We didn’t always talk about him, but his name came up occasionally as I learned how to plait the “cured” palm strips and tried, mostly unsuccessfully, to imitate the older woman’s skilled motions as she shaped and sewed the braids into a hat. It turned out that he had once been a beau, before Gareth met the Bahamian woman he married. Alvarez hadn’t been too upset by the switch; her parents hadn’t taken to the rough stoneworker, and she had been neutral all along. She didn’t see the logic of becoming a wife when she was, essentially, a princess in her own home. As adults, Alvarez and Gareth had been cordial but not close. She said she admired his work but had never needed a patio or wall. She didn’t know if, in the Bahamian woman, he had ever lacked for someone who could make a laundry detergent from papaya leaves or grow and grind corn for a fine johnnycake. I was, in my emotional and island-smitten way, captured by this aborted love story, making much more of it than Alvarez told. I imagined a stern-father scene, a furtive meeting on the beach, an awkward estrangement of 20 years. None of it was true. Instead, there was just this jumby and me, of all people. As if to underline my foolishness, Gareth appeared again at the height of my imaginings, late one afternoon as I biked home from Alvarez’ shack. When I saw him directly in my path ahead, I naturally swerved—although by now I knew I could have run through him without mishap. The motion sent my bike over, and as I examined the scrape on my calf the Gareth jumby approached me. “When you gonna do right by me?” he demanded once again. I was injured, I was annoyed, and I was tired of this nonsense that I couldn’t share with anyone except Alvarez. “Gareth, go away!” I yelled. “No. You do right by me,” he said calmly, before doing his usual fade-out. I was agitated enough to turn my bike around and go back to Alvarez. “He’s driving me crazy!” I announced, bounding into her yard and surprising her in the act of doing some extra shaping on my unfinished hat. I briefly registered a grateful moment but continued my complaints: It was nerve-wracking, I didn’t ask for a jumby, there was no reason for it, the whole thing was ridiculous. Alvarez waited calmly for me to sputter out. Then she shrugged. “It’s your jumby,” she said. “It will work out.” I sighed and had nothing to say. She raised my hat a bit. “We can finish this tomorrow,” she said. “I can’t. I have to be at the plantation.” “Then I’ll go there,” she decided. Alvarez arrived while I was at the site with some students, so that as we returned I could see her sitting in front of the hut, plaiting more palm. She was a magnet to the children, who surrounded her and listened to her describe what she was doing. It was a nice addition to the tour they had taken, another bit of their heritage. “Maybe I could get you to teach them,” I suggested, after the teachers had swept the children away. “Maybe. I would like that,” she said. I picked up my hat and sat beside her, now comfortable with our work-and-talk routine. “You see him again last night?” she asked nonchalantly. “No. He left me alone. Thanks for calming me down. I guess this is just something I have to get used to.” “Maybe.” She reached over and inspected my work. “You finished,” she declared. “Try it on.” I tied it off, put on the goofy-looking thing and shot her a dramatic smile. She nodded and smiled back. And then we heard Gareth. He had appeared directly in front of us. “Yes,” he said, sparks dancing around his head. “Yes,” Alvarez repeated. I held the brim of my hat and smiled at him, watching as the sparking stopped and his skin and eyes lost their glow. He slipped downward. As his feet touched the ground, he said again, “Yes.” And he was gone for good.

#Unreal #Fiction #Jumby #TheUndead #Hauntings #Zombie-esqueStories

Visit our shop and subscribe. Sponsor us. Submit and become a contributor. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

CommentsComments are closed.

|