|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

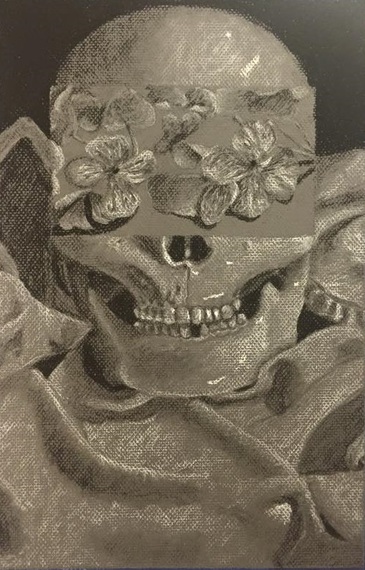

A Forest of Bones

Mild is fifteen when she opens a door under her bed. That first night only the four oldest go down, and only she steps onto the dance floor. She dances until her feet blister, but she she still can’t believe what she’s done. She’s created this world.

What’s more, she did it in her sleep. When she woke her sisters to tell them about her dream--she’d knocked on her bedpost, and seen stairs sink down, and they’d danced between a golden palace and a crystal lake, danced the night out—Valiant snapped, “Go ahead then. Knock.” They shuffled barefoot through snow as cold and sharp as diamond dust. They shivered on the lakeshore, hands linked, letting go one at a time to step into boats that skimmed across the water like floating leaves. Mild, Valiant, Amity, and Plenty: a year apart each. Mild is the oldest but doesn’t feel like it. That would be Plenty, just twelve and already the only one who dares to stand up to their father. Or maybe it’s Valiant, her sweet soft voice paired with a tongue that could strip paint. Mild’s never really been the oldest, never been their leader, but she knows that there’ve been women in her line with strange gifts. Women who let their dreams loose in the waking world. Back in their bedroom, she tells her sisters she’s an enchantress. “You just found it.” Valiant fluffs diamond flakes out of her hair. “It could have been there to begin with.” Mild shakes her head. “You’ve never been outside the palace,” says Amity, as if she could forget. “How could you dream all that up?” She goes to the schoolroom early to spin globes and read storybooks while her sisters yawn over their slates. She drinks in the places and pictures, jewel-bright, knowing she’ll see them tonight. It’s a dream world, and it won’t last unless she feeds it. She steals powder and rouge from her stepmother’s room. Valiant rounds up the younger ones. Clarity, Joy, Constance, Willingness, and Wit barely leave their nursery, but they’ll all dance tonight, and their father, who thinks he’s locked them up so tightly that they’ll never escape—they’ll dance beneath his throne. Maybe the queen suspects something (she’s the one who told Mild about the dreaming gift) but she never lets on. Another child will be born any day now. Plenty, always knowing things she shouldn’t, says it’ll be named Verity. After Verity come the twins, Silence and Noble. After them the queen dies. There have been three queens all together. The king says he won’t marry again. He’ll wait until his daughters marry to find an heir. But his kingdom is small and poor, locked in a war he’ll never win, while his daughters flutter around the palace like old dresses locked in a dark wardrobe. If any of them marry, it won’t be for years yet. Mild can’t believe their luck. She builds a pavilion by the shores of the lake and a prince for each of her sisters. Each one is ghost-soft with a foam of lace sprouting from his throat. They mouth words as if reading from a script—hers, Mild realized on the night her prince called her more beautiful than the sun and stars. There she was, stumbling in a yellow dress two sizes too small for her. A blind man wouldn’t call her beautiful. They chase each other through the snowy diamond woods, dance in the pavilion or in the palace, read book after book in a library that never ends and come home never quite remembering the stories. Mild explores every corner of her world, refining it until it seems more real than the one above ever does. It’s the best thing she’s ever done. It’s also entirely too good to last. Mild is eighteen when their father finds out. Part of her wonders why it took him so long (and why in the end did it have to be her worn out shoes that gave them away? “Walking? When have you ever walked farther than the breakfast table?” he shouts at them. Only Plenty shouts back. He asks where they’ve been going and Noble answers, “Under the floor.” Valiant says that a man who named his own daughter Clarity can’t have much to spare for himself. Their father doesn’t dare touch her, so he slaps Mild, twice for good measure, and orders them all locked in their room. That night Mild drinks red wine until her head spins, dances until her princes crumples in her arms, goes to bed, and sleeps for two days. The war ends when Mild is twenty. Their father sends out a proclamation--any man who solves the mystery of their worn out shoes will have his pick of the princesses and the throne to the kingdom when the king dies. But they’ll only have three days to complete this task. If they haven’t by sunup on the fourth day, the king will have their heads cut off. Mild goes to their father. It’s the first time she’s spoken to him since he found them out. “Don’t kill them.” She can’t believe she’s begging. “Let them try, but don’t kill them.” “A deadline,” he says. “That’s what men need. And motivation. They’ll find enough of that in your sisters, I expect. You’re not aging well, darling.” He pats Mild’s cheek as if she’s a broken doll, and the words she’d planned to say wither away. Even if she told him about her dreaming, he’d never believe it. He looks at her and sees something soft and stupid, not even fit for childbearing. She runs back to her sisters. Amity and Plenty already know what to do: they’ll dose their guests with drugged wine. A goblet-full, just enough to keep them asleep the whole night. Mild sinks to her bed, knowing she should fight this. Also knowing she’s too weary to win. “They’ll die.” Valiant sinks down beside her. “That’s father’s doing, not ours. He’s the one holding the ax.” A prince arrives the very next morning, so young and handsome that Joy begs them not to do it. Plenty hushes her while Valiant offers him the wine, her voice at its softest and sweetest. At sunup on the fourth day, their father orders the prince’s head cut off. Mild holds her sister, wiping her tears while Joy sobs as if she’ll break. She can hardly bare it, and finally she asks, “Should we stop? Do you want me to stop?” Joy quiets. She shakes her head. Mild kisses her sister and tells herself she’s not their father. She’s never killed anybody, and she never will. But there’s something new growing at the edge of the forest. Something knobby and sickly-white; a sapling that reaches out like a pair of hands. It grabs Mild’s sleeve, tearing it. It whispers to her in the dead man’s voice. Clarity beats them all back to the staircase. “You did it!” she screams at Mild. “I know you did!” She wills it away but by the next night the sapling’s grown into a tree. It bends toward her; it strokes her cheek tenderly before lashing it hard enough to draw blood. Blood, it hisses, my blood is on your hands, and, Bones, my bones are in the earth. More men come —youngest princes of poor houses; dukes, gardeners, and cobbler’s boys. More saplings sprout, and night by night the bones sink their roots deeper. Mild drinks more wine, eats more food, and dances herself senseless. This goes on for years. Then the soldier comes. Noble sees him first. “He’s at the gates,” she puffs, clutching at a stitch in her side. “He said he wanted a crack at our riddle.” “What does he look like?” asks Constance, who keeps a list of every man their father’s beheaded. When they ask her why, she never answers. Noble shrugs. “He’s bald.” “Oh, Lord.” “And he gave me this.” Noble drops something onto the floor. It’s a doll —maybe—at least it has a face, carved out of a withered turnip, that grins up at them while Noble nudges it with her shoe. Mild slaps her. She hasn’t slept for two days, and nobody cares enough to teach the younger ones manners anymore. Nobody but her. “Don’t throw gifts on the floor. Were you raised in a cave?” Her sister picks it up, sniffling. She tosses it onto her pillow just as the supper bell rings. The man’s bald, and old, but not as old as Mild expected. Rough, too. Common. Their father sits her beside him. “The eldest. Bloom’s long gone but she’s the quietest of them all. Mild by name, mild by nature.” When he smiles at her, his whole face wrinkles. Mild doesn’t smile back. Her father digs his fingers into her shoulder. She smiles. “So you’re a dollmaker?” He laughs until her sisters look away and her father, with a pained smile, says, “He’s a soldier, darling.” “Really? It was the prettiest doll we’ve ever seen, wasn’t it, Noble?” Noble mumbles a thank you while their father moves back to the head of the table. The soldier gulps from his wine glass while Mild studies him. “What did you bring? A charm? A blessing?” These days the men keep tricks up their sleeves. He wipes his mouth, shakes his head. “They haven’t helped me yet.” But he’s hiding something. Mild knows his kind, can feel them a mile off. “Then have mine,” she says. “For all the good it’ll do you.” Across the table, Valiant snorts. That night they send Noble in with the wine. “Be sweet,” they tell her. “He might have children your age back home.” He says something; it’s muffled by the door but when Noble comes out she’s crying. Later, when they’re both eating candied strawberries by the pavilion, false hair piled on their heads and their faces powdered bone-white, she says, “He thanked me for the wine.” With a father like theirs, any small act of kindness is enough to melt the younger ones. Mild pushes her toward the floor. “Where’s your prince?” Noble shrugs him off without a second thought. She stuffs another strawberry into her mouth and mumbles, “Something caught my skirt on the way down.” She was at the end of the line. Mild’s stomach curdles. “Maybe there’s a loose brick. Go dance.” They walk back through the forests at dawn. Finger bones clatter and reach for her eyes. Blood on your hands, bones in the earth. The soldier’s snoring in his bed and Mild can’t tell if she’s glad or not. She falls into her own bed, and almost as quickly into a dream. She runs through the forest. She runs even as the ground beneath her turns to muck and and she sinks into the rot, even while vines wrap around her ankles and burst from her throat, she runs until she looks up and sees her sisters swinging from the trees, their eyes blank, the skin sloughing off their bones. She bursts awake, almost sobbing, to find Noble curled beside her. Her sister tosses and moans in her own dream until Mild shakes her awake. “They’re getting worse,” Noble whispers. Mild pulls her up. She herds the younger ones into the garden, where they find the soldier talking to one of the gardeners. Noble charges him, and before Mild knows it he’s chasing them around the garden while her sisters laugh harder than they have in years. A couple hours later, everyone from Clarity to Noble is crowded in his room—even Valiant lingers in the doorway. Mild can’t help stopping herself. He’s telling them stories of a faraway country where she’s sure he’s never been. Mild keeps one eye on him, and one eye on Constance as she rifles through the soldier’s shabby trunk. Midway through a story about shipwrecks and sirens she lifts up a ragged cloak. “Where did you find this?” “It’s a gift,” he says, reaching for it. “And old woman gave it to me.” Constance hands it over, then wipes her fingers on her skirt. “She must have had precious little to give.” Mild glares at her. “Hush.” This time Verity brings him the wine. “Why don’t you do it?” she grumbles to Mild. “He only has eyes for you.” When she stumbled in the garden he reached out and caught her, trying to be gentle but not quite managing it, so for a minute Mild could imagine she was bird-boned and golden-haired, soft as goose down. She is soft, but in a different way altogether. More pudding than goose down. Muck sucks at her shoes as she walks through the forest. She hears footsteps behind them, eyes on her back. She turns in time to hear someone scream. It’s Joy. Shoots —pale, branching like veins—bind her in place. Mild slaps them and they shrink away, but not fast enough. Not nearly fast enough. “What do they want?” Joy asks her. Joy never cries anymore. She doesn’t know. How could she? “They want us to keep dancing,” Mild says. “They want us to stay here.” Shoots curl around her hem. Blood on your hands, bones at your feet. The grounds around the pavilion huddle in a smoky mist. Constance claims she can’t find the library. A prince takes Mild’s hand to dance —it’s like holding hands with a corpse. It’s fading, she thinks. It’s fading but I can’t live anywhere else. I don’t know how. On the way back she hears a snap: a branch breaking. In the morning she hangs over the wash basin, gagging on the sour sludge at the back of her throat. “Only one day left, you poor ugly thing,” Mild tells the turnip-headed doll grinning from Noble’s pillow, at the exact minute that the soldier steps out of his room. She ducks back over the basin. “I don’t like it,” Valiant says after he’s left. “None of the others were this calm.” It’s his last night, so Mild gives in and brings him his goblet of wine. He offers her a chair and a clumsy smile. Mild sits. “You’re a good storyteller,” she says, because she can’t think of anything else to say, not when he’s smiling at her like that. She’d think he was mocking her if his expression wasn’t closer to pity. She hands him the cup. “I didn’t know there were sirens off the Salt Coast.” The soldier laughs again, a deep gravelling sound that shakes Mild to her bones. “There aren’t.” She can’t help but smile. “But then—” he sets the cup on a table, “I’ve never further afield than the midlands, unless you count battlefields. Maybe there are.” Maybe. “You’d better tell the others, if they haven’t found me out already.” “Well,” says Mild. “None of us have traveled even that far.” She thinks of the globes in their cobwebbed schoolroom. “It’s better to see a little bit. Better than nothing at all.” He picks up the goblet. “You’re right.” His expression isn’t pitying anymore. It might be admiring. but she has no idea what to do if it is. Mild gets up, turns to the door. She can feel his eyes on her back. “I’m sorry.” Mild rushes out without answering, and Valiant, already buttoning herself into an explosion of royal-blue skirts, calls, “It’s the last night. Have you picked one?” The soldier tries to catch Mild’s eyes in the mirror. “I think I have, if she’ll have me.” Mild looks away. “You’ve slept two nights already,” she says quietly. “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.” It sounds cruel, even to her. Even to Valiant, who waits until he’s back in his room to snap, “You suit each other. Halfway to old and halfway to fat, the both of you.” Mild slips into her oldest, drabbest dress. But before she goes she takes the turnip doll off Noble’s bed and stuffs it into her pocket. Maybe, even then, they know it’s their last night. Mild’s boat rides low in the water, even worse than usual. She can’t drink, can’t eat; she pushes away her prince and dances until the pavilion fades like mist. As if it were never there. The diamond forest is a glittering smear, but the bones still stand stark in the darkness. They rattle and scream, send out shoots to trip her, but Mild fights through, runs up the stairs and through the door and into the soldier standing by her bed. He reaches out, trying to steady her. She pushes him away. The cloak lies crumpled at his feet. “It was more than a gift,” Constance says behind her. “I knew it.” The king examines the diamond branch. “They’re silly girls,” he says, without looking up. “There’s no helping them. Take your pick, if you still wish to have one.” Valiant shouts. Noble cries. The soldier looks at Mild, who can do nothing at all. “I won’t take an unwilling wife.” She doesn’t answer. She watches her father fingering the diamonds, and she realizes--she always knew, but she’s never realized—that’s it’s real. All of it. She feels a yank on her arm and looks down. “Don’t go.” Noble sobs. “Don’t leave us!” The hall around them seems to fill, dark and echoing like a tomb. Mild looks back up. I never killed anybody. Wild, ghostly music fills the air. They step forward as if they’ve been there all along—dead princes, ready to pull them into a dance that will never end. There’s no escape. But there’s always an escape. Mild shoves her sister away and runs. She locks their bedroom door, screams, “OUT! Stay out!” when she hears them pounding. She knocks on her bedpost until the stairs sink down into the dark. The forest is waiting for her. Blood at your hands, blood at your feet. The bones moan and sigh and pull her to them. Finger bones twine through her hair, pull handfuls out by the roots. She screams until they force apart her lips and work down her throat. She tastes blood, feels cold flesh. Take me. Take me, but not them, not them, take me. She lets their pain and anger break over her. Somehow, she feels the soldier’s doll, still nestled in her pocket. Mild gathers all the force of her dreaming, all her anger, her wishes and hopes and fears, and feels for the door. Closes it. Take me. Her sisters are shouting. She staggers to her feet and opens the door. Valiant flies at her. “What did you do?” “It’s gone.” Her voice is barely a whisper. “What?” “I closed the door.” They all fall on her then, Noble, Silence, Verity, Wit, and Willingness; Amity, Plenty, Clarity, Joy, and Constance. All except Valiant, who watches as Mild kisses Noble and Constance and tells Verity to stop knocking; it’s not coming back. “You know we’d follow you anywhere,” she says. Mild kisses her cheek. “You followed me down there, didn’t you?” “I’ve never been much in this world,” she tells him, “but I’m tired of dream ones.” “I thought you might be.” The doll’s still nestled in her pocket. “Wherever I go, my sisters stay with me.” He nods, and looks at her in a way no man has before —as if she’s beautiful, and worthy, but more than that, capable. Mild takes his hand. They’ve seen so little, but together they can learn. She’ll use her dreams for more than spinning worlds beneath floors; he’ll help her build a better kingdom. The dead voices will never truly leave her, but in time they’ll fade. Her sisters will always be by her side. And they’ll never walk through the forest of bones again.

#Unreal #Fiction #Bones #Forest #Princes #Folklore #Fairytales

Visit our shop and subscribe. Sponsor us. Submit and become a contributor. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

CommentsComments are closed.

|