|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

For Something of Summer

By Samantha Shanley

QuailBellMagazine.com

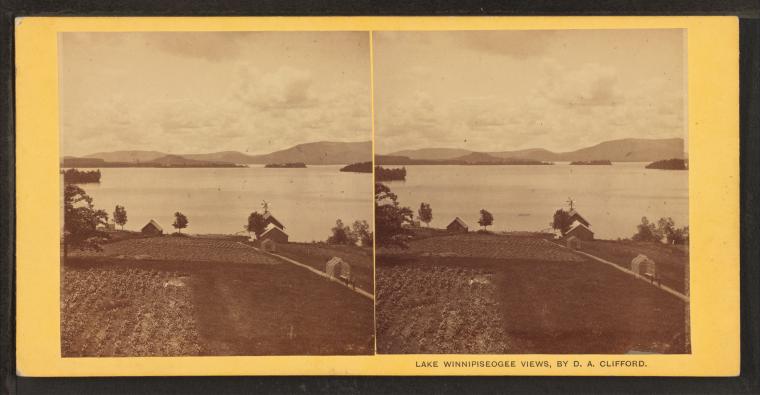

As we did once each summer, my sister and I ventured out from our beloved island retreat on Lake Winnipesaukee to visit the Fisken house on the mainland, where as children, we had often spent afternoons visiting. The house was old and treasured enough to have been given a proper name—Fairhaven. It wasn’t mine, but I had adored that lovely waterside cottage since I was a girl.

When we arrived, the air outside was thick and damp. We tied our boat to the dock and climbed the rustic steps from the waterfront. My three children scuttled up the path ahead of us like insects articulating on tarsus and tibia. My sister carried her baby, clutching him under her arm like a pocket book. We stepped over golden pine needles, brittle from the summer sun, toward the wide porch where a pair of woven rockers waited as always, overlooking the lake. The sun began to shine, breaking into the misty morning. I stilled my breath, as if trying not to frighten off a younger version of myself that might be wandering the grounds, longing for something she couldn’t have. Mrs. Fisken sat in her bedroom, which her family had set up with her things: a small bed with a faded quilt, a nightstand with a water pitcher, and three shelves full of worn and cherished books. It was an enviable spot, directly off the porch with a view like a watercolor through the wavy glass windowpanes, over the low bush blueberries, and down to the rocky shore. When we entered her room, Mrs. Fisken gasped in delightful surprise as she does when anyone appears; she flung her hands out to her sides, letting them fall, fingers spread, like trailing stardust. I leaned in to kiss her. She asked after my grandfather, who for many years before my grandmother’s death had owned a house just down the road—that was the house we had stayed in as children before our parents built their own. Mrs. Fisken marveled that she and my grandfather had both reached their early nineties without issue, and then she turned to greet my children. My youngest stepped forward and told her he was wearing a hat—toddlers are masters of the obvious. My older son gave a short and shy wave, but my eight-year old daughter sat down in a chair thoughtfully, settling in as I once did, her skin browned from weeks of bathing in sunshine and lake water. Mrs. Fisken twinkled for a few minutes, asking questions and lingering on my daughter’s replies before encouraging us to go outside and enjoy the air, and so we did. I pushed open the screen door and found her grandson, an old friend, standing on the porch steps. “Is the boat in the water?” I asked, motioning toward the boathouse where the antique wooden Laker was kept. He shook his head, no. “We’re selling it,” he said smiling and softening, as if delivering an apology. “But why?” I gaped, jamming my sunglasses back down to the bridge of my nose as my eyes welled up. Despite its recent rebuild, he explained, dealing with a cantankerous boat engine was simply too much for Mrs. Fisken now. I slipped inside the boathouse and found the Laker hovering over the water, slung in two thick canvas straps like an infant cradled in her father’s hands. While the cottage at Fairhaven was an intimate thing, belonging squarely to another family, that boat had carried me into the waters I knew and loved well, waters in which I imagined the particles of anyone brave enough to swim in its flow remained as collective, muculent scum, ever clinging to the craggy lake bottom like sodden household dust. When I was young, I would watch Mrs. Fisken start the boat’s engine by turning a small brass lever attached to the middle of the wheel. On afternoons when the weather was fine, she would set out for a ride, steering boldly around the islands and great clusters of granite slabs that rose out of the flashing deep, her grand, gurgling craft churning out an elegant wake. Behind her, I would sit in the open hull among her grandchildren on fanned-back wicker chairs with leather seat pads, waving to people in other boats who would yield to watch us pass. The bow was mounted with a red flag, like a passport of sorts, offering me passage into my dramatic girlhood fantasies, in which I was important enough to be driven some place. The flag was stitched with an “F” for Fairhaven, Fisken, and a time nearly forgotten. That such a time and its leftover things could not be mine evoked in me an ardency that I desperately wanted to feel. I loved my grandparents and their house set back on a reedy beach down the cove from Fairhaven, but their rust-colored ranch was stocked with withering mid-century relics, triggering in me neither nostalgia nor yen, but a prudish distaste for the smell of splintering lacquer. A caramel carpet slithered up the stairs from the basement and held the odor of mildew; on the sideboard stood the body of a stony-eyed owl, preserved beneath a glass cloche; the kitchen shelves were stacked with melamine dinnerware, each piece trimmed in burlap. The mugs from this set had split with age and the cracks inside them were stained with coffee such that they resembled hollow, rotten teeth. When I was fourteen and Mrs. Fisken’s grandson asked me out to a movie, I said yes. We drove fifteen miles in his grandmother’s Volkswagen to watch a film that neither of us cared to see. On the way home in the dark, he struggled to put the standard transmission in gear, so I offered to drive: I reasoned brazenly that Mrs. Fisken wouldn’t mind. We drove along hilly roads lit by the dim orange glow of the occasional street lamp. We reached my grandparents’ driveway where gravel pieces popped loudly from beneath the tires as the car staggered to a stop. I flushed, the adventure complete, the thrill of airy youth mounting within me. He kissed me under the buggy porch light and again while seated on my grandmother’s gold polyester sofa, which wrapped around the living room in a dramatic letter J. The realization that he and I were not meant to be would nag at me longer than it should have; we loved many of the same things—his grandmother and her childhood cottage, the old boat, our lake. I was too young then to call by name my verdant longing for some kind of wonderful thing—a person, a feeling, a cause, a dream—but I could feel it there, taking hold within me like a patch of tender cushion moss. Standing at Fairhaven as a grown woman with my children at my side, I fell again into hopeful musing, what for a long afternoon in that shaded wood, sipping lemonade while someone baked savory bread in the antique kitchen. There was still beauty in that reverie, that old agent of desire for whatever was lovely. I took my children’s hands and turned back toward the house. We walked through the parlor, past a mantle holding antique mirrors and wooden ships, up through secret passageways between bedroom closets and painted pine floors. A tube of shaving cream and a tortoise shell brush lay on a dresser against a papered wall. A suitcase spilled its contents under a window. Behind a door, a nightgown hung loosely on a wire. Although these were not our things, we were not looking for ourselves or for the familiar. We continued up to the base of the hand-cut pine stairs that rose sharply out of the attic into a windowed cupola, nestled high among the wispy evergreens. A small card was tacked to the railing, announcing a gentle rule: “Only two people at a time on the stairs, please!” The “two” had been crossed out and replaced with “one,” so my daughter climbed up alone for a brief glance out and beyond before stepping gingerly back down. When it was time to leave, we meandered down the path to the dock, boarded our boat, and retrieved our ropes from the sturdy posts. Suddenly, my daughter clasped her hands beneath her chin and leaned out the stern. “Mom, I wish this were our house!” she said, calling back to Fairhaven and our friends who stood, waving us off the dock. “I know exactly what you mean,” I replied softly, smiling back at her. In some small way, a thing does belong to any person who loves it, especially in summer, when the delight of possibility reigns. Although she knew yet nothing of all that, like me, my daughter had collected the cottage as she might a smooth stone—a hope in her pocket, a yearning in her heart.

#Real #Essay #SummerNostalgia #LakeWinnipesaukee #Fisken #Island #Boats #Generations

Visit our shop and subscribe. Sponsor us. Submit and become a contributor. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

CommentsComments are closed.

|

|