|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

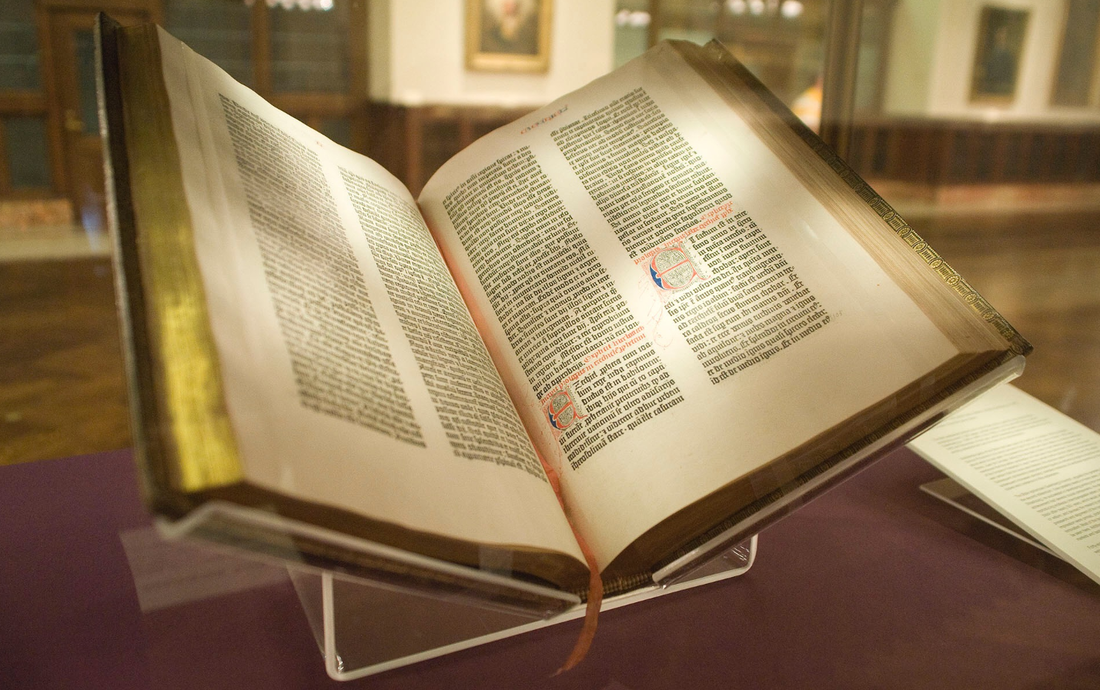

Smelling Old Books While Reading E-BooksWhen I was about fourteen, my eye disease stole my central vision and left me unable to read normal print. Books handed down from parents and grandparents--Treasure Island and Jane Eyre and (my favorite when I was a kid) a collection of Poe Tales--were suddenly reduced to the physical sensations of touch and smell, traces of what I had been, a voracious sighted reader. You may understand then, dear reader, how wonderful the ubiquity of e-books is for me and so many other blind readers. Until recently, obtaining accessible books relied on a handful of not great alternatives—braille, talking book, scanning into a computer—all of which took a lot of time and money to produce. This meant that when and how many published books were made accessible was quite limited and created a huge disparity between sighted and blind readers. Perhaps you may also understand how difficult it is to hear backlash from readers, writers and publishers who take delight in railing against e-books. Last December I read a Publishers Weekly article called Bill Henderson Marks 40 Years of the Pushcart Prize in which I found his blithely naïve reason for not publishing a digital version of the acclaimed anthology: “'in the future, anyone can read it without using a battery,'” to which I cry, "Not anyone!" I generally don't like to come off as a prickly blind person, so I stewed in the implications of such a statement for nearly six months. Then I had an unfortunate encounter with a Guardian opinion piece called Books are Back. Only the Technodazzled Thought They Would Go Away, which opens with this hook: "The hysterical cheerleaders of the e-book failed to account for human experience, and publishers blindly followed suit. But the novelty has worn off" Apparently reading an e-book is somehow not part of human experience, so that, for the Guardian author, only his way of reading—holding a print book to his eyes--is real: "Virtual books, like virtual holidays or virtual relationships, are not real. People want a break from another damned screen." To which I say, "E-books are accessible books and if you want to deny them reality, try poking out your eyeballs! Just kidding. But seriously, for me, e-books are not virtual; they are real, while bookshops with their physical books are virtual, or nearly so; they do smell nice. If the Pushcart article had not hit me first, I likely would have dismissed the Guardian article as tawdry comment-pandering, inflammatory and beneath my notice. However, I do think the problem is systemic, particularly in the highfalutin literary fiction world (less so in genre fiction) where, for example, many of the acclaimed literary journals do not publish electronic versions. Resistance to e-books is an easy way to maintain a rarified air. The biggest problem I have with all this is the idea that e-books must necessarily push out physical books, or vice versa--why can't we all live together? Readers of all stripes should have the choice to read however they please, and frankly it costs next to nothing for publishers to make e-books available at the same time as they print on paper--perhaps this is really the problem. E-books are so easy and cheap to produce that for those who cannot extricate value from cost, they must be worthless, as if putting Plato's Republic, Ulysses, or the King James Bible into an e-book form makes them less difficult to read or less important culturally. Though I cannot understand another's intolerance for e-books, which for me, and many others, revolutionized the accessibility and immediacy of countless works, I can understand the fetish for books, with the fresh cut paper and ink smell of new books and the grassy vanilla mustiness of old ones. The sense of smell, unlike the other four senses, has a direct pathway to the part of our brain responsible for the processing of emotions and memories. As V. S. Ramachandran puts it in Phantoms of the Brain (which is strangely available as an Audible but not Kindle edition), "[Smell] is in fact directly wired to the limbic system, going straight to the amygdala (an almond-shaped structure that serves as a gateway into the limbic system). This is hardly surprising given that in lower mammals, smell is intimately linked with emotion, territorial behavior, aggression and sexuality." Smell then feels more primitive and embedded with our deepest emotions and beliefs. Perhaps this is one reason some physical-book lovers are so intolerant. Perhaps also, this offers a method of approach... To fill the olfactory void left by an e-reader, allow me to introduce you to book-scented products! As the author of 30 Book-Scented Perfumes and Candles puts it, "Any of the items listed below can be a perfect gift for anyone who tasted the convenience of reading on the Kindle, Kobo, or Nook, but will never forget (and doesn’t want to) the addictive smell of the old good books from childhood." As I write, I'm burning Oxford Library, a candle made by Frostbeard. Though my choice was in no small part dictated by economics (some of the book Scented products in the list are pretty darn pricey), I must admit to being influenced by this charming claim: "You’ll dream of sliding ladders, spiral staircases and leather-bound books when you curl up with a novel and this seductive, earthy aroma." According to their Etsy page, the Oxford Library scent is composed of oakmoss, amber, sandalwood and leather. Curious to know more about the lovely smells of Oxford, I looked them up in Perfumes: The A-Z Guide, and found that oakmoss signifies, "Different species of mosses from which are extracted dry, bitter-smelling materials essential to chypre fragrances," and amber is "A blend of fragrant resins, such as styrax, benzoin, and cistus labdanum, traditional to the Middle East," and that sandalwood, with its long history in perfumery, provides some of the "main chemical building blocks of fragrance" and is one of a few materials "found in almost every composition," and that the smell of leather is "characterized by bitter-smelling isoquinolines or smoky-smelling rectified birch tar, to replicate the smell of the tanning chemicals used to prepare leather." All these combine to create an aroma of masculine luxury, seeming to represent the dusty men as well as the dusty books of Oxford. The smell suggests at once the Platonic ideal of "Father" and a first edition of Wuthering Heights—not bad for a few bucks! So where does the actual smell of old books come from? Perhaps it is obvious, but much of the glorious smell indicates degradation. As reported by The Telegraph in The Smell of Old Books Analyzed by Scientists, a team of scientists developed a "sniff test" for old books to determine their level of endangerment: "Matija Strlic, a chemist at University College London, and lead author of the study, and her team note that the well-known musty smell of an old book, as readers leaf through the pages, is the result of hundreds of so-called volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released into the air from the paper." Certain of these chemical compounds can be used as a warning sign for libraries: "The scientists identified 15 VOCs that seem good candidates as markers to track the degradation of paper in order to optimize their preservation." Of course, one of the simplest ways to preserve a book is to minimize handling, and the easiest way to minimize handling is to digitize the books! Yep, I'm back on my soapbox: digitized books—searchable e-texts as well as facsimiles, help preserve the originals while simultaneously making the works available to people who may not be able to travel to the Bodleian Library at Oxford! In other words, accessibility is not just about blind people but also about the general reading public. Take for example HathiTrust, whose tagline is, "Welcome to the Shared Digital Future," and whose mission is to work with institutions around the world to "ensure that the cultural record is preserved and accessible long into the future." It may be this very accessibility that really sticks in the craw of a person like our Guardian author, as if the means of dissemination has anything to do with people taking the time to read the books in question. For those of his ilk, the physical manifestations of books are meant to be treasured and amassed: "A book is a shelf, a wall, a home," oh my! Wonderful as they are, a personal library does not a reader make. Spending time and energy reading, having a mind-meld with an author—perhaps across centuries--should be the primary endeavor, and the acquisition of a beautiful edition a distant second, a luxury for those with the money and space to collect such things. Speaking of luxury, when things get a little less tight in the Astoria Bat Cave, I may have to invest in a fragrance called Paper Passion, which invokes the smell of a freshly cracked new book. Then, whenever I feel blue about a snooty publisher or author neglecting to publish an electronic version of this book or that, I will spritz myself. And, while I deliberate whether or not buying the physical book, and spending the requisite hours scanning, is worth it. I will sniff my book-scented skin and be grateful to live in the digital age, hopeful that accessibility will win out in the end. #Real #Column #DistillMyHeart #OldBooks #BookSmell #BlindReader Visit our shop and subscribe. Sponsor us. Submit and become a contributor. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

CommentsComments are closed.

|

|