|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

The Spirit of St-Germain Elderflower Liqueur

Last month, there was "sad news in the spirits world" when it was reported by Eater.com and countless other food and beverage blogs that Robert Cooper, the founder of the wildly popular St-Germain elderflower liqueur, died suddenly at the age of 39.

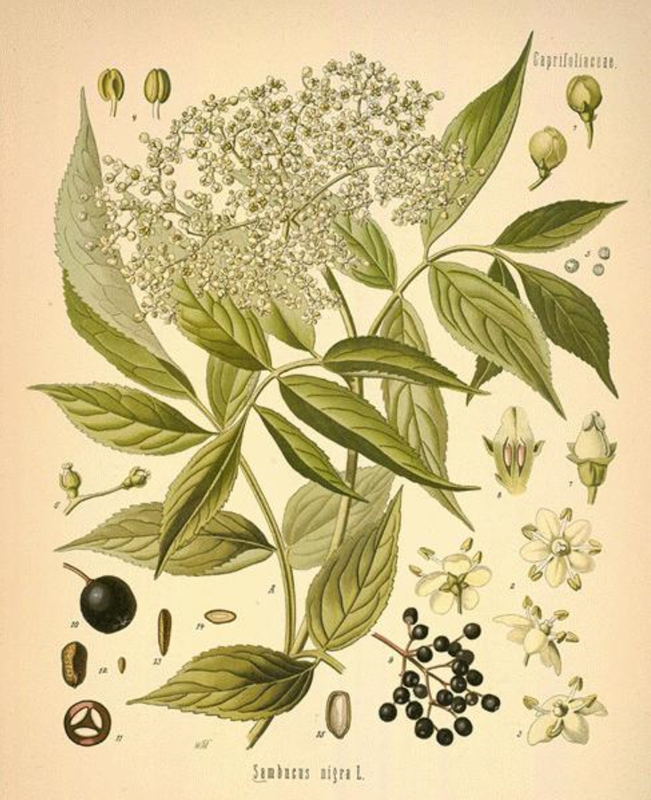

Cooper was born into the booze business, but struck out on his own when his idea to make an elderflower liqueur (like those he'd encountered in London) was dismissed by his father. His father had cause to regret his indifference since, as NY Times put it, "St-Germain, packaged in a striking Art Deco bottle, landed like a thunderclap in the then-burgeoning cocktail world." Cooper's inventive marketing (which highlighted bartender's ingenuity) and the distinct flavor of St-Germain (often referred to as "bartender's ketchup") helped boost the mixology trend that has proved so interesting in the past decade or so, pushing a creativity in cocktail-making that goes hand in hand with this millennium's DIY zeitgeist. With craft spirits and handmade bitters, bartenders armed with droppers and spritzers, today's mixology far surpasses anything seen at the bar since prohibition. Although, as with all trends, there is an annoyance factor, I, for one, am excited by the explicit interrelations of booze and botanicals—that is, after all, what this column is all about! St. Germain was sold to Bacardi in 2012, but in its press release, they stressed that the artisanal methods would remain unchanged. They present the charming picture of free-lance pickers who for 4-6 weeks in the late spring harvest the delicate flowers and bring them to collecting stations "where harvesters are paid by the kilo for their flowers, often using specially rigged bicycles to carry them." There they are quickly macerated to preserve the "captivating fresh flavor, reminiscent of tropical fruits, pear and citrus with a hint of honeysuckle." To be honest, I was surprised by the tropical fruitiness of St-Germain because my first experience with elderflower was as a hydrosol from Stillpoint aromatics and it was, as I mentioned in my previous article on The Botanist Gin, like chocolate if chocolate was indigo velvet. So completely different from St-Germain's bright fuchsia nectar. Just goes to show you that different methods can produce different flavors from the same plant. Also, as I don't drink liqueur (except when I visit my mom and pour a little Kahlúa in my morning coffee), I'd not prepared myself for the sweetness, which was dumb because, as I learned from a quick Google search, sugar is one of liqueur's key ingredients. In his comprehensive book, Homemade Liqueurs and Infused Spirits, Andrew Schloss explains the role sugar plays, "The more sugar syrup added to the alcohol base, the silkier the mouthfeel of the finished liqueur will be. This viscosity slows down the flow of the liqueur across your palate, which allows the liqueur to linger in your mouth longer, thereby giving your taste buds and olfactory receptors more time to pick up flavor, which is why sweeter liquids taste more intense than thinner ones." It turns out that liqueurs are composed of three elements a base spirit, one or more flavoring agents which have been macerated in that spirit, and sugar. That's it! Maceration or infusion--the terms are used interchangeably--refer to two sides of the same process: one macerates a solid in liquid in order to soften it and extract its flavors and aromas, while one infuses the liquid with these aromatic and flavoring compounds. If the process of maceration/infusion sounds familiar to herbal and booze enthusiasts alike, that is because, although one generally buys tinctures at the health food store and bitters with their booze, they share a common origin. As Brad Thomas Parsons writes in his book Bitters, "Using bitter herbs, barks, and botanicals for medicinal purposes dates back centuries, and versions of some of these potable elixirs are still around today, like the herbal liqueur Chartreuse, which was first made in 1737 by Carthusian monks who based their recipe on an ancient elixir..." Parsons goes on to explain that while bitters are composed of many flavoring agents--bark, peel, herbs, flowers, etc.--and are also often diluted and mixed with sugar, tinctures are a "single-flavor infusion" and do not contain anything other than the chemical constituents extracted from the plant material and a high-proof spirit. Hence, Chartreuse is sometimes referred to as a bitters based liqueur, while St Germain can be said to have tincture of elderflower at its heart. I've not been able to find anything about how Cooper came to call his elderflower liqueur St-Germain, but I like to think that it was named after the Parisian neighborhood and Medieval Benedictine abbey Saint-Germain-Des-Prés, as a nod to the spiritual roots of his quintessence of elderflower. Quintessence is a term taken from Aristotelian natural philosophy and used by alchemist-monks such as the 14th-century John of Rupescissa, to describe spirit of wine, (brandy). In his book The Secrets of Alchemy Principe writes, "John considers this "burning water" the "fifth essence" of the wine, its quinta essentia in Latin." Since John was interested in the health of the body as well as the soul, he appreciated alcohol's magical ability to extract and preserve the qualities of medicinal herbs, thus transmuting the putrefying-prone plant material into a quintessence which might last indefinitely. Principe writes, "the central chymical operation of distillation—the separation of a pure, volatile (that is, "spiritual") substance from the crasser, baser components of a mixture--appears frequently as a trope in devotional literature." To illustrate the point, he quotes the bishop Jean-Pierre Camus (1584-1652): "Let us put all our good and bad thoughts, affections, passions, vices, and virtues all mixed together into the alembic of our understanding. Place it then upon the memory and recollection of the eternal fire as if upon a furnace, and we shall see some marvelous subtle effects. This fiery cogitation will separate the confused elements, the hullabaloo of ambition, the earth of greed and lust, the winds of vanity, the waters of covetousness, the air of presumptions. It will dissipate all these follies, destroy the dregs and lees of a thousand earthly desires, in order to extract beautiful and completely heavenly conceptions from them ... it will dissolve all our vices and sins, and extract from our souls a quintessence of piety and devotion..." It is no coincidence then, that our word for high-proof booze is spirit. Perhaps it also seems less strange, now that we recognize this connection in the Early Modern imagination, that monks were responsible for the first liqueurs. But what about this elderflower? Though we may imagine them as ancient tree beings, akin to Ents, the etymology of the English word elder derives from its more humble use as kindling. In A Modern Herbal (1931), Mrs. M. Grieve writes: "The word 'Elder' comes from the Anglo-Saxon word aeld. In Anglo-Saxon days we find the tree called Eldrun, which becomes Hyldor and Hyllantree in the fourteenth century. One of its names in modern German—Hollunder—is clearly derived from the same origin. In Low-Saxon, the name appears as Ellhorn. Aeld meant 'fire,' the hollow stems of the young branches having been used for blowing up a fire..." Elder is often called the Medicine Chest of the common people. Grieve attributes this epithet to Ettmüller (a 17th-century German physician and botanist), and describes the many medicinal uses of the plant, for example: "Elderberry Wine has a curative power of established repute as a remedy, taken hot, at night, for promoting perspiration in the early stages of severe catarrh, accompanied by shivering, sore throat, etc. Like Elderflower Tea, it is one of the best preventives known against the advance of influenza and the ill effects of a chill." Grieve also tells how, "In Denmark we come across the old belief that he who stood under an Elder tree on Midsummer Eve would see the King of Fairyland ride by, attended by all his retinue." And if that's not enough, Grieve goes on to give a recipe of our great-grandmothers beauty secret: a toner made from a strong tea of elderflowers mixed with "rectified spirits"—a happy addition to every lady's toilet! "She relied on this to keep her skin fair and white and free from blemishes, and it has not lost its reputation." She concludes: "A well-known French doctor has stated that he considers it a fine aid in the bath in cases of irritability of the skin and nerves." All this was enough to inspire me to procure some dried elderflowers from the beautiful East Village herb shop Flower Power and, in parting, I share with you my recipe for a magical elderflower moment:

#Real #Essay #DistillMyHeart #Column #Elderflower #Spirits

Visit our shop and subscribe. Sponsor us. Submit and become a contributor. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

CommentsComments are closed.

|

|