|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

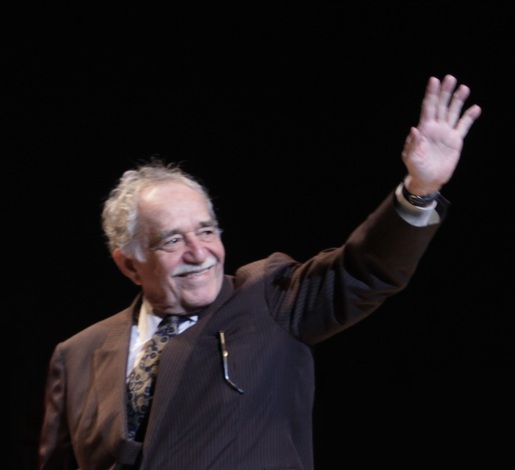

Meditations on Mi Gabito Writing about this will take all of my energy, as Gabriel García Márquez (nay, let me call him Gabo, or Gabito, for should writing be my life then he is my father, for he engendered and birthed into me taste, style, passion, love) has smitten me. It’s a long relationship, one of embarrassment, tragedy, mourning (the Spanish word, luto, captures more musically the weight of the term), love, and cholera. My first foray into the world of Macondo came from his iconic story, “The Handsomest Drowned Man,” and I abhorred every minute of it. To this young David, a man wrapped in naiveté, one who considered only science fiction and fantasy to be inventive and good uses of art, who asked for dystopian mechanics or nothing, the folkloric tale of a town swept off its feet at a dashing young drowned man left me nothing. An Orange County kid can’t even think of the word folkloric without frothing irony, the concept bringing about only the kitsch a suburbanite can expect from native customs. My only brushes with such ways of thinking came from the postmodern, hyperreal world of the California I-15, where Baker’s world-largest thermometer stands. But even this is simulacrum of small town, a place pretending to be kitschy and quaint for the sake of tourist revenue. It’s attempted folklore, diametrically opposed to Gabo’s tale. Of course, it wasn’t till my personal boom at age fifteen, when I revisited the story of Esteban and his swollen beauty, that I understood the mere attempts at folkishness that plague Southern California. For those unaware of the history of Orange County, we were founded by a Klan member, there’s a church on every block, and our one claim to fame is giving birth to Richard Nixon in a little home in Yorba Linda. We attempt to look the part of Nixon’s silent majority, folksy, conservative, Republican, church-goer. When the Oakies came they settled two places, the Valley and Orange County, and we collectively long to be Midwestern, to be folklore. Orange County has no more oranges, but we embrace this pastoral identity, turning a long dead industry into our symbol of greatness. A brush with pastoralism, sans kitsch, could only lead to a disaster of identity, an engendering of otherness, and a deconstruction of previously held ideals. At fifteen, I made it big. At the end of my life, I’ll be able to point to most anything that happened in my life and trace it, like chisel in a rock face, back to that glorious year. To hear nostalgia uttered forth by an eighteen year old might declare itself camp and melodrama, but that year I was first published, a limerick in a little zine. That year I made the first poem I consider to be “art,” about three friends and their terrible landlady. I had a first date. I met my best friend. The landmarks of life all came at once, in that beautiful year. But above all this, I acquired something immutable, a feeling, not an experience, a feeling called taste. Taste, while arguably the ultimate tool of modernist pretension, has given me everything. Taste in film, in magazine, in games, in philosophers has imbued me with the drive that makes me create. And that taste came almost singlehandedly from Gabo. Prior to year fifteen, I hated Joyce’s “Araby” and Carver’s “Cathedral.” My creative writing courses had tried to give me taste, or at least loan it to me for the time being, but I had refused it, reveling in the superficial (though I would never call it that.) To find taste, one must find passion; taste cannot be borrowed, or loaned, or carefully cultivated, or taught. It presupposes a spontaneity of the self, a sudden desire and draw, one that requires no catalysis to turn reactive. At age fifteen I read One Hundred Years of Solitude. Taste presupposes a criticality. The epic of the Buendias was the first time that criticality percolated within me, that I saw the text no simply as a passive work meant to construct pleasure but as a nuanced, academic text, one that exists within itself and functions within itself. I’ve yet to find somebody who can describe the process of criticality without descending down to pedantry. Analysis, criticality, both exist beyond frigid academia, and to discover this is to embrace taste. During winter break, one night, I finished it, devouring all-but-literally the last one hundred pages, finding the final Buendia and his ultimate incest, his ultimate destruction of his home. Macondo was gone. And so was I. When I revisited “The Handomest Drowned Man” the following week I understood what this folklore meant. I understood the wholeness with which one had to believe magical realism, to embrace some inherent primitivism that wells up within us. The point of that story, all along, had been that this town could achieve a metaphoric salvation by giving up ego and embracing solely pathos. The reader experiences an issue with this narrative, with the murky otherness of someone standing outside of the planet and peering in, and therefore undergoes the same journey of the inhabitants of Esteban’s island, seeing first only the bloated and sludge covered figure of Esteban and then, with a little work, removing these trapping and see Esteban in all his glory. On April 17, the New York Times released their obituary on Gabito. Two in fact, a political retrospective, and an aesthetic one. The political one was well researched, discussing his communist leanings, his relationship with Castro. It was lucid, informative, commendable. But the aesthetic one found fault. It rehashed the old clichés, Gabo’s legacy with Borges, Joyce, and Faulkner, and the famed “he found the mystical in the mundane and the familiar in the fantastic.” And I take issue with this. The run-of-the-mill sci-fi writer can find the magical or the mystical in the familiar or the novel. Even this writer’s analysis on the politics of his aesthetics, that of depicting the rewriting of Latin American history, shows a simplistic interpretation of this monumental author. The irony of course, is that the death of a magical realist would present the same mundane and shallow analyses. These critiques otherize Gabo, turn him into a man from a mystical land. Gabo challenges all to remove this artifice, to, like those islanders, shed off the “murk” that surrounds Esteban.The erudite critic might declare that Gabo embraces artifice, constructing a new narrative for the Americas as Rivera or the Brazilian Five did for their countries, this locative thesis of historical erasure and rewriting adopts antithetical positions. The idea of ironic artifice comes from postmodernism, but the declaration of a new racial background, in particular compared with Mexico’s great muralist, reeks of modernism. Furthermore, to say that Gabo invented magical realism in order to erase the lasting presence of neocolonialism excludes his universal interpretation, and should he find such a vocal proponent in an Orange County kid, a place that has never erased the names of dead factory workers or watched the endless time of eternity come to an end, then such an interpretation cannot hold. Rather, his works, to me, proclaim a pure otherness to the world, declaring that the world itself is the other, not its inhabitants. Here Gabo differs from the Brazilian Five, who embraced their otherness, proclaiming the French “negritude” as the best mode of existence. Gabo does not celebrate his otherness. Instead, he creates a world where everyone is the other, where the reader is the other. The reader feels an intense discomfort, examining a world so real yet so distant from his own, a world without cities, with prophecies, with the inexorable memory of Colonel Aureliano Buendia haunting every page. This discomfort simulates otherness. It engenders a sense in the reader that they exist in the wrong world, or that they see the world incorrectly, or that they exist as the other. It turns the reader into the artifice, into the fake one, into the one outside of the real. Gabo does not erase history, he does not reconstruct a new propaganda to combat that of the Frutera. He is not Neruda, who embraces the psychological realism of the Magellanic Heart or the simple myth of “La United Fruit Company.” Nor is he Cortazar, whose “Hopscotch” revels in ergodicity and neomodernism (though, perhaps, an analogue can be found to Cortazar’s “Axolotl” whose subject is pure otherness and whose surrealist construction may even induce otherness into the reader.) Gabo constructs a world of pure other truth, one so true that it shows off the inherently dissembled artifice of the reader, engendering a subversive otherness into him. Maybe this comes down the Bloom’s “anxiety of influence,” and I am misinterpreting an idol in order to attain something original. It’s hard to say. So it goes. But I believe that the physical act of reading Gabo turns the reader into the work of fiction. In “The Autumn of the Patriarch,” the reader cannot possibly have the immense psychology of the Patriarch. Nor can one say that they exist more than Macondo and its flying carpet, or that they have some sort of higher ontology that the titular Colonel. These places and people truly exist, existing not in the same hyperrealism of the California I-15 but in a new type of hyperrealism that makes the reader the unreal. It proclaims a universal otherness, one where the race condemned to One Hundred Years of Solitude is the reader himself. Gabo does dwell on depictions of otherness in such works as No One Writes to the Colonel, a work of pure realism. To say that all of his work chooses to depict otherness and artifice is to deny the multitude of styles he adopts. To say that No One Writes to the Colonel is a work of otherness is to preclude The Autumn of the Patriarch from such a title. Gabo could depict, surely, but he could do so much more. I can’t say that I have adored all of his novels, nor can I call myself an expert, having only experienced him through translation. It could be that this error of translation is what has left Leaf Storm unreadable. I adore Love in the Time of Cholera in its first act, where it emulates the lives of Gabo’s grandparents, but even when Juvenal Urbino de la Calle falls from his tree and the true protagonist is revealed a certain kitsch can be seen. While others have glorified its en media res, I find it lacking: Its pastiche of the 19th century novel, while admirable, forgoes the general sense of otherness that permeates his works. Unread are his works in Strange Pilgrims, Memories of my Melancholy Whores, and Living to Tell the Tale. "Living to Tell the Tale: Part One" of his memoir, which will never be accompanied by a second half. As a consolation prize, the week before his death, an exhaustive biography was written, detailing his long and winding life, and when I saw it on the bookshelves of The Last Bookstore I wondered if it was a premonition. I took a weekend trip up to Portland with my family, the first time my older sister was out of the picture. For that trip, briefly, I was an oldest child, a magical thing in pursuit of his new power. We went to Powell’s Bookstore, a large independent place that reeks of the Portland spirit. I bought The General in his Labyrinth, the last book by Gabo I have read, and this first half of his memoir. I told myself I could wait on that one. Who would start a story and then end halfway? There were novels to be read. I had just ended my Joyce renaissance, reading all of his prose, and I looked forward to curling up with Shakespeare, whose comedy always reinvigorated me. That night, at the hotel, I got the news that Gabo had stopped writing. 85, older than a 16-year-old can phenomenologically conceive of, and he had developed dementia. Failing health. Dementia ran in my family, and I had run into it at ten when my family went up into the woods to watch over my ailing great grandmother. But I still held hope. I held hope that somehow the perpetual otherness I had felt on that winter’s night would be reborn, and never come to an end. Dementia, after all, to a boy of 16, seems impermanent, intangible, even when he has seen it up close. He hopes for some lucidity. He hopes that the writer, the artist, the maestro, will, through some romanticized ideal break out of the shrouds of his mind and write again. The artist is an artist to the core, believes the sad 16 year old, and surely even when health fails, at the heart of thing Gabo could never stop writing. He had sold things based on lucidity, and surely that could not disappear. By the time I finished The General in his Labyrinth I knew, logically, that it was over. Gabo would not come back. The next year I started reading David Foster Wallace, just as his “This Is Water” speech began making the rounds on the internet. Fosterphillia, in 2013, hit hard, with a biography and many unpublished works rattling the shelves. The Pale King had made it big three years before, but the number of unpublished works now proliferated in the market place. In my backyard I thought about Gabo and how, at some point, they would strip his body down to whatever was marketable. The analogy between body and corpus is intentional, they would take what little bits of literature were left in his care and sell them. Marquezmania, every post-it note he ever wrote in his dementia would be published. Like his eternal patriarch, had he ever written his name down on a post-it note, to assure himself of who he was? Did he remember the voice of his mother? Would each of these stray thoughts be compiled and presented to the Spanish speaking world? I thought about the inevitable, the cyanic conclusion to my hero’s lifetime. In the end, the products of that inevitable Marquezmania would be kitsch, unreal, mundane, everything Gabo stood against. The memoir will remain unread. Never will I open those pages. I will wait diligently until some point in time that it might be finished, that some Quixotic contraption allows the world to be made right again, till Marquez becomes one of those ghosts he loves to write about. These sorts of essays offer the question as to whether a eulogy is for the dead or for the living, for those who survive. Despite the inherent melodrama of this question, it stands: do essays for the dead provide any sort of perspective for anyone, be they hagiographic pieces dedicated to the dead or ponderous affairs that mix disdain and adoration? Or is this even an essay for the dead, since it exists only in my experiences, the privation not of the funerary but of the living, of my experiences in the lens of a single man? Or am I truly assuredly selfish to write this kind of essay, to turn a great man’s death into a springboard for self analysis? These eulogies normally come from close friends, ones who accompanied the author on a book tour and can provide new material for voracious fans. I do not have this material. I never met the man. But should my thesis on Gabo’s distinct brand of otherness hold true, I would argue that this look at myself, this uncovering of my personal and private dissimulations, viewing myself as the subject, as the material, factors into Gabo’s thesis on the world. Sure, it might take a more surfictive approach than his works (though to read One Hundred Years of Solitude and not see Melquiades as a metatextual representation of the author would be impossible) this sort of self-analysis, in which the reader (me) and the author (me) and the subject (me and Gabo) view each other as the other, factors into the general dialogue of postmodernism that Gabo participated in. Because Gabo lived the folkloric life of the other. One of my dear friend’s mother met García Márquez in Colombia, during the '80s, before his super stardom of “Love in the Time of Cholera.” My friend said that Gabo loved her mother because when they first met for she did not recognize him and his fame. This is the only piece of personal anecdote I can say I have about Gabo, itself a second hand story on which I have constructed myself. It is a fiction like any other of Gabo’s, I have constructed my own memories upon it. But this folkloric eschewing of fame, ironically the one piece of original research I can add to this eulogy, shows that Gabo considered himself the other just as much as the reader did. He felt removed from his own fame. He felt alien. And he used his alienation to exact alienation upon his readers, to level the field between author, art, and viewer. He made the reader him, in a way that no author has emulated. He was the godfather to my friend, who moved to America when she was three. She does not remember him, but at some point my hero held her. The American sense of degrees of separation, something truly hyperreal, applies here. I have some sweet nostalgia in the idea of this lingering essence of Gabo left in my friend. Of course, I understand the irony of experiencing Gabo through the blockbuster construction of degrees of separation. This metric, akin to the Bacon Score, could not find itself in pure Macondo. There is no room for artifice in a book of prophecy, no room for lies in Melquiades’ collected works on the Buendias. Such superficiality could not stand in Macondo. But at least Gabo allows us to feel the discomfort of otherness, to embrace ourselves as alien from the magic of this world, to understand the struggles of those marginalized not through a depiction of marginalization but by simulating marginalization within the reader. The other is a perpetual wanderer, and we the readers, when we see Remedios the Beauty blown away on a strong summer breeze, can feel what it is to wander. And maybe this is the backbone of taste, more so than passionate criticality. Maybe taste is akin to empathy, to finding humanity even in the other, even in the mirage-like labyrinth of Gabo’s pure invention. #GabrielGarciaMarquez #Obituary #Literature #Death

CommentsComments are closed.

|

|