|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

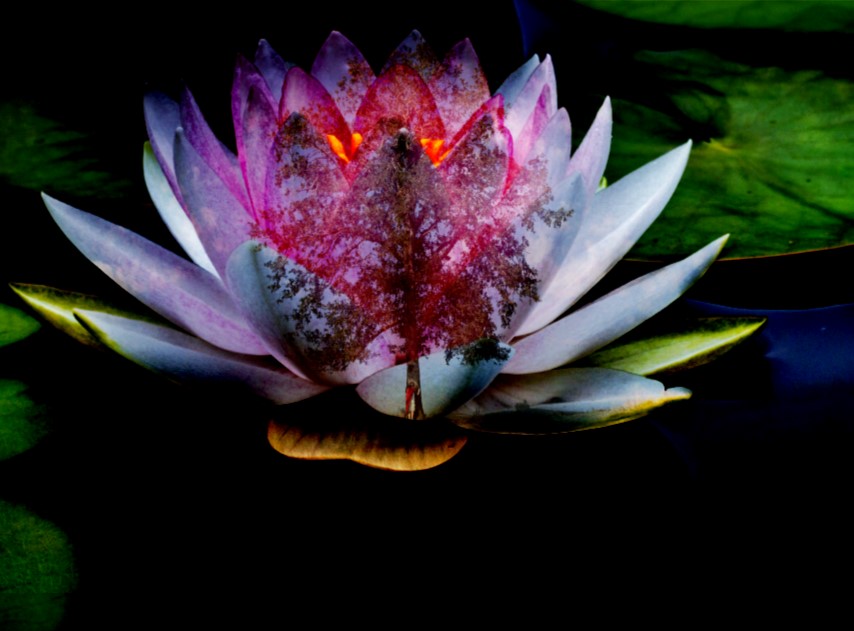

Still, LifeWords, Audio, and Narration by Meriah L. Crawford Image by Gretchen Gales QuailBellMagazine.com *Editor's Note: A previous version of this piece without accompanying audio appeared in Style Magazine. The author wishes to acknowledge and thank Bill Blume, a Richmond-area author who voiced the 911 dispatcher in the audio. Click here to listen to accompanying audio.The woman is lying on the bench, asleep, when I arrive at the North Richmond train station around noon. For some reason, I feel compelled to sit and watch her for a minute or so, until I catch the rhythm of the rise and fall of her side. In spite of the air conditioning, the air is warm and heavy, and I doze for what must be almost two hours. I awake to see the same woman, lying on the same bench -- only now, she’s not breathing. I know in a distant sort of way that I should get up, call for help, do something. But I just sit and look at her, a slight buzzing in my head and a heaviness in all my limbs. I’ve been away from home for just over a week, staying with Aunt Calliope for Uncle Herman’s funeral. Herman was not her husband, and not really my uncle, but he’d been her boyfriend for nearly two decades. He was as much family as any of my other aunts or uncles. The week had been wrenching, hectic and more utterly exhausting than anything I’d ever been through. He was a well-loved man, and I’d had to cope with friends and family crying on my shoulder, telling me their stories and regrets. Everyone assumed that my dry eyes meant I was unmoved, and therefore able to take a share of their sorrow. Truth was, I just preferred to grieve in private, and the extra weight had been almost more than I could bear. I left as soon as I could reasonably go. As soon as Aunt Calli was able to sit through breakfast without sobbing, and remembered to take showers without prodding. Herman had been just 48: not quite young anymore, but nowhere near old, either. Calli had expected to have him with her for another two or three decades at least, and she was angry along with being distraught. I understood, as much as I could, and loved her dearly, but the time I spent with Calli just brought back memories of losing my Lily. It’s been just over a year since my daughter died, her skull fractured in a fall from a tree, and the wounds are still barely scabbed over. This woman, meanwhile — long and skinny, pale and still — lies on the hard wooden bench, dead. She’s wearing a white tank top that shows off her toned arms, and tight tan pants that show off her panty lines. Her low-heeled white sandals rest against thickly callused heels, and her toenails are painted a deep, glossy red. Her shoulder-length brown hair is thinning and looks dry as straw. She possesses only a small canvas handbag with pink satin lining, as far as I can see — though she may have checked some luggage earlier. I wonder if she’s been waiting for a train, or if someone’s coming to pick her up. Or maybe she was just looking for a place to stretch out indoors for a while, to cool down. It’s about 90 degrees outside, with the typical Richmond humidity of midsummer, so that might explain her presence. A man with an Amtrak uniform and a walkie-talkie strides past. For a moment I’m certain that he’ll notice her, but he walks on by with his mind on other matters, the woman as invisible to him as all the other passengers must be. Everyone else is similarly distracted, their minds on their own business: eyes focused on friends, newspapers, cell phones, small children. I see a man in his 40s holding a little girl up to the window as a train comes in: Richmond to Boston, two hours late, hooting and clanking as it eases into the station. The pair reminds me of Uncle Herman and Lily, my own sweet Lily-belle, if only because they’re the right ages, the right genders. I can remember Herman holding Lily like that when she was just 3, as he showed her the cream-colored dairy cows on the neighbor’s farm. He held one big, gnarled hand pressed to her belly to balance her as she leaned out to pet a calf’s head, a look of awe on her face. It strikes me that Lily would never have been caught dead in the girl’s pink, frilly frock, and I wince at the phrase: “caught dead.” I guess that’s what she’d been — caught by death, almost in midstep, without warning. Like Herman. Like the woman on the bench. I reach over and touch my cell phone, clipped to my waistband. If I call 911, the whole station will erupt in a chaos of police, emergency vehicles, complaining witnesses and bystanders, the press. There will be question after question. And, my God, I want to be home again more than anything. I slide my hand back into my pocket, and stare at the patterns of dirt and scratches on the floor. I wonder what Lily would think of my inaction, and I can see her standing beside me in Lake Mayer Park one spring day, looking down at the body of a small puppy who’d clearly been hit by a car, thrown to the side of the road, and died. “Where do you suppose his mommy is?” Lily had asked, trembling. “Won’t she miss him?” “We should leave him,” I told her. “It will be all right.” But she frowned up at me, and I felt a stab of guilt at being caught in so obvious a lie. It wasn’t going to be all right, and she’d known it. It isn’t going to be all right for this woman, either, but there’s nothing I can do to help her. And if I call the police, it will be hours, at least, before I get home again. It might even be a day or more if it goes on long enough. There are only so many trains that go to Savannah -- my final stop — and in just a few hours they’ll close up shop for the night. My train will arrive in less than 15 minutes. I tell myself I can call the station on my cell from the train; they’ll never know it’s me. I can just say the woman seemed sick or something. I can say I was afraid she might be contagious. And then I wonder if she might be. Now that Lily is gone, I don’t have to be brave anymore. I don’t have to pretend it’s OK when I take her to day care every morning, or that I don’t worry when she goes to a friend’s house to play afterwards. I don’t have to make believe she’s safe from perverts and chicken pox and drunk drivers. I don’t have to tell her lies about kittens and goldfish going to heaven, or that she doesn’t have to be afraid of monsters under her bed. Now that she’s gone, I leave the light on in the bathroom at night. I make sure the doors and windows are all locked before the sun sets. And I sleep with a stuffed dinosaur named Snore held tightly in my arms, and dream that Lily’s still with me. A sudden urge comes over me to go over and hold the woman’s hand until help arrives. I wonder if she could have been resuscitated if I’d called soon enough, but her lips were blue by the time I noticed she wasn’t breathing. It must’ve been too late. I’m sure it was. It took me two or three minutes of focused staring just to be sure she wasn’t breathing, and her brain would’ve been quite dead by then. Surely. Twelve minutes before my train is due. A little boy, maybe 3 years old, walks up to the dead woman, reaches his hand out, and touches her nose. “Nathan!” a harsh voice calls. “You get your hiney over here right now, young man!” The boy, fearing the wrath of momma, yanks his hand back and runs over to a large woman with white-blonde hair standing under the arrivals monitor. She grabs his arm and pulls hard, causing him to yelp in pain. She whispers at him — harsh, ugly words — and he starts to cry. They walk outside to wait for the train, the woman standing stiff and arrogant, the little boy’s shoulders hunched and his soul crushed just a little more. I hate her. I wish she was the one lying dead on the bench. I could take Nathan’s hand and sneak him on the train with me. I’d bring him home and teach him to stand up tall, to treat people with respect, to be warm and loving. I’d teach him to think of others before himself. “Do as I say,” I whisper softly, “not as I do.” And I wait. Eight minutes to go. I gather my things and head to the bathroom. Maybe someone else will find her while I’m up. Maybe she’ll wake suddenly, and it will all have been a mistake. Maybe I’ll come out again, and she’ll just be gone. There’s only one stall empty, and someone has peed on the seat. What do people think they’re going to catch by sitting on toilet seats? I hope it ran down her leg. I hope she got toilet paper stuck to her shoe. I hope she finds the dead woman. I wash up, brush my hair, and scowl at the faint wrinkles radiating from the corners of my eyes. I return to my seat. Nothing has changed. Five minutes left, and there’s an announcement. “Uhhhh, folks, we have a slight schedule change up on the board. It’s, uhhhh. Please check the board for the latest schedule changes.” I turn and tilt my head, squinting at the tiny red letters and numbers, and I see that the train going from Richmond to Savannah, my train, is going to be an hour late. I sigh deeply and shake my head. “It’s going to be a very long damn day,” I say aloud, and three people turn and stare. I get up, walk out the front door to the parking lot, where the setting sun imbues the trees and a pair of decrepit train cars with a soft, implausible beauty, and dial 911 on my cell phone. CommentsComments are closed.

|