|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

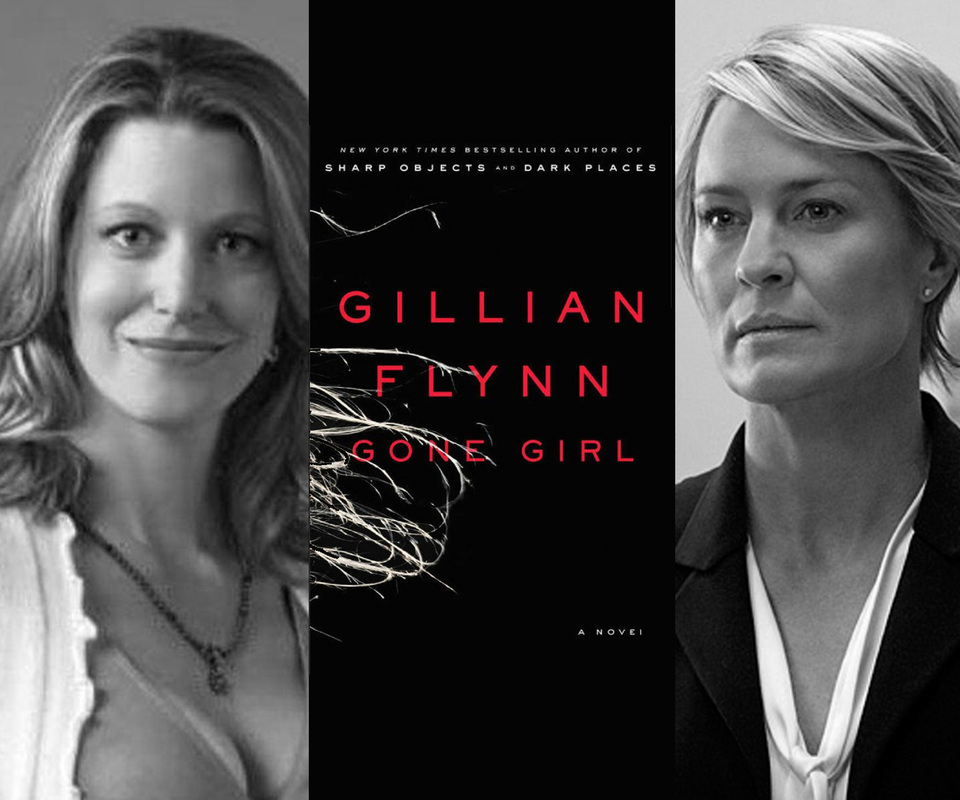

Autonomy, Ruthlessness, and SexualityBy Zack Budryk QuailBellMagazine.com Editor's Note: Spoiler Alerts for Gillian Flynn's Gone Girl, George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, and House of Cards. It’s extremely important to be able to recognize a work as problematic, even if it’s something you enjoy. With that in mind, fiction featuring the femme fatale archetype tends to have a woman problem. The noir genre, which codified the trope, has a deeply misogynistic streak running through it, as does the femme fatale character itself. A woman who uses sex and deception is presented as exponentially worse than a man (or a woman, for that matter) who relies on physical coercion. I’ve never believed the solution to problematic plot devices was to stop using it altogether, though; it can be far more instructive—and entertaining—to deconstruct it. Femmes fatales are no exception, and recent television and literature has given us a new class of characters that coexist as amoral, antagonistic characters and as vessels for solid points about feminism and their place in their respective worlds. Amy Dunne, the title character of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, initially appears to be a nonentity. For the first half of the book, we know her only through the lens of her unfaithful husband Nick as she goes missing on her birthday and evidence points more and more to Nick’s culpability. That’s when the book throws us for a loop by revealing that Amy is in fact an utter sociopath, and since learning of Nick’s affair has fabricated a mountain of evidence against him before leaving town to let him take the fall for her murder. On the surface level, Amy as a character definitely has her issues from a feminist perspective, but what we see of her true voice gives us the image of not just a brilliant, devious woman hellbent on revenge but of someone lashing out at patriarchy as viciously as possible. Soon after Amy’s true nature is revealed, she goes on an extended tear against the “Cool Girl,” a type of person she argues doesn’t actually exist, but rather is a sophomoric male fantasy some women are smart enough to exploit. “And if you’re not a Cool Girl, I beg you not to believe that your man doesn’t want the Cool Girl…there are variations to the window dressing, but believe me, he wants Cool Girl, who is basically the girl who likes every fucking thing he likes and doesn’t ever complain. (How do you know you’re not Cool Girl? Because he says things like: ‘I like strong women.’ If he says that to you, he will at some point fuck someone else. Because ‘I like strong women’ is code for “I hate strong women.’)” Amy’s dissertation echoes similar criticisms of character types like the Manic Pixie Dream Girl—a character with no backstory, hopes, fears or objectives of her own, who exists only in relation to a male protagonist and how her existence makes him feel. In a patriarchal society, it’s hard to process the existence of a woman as ruthless as Amy, simply because we are trained not to expect women to have enough autonomy to be that ruthless. In George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series (and Game of Thrones, the series based on it), Queen Cersei Lannister similarly starts out seeming like exactly the kind of female character we’re expected to hate without reservation. A scheming, manipulative alcoholic engaged in an affair with her twin brother, Cersei’s machinations lead to the death of her husband and his advisor Ned Stark (the series’ nominal hero up to that point) and the coronation of her psychotic son as king. But as she’s further explored, she’s given not excuses, but certainly context: forced into a loveless marriage as a way of shoring up her family’s political power, she has been raped by her husband multiple times (which, of course, is no crime at all by the standards of the medieval Europe-based society of the series), and him striking her in anger is heavily implied to be the moment she decides to have him killed. The narrative doesn’t sympathize with her exactly, but it establishes her as part of a world where becoming like her is a perfectly understandable thing for a woman to do. House of Cards is in many ways the logical endpoint of the current era of male-antihero TV, but is distinct from shows like The Sopranos, Breaking Bad and Boardwalk Empire in that its criminal protagonist’s wife is complicit, and fully supportive, from the start (the reverse has long been a bone of contention with a particularly creepy subset of fans, to the point that Anna Gunn, who played Skyler White, reported receiving death threats). Robin Wright’s Claire Underwood spent the show’s first season less developed than her husband, but it gave her a much more substantial storyline in its second, when, in a televised interview, she admits to having an abortion after being raped (in actuality, the two were entirely separate incidents). As Amanda Marcotte points out, anti-abortion activists are not depicted as turning on Claire until rumors begin swirling that she’s had an affair. It’s a pattern that anyone familiar with victim-blaming in the real world will recognize: the validity of Claire’s victimhood is contingent on whether or not she’s acceptably sexually “pure.” Amy Dunne, Claire Underwood and Cersei Lannister are all dangerous, genuinely bad people. But like male characters (and real people) who do terrible things, they are shaped by their experiences, all three of which are very much parts of the female experience in microcosm. As Marcotte writes, “I like [Claire Underwood] for the same reason I like Don Draper, philandering misogynist. Or Macbeth, murderous traitor. These characters entertain and their stories allow the audience to explore various themes and ideas beyond whether or not they're teaching us to be good people. Fictional characters do come in different genders, but that shouldn't affect how we watch and relate to them.” #FemmeFatale #Feminism #AmyDunne #GoneGirl #ClairUnderwood #HouseOfCards #SkylerWhite

CommentsComments are closed.

|

|