|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

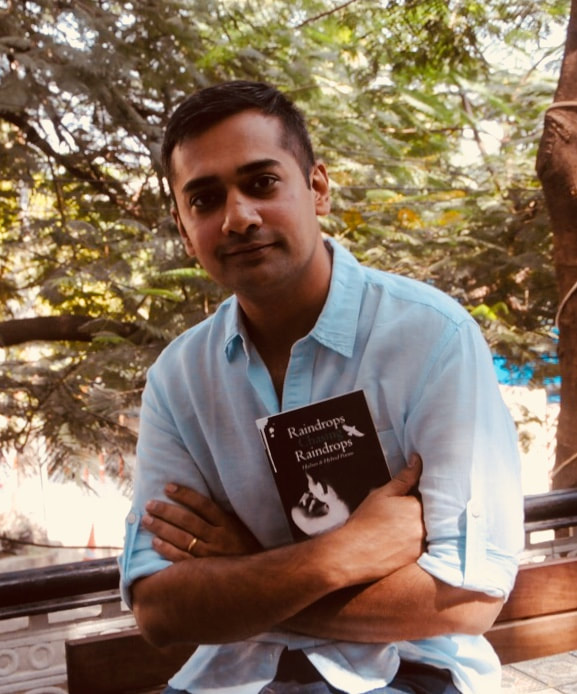

On Haiku And Hybrid PoetryParesh Tiwari is a noted Indian writer of haiku, haibun and hybrid poems. His latest collection Raindrops Chasing Raindrops is out now. In this interview with Quail Bell's Poetry Editor, Archita Mittra, he discusses the convergence of different art forms, his creative process and the publishing scene in India, among other things. Archita Mittra: As a cartoonist and a writer, how do you negotiate between the two art forms? Do you see them as separate and distinct, or as a space for hybridity? Between the two, are you more inclined to writing?

Paresh Tiwari: I believe all art forms do converge somewhere. And the convergence is life itself. And yet, I am usually in completely different mind-space while practicing these two art forms. As a poet I empathise a lot more. I try to become what I write. As a cartoonist, on the other hand, I am more of an observer. I prefer to be, rather than observe. AM: Why did you choose ‘haiku’ and ‘haibun’ as opposed to other poetic forms? Were there any cultural influences shaping your decision? PT: I discovered haiku almost serendipitously during a period of strife and pain in my life. There was creative angst but also a need to deal with personal and emotional baggage. It was then that I found a few haiku languishing in an anthology of poetry. I was smitten. I was in love. Haiku gave me peace. I found it cathartic and meditative. It helped me reflect on my life and find answers that seemed out of my reach until then. For a year or so, I wrote at least one haiku daily. And I realized that for the first time in my life, I was truly aware of my surroundings; the cerulean sky, shafts of pale sunlight through the slate-gray clouds, the hanging promise of drizzle in the gentle breeze, an impatient argument of jungle babblers, the hushed whispers of leaves, the woody aroma of wet bark all around and the deep black of a rain drenched road beneath my feet. It was liberating. Haibun was a natural next step. It was like stretching my feet further into the sun. Today, haibun is my preferred form of writing. The confluence of poetry and prose, the tapestry that one could weave is almost magical. AM: Who/ what are your influences on the type of work you create? Are there any figures you particularly admire? What are the things that inspire you? PT: The list of things and people I appreciate is long and diverse. Life, in all its messy glory, inspires me to no end. I admire writers, painters, musicians, activists, adventurers, lovers. What can I say, I have eclectic tastes. But if you push me to a corner and ask about writers and painters, the two art forms I am more closely associated with, I would have to go with (in no particular order) – Ghalib, Gulzar, Billy Collins, Haruki Murakami, Vincent Van Gogh, and Monet. AM: Based on your own experiences, what do you feel about the publishing process and the publishing scene in India? PT: It can be infuriating and heart-warming. Often simultaneously. Though the bigger publishing houses still treat poetry like a step-child, there are indie publishers out there who bring an abundance of passion, love and understanding to the table. A few names that come to mind are Red River (formerly i write) imprint, Hawakal Publishers, Zubaan books, and Copper Coin. The list of course is incomplete, but these small presses publish are rich, layered and experimental voices. They are leading the change, presenting readers with an option to the poorly written and badly edited formulaic works garbed as the next bestseller. AM: How do you locate yourself in the poetry scene in India? As an author who mostly writes in haiku, what kind of a writing community do you feel like you most belong in? PT: In that past three years or so, the sub-culture of Japanese forms has grown exponentially in the country and we are now beginning to see unique voices in the sub-genre. I believe the critical things that the Japanese forms of poetry teach – directness, brevity, suspension of cleverness, absorbing the moment, and experiencing the world afresh (to name but a few), are universal and thus would help any poet in the pursuit of involving the reader more closely. These principles would help make poetry more accessible without sacrificing its literary merits. There is a growing acceptance amongst poetry publishers and literary festivals about these new forms which is heartening. But I believe, the most important contribution of Japanese forms would be in bringing more poets to the feast. Haiku, you see makes most readers believe that they too can write. And though this belief might have its pitfalls, it also helps in liberating poetry. I, very firmly wish to belong to the camp of learners. Not just today, but for my entire life. AM: Tell us a bit more about the titles in your chapter divisions in your book. What was the creative process like? PT: My book deals with a myriad of different topics. Love, memory, family, pain, war, rebellion, dreams, mutiny, mundanity, to name a few. The problem (if I may call that) dealing with such a diverse set of themes is, how to present them in a coherent whole. The book is thus divided into four chapters moving from the outside to the inside and then to the outside again. The first chapter ‘Paper Planes’ covers a major chunk of works that fall in the category of magical realism. These are some of the more visceral and raw pieces in the collection. In this chapter, I talk to painters, poets, and surrealists who are no longer amongst us. I make love to well-thumbed books, collected melting clocks and share an umbrella with mongrels. The second chapter ‘Kintsugi’ celebrates the process of breakage and the eventual healing. ‘Postcards from the past’ as is evident from the title looks back at my life. And finally, ‘Patchwork quilt’ contains works that comment upon socio-political situation of our times. I believe an argument can be made that most of my works are memoirs, but I would like to add (and rather hastily) that I have taken liberties with the widely accepted definitions of the real and the imagined, with chronological timelines and order. AM: Do you follow a writing routine? What projects are you currently working on? Any creative ventures/plans for the future? PT: The only routine I follow, is to write wherever, whenever. I write all the time. For someone claiming that, I produce surprisingly low volume of work, but my works often germinate within me for days. I walk, bathe, eat, sleep, and wake up with memories and ideas. They keep simmering within, till their voice, colour, taste, and smell becomes mine. And that takes time. There are a few projects planned for the future, most of them elusive wisps of smoke still trying to find a foothold in my heart and mind. And then there are a few journeys, I have already embarked upon, like a collection of works dedicated to the women, I have admired and those who have inspired me. This book is likely to be a prose poetry collection with a few graphics strewn over the pages. In a not so distant future, I also wish to write a novel about the trials and tribulations of a man stuck in past. AM: What is your advice for young poets? PT: The only reason to write poetry is because you have to. Because there is no other way you rather live. Read. A lot. Established poets. Poets that you love and those you don’t. They will be your guide and your mentor. They will be your friend and co-traveller on the lonely journey that writing can often be. Edit your works relentlessly. The first draft of a poem often comes easily. Some of these initial lines might be exceptional, but the majority will need to be reworked or tossed. *~ You can purchase Paresh Tiwari’s book from these following sites: USA – https://goo.gl/EHSpsV UK – https://goo.gl/6LToJ1 India – https://goo.gl/M1NRaQYou can also check out his Goodreads Profile and follow him on Instagram. CommentsComments are closed.

|

|