|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

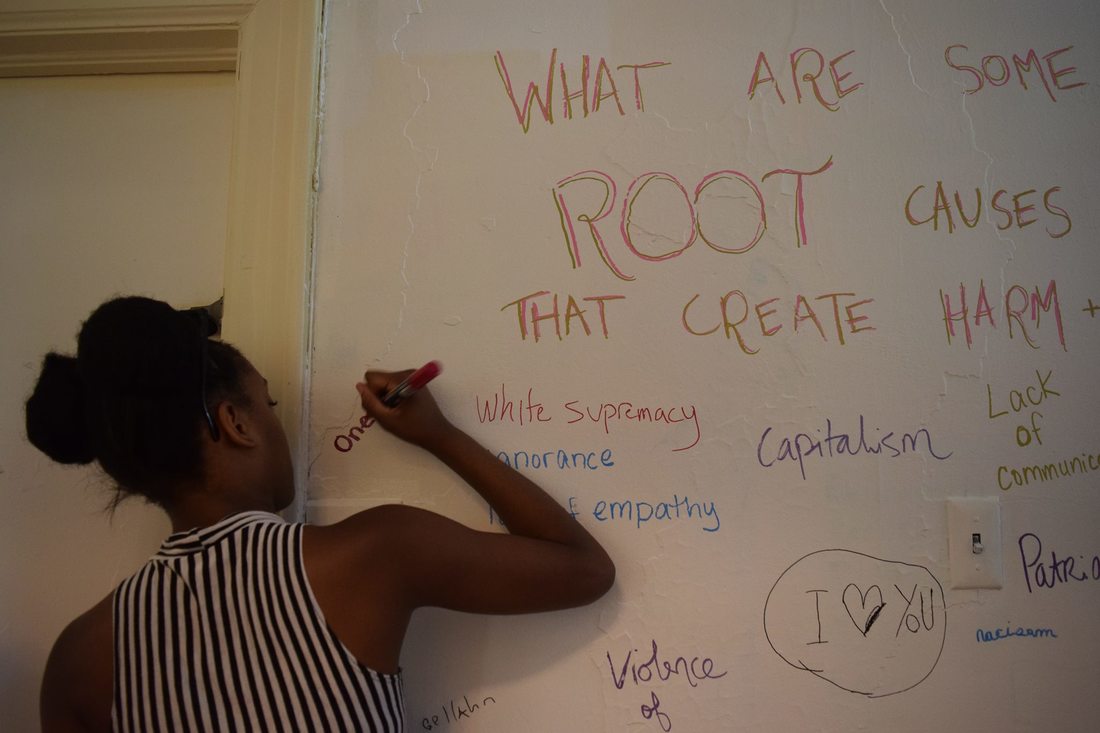

Writing On It All in Governors IslandInterview by Valentina Steiner QuailBellMagazine.com Writing On It All is a project that encourages participants to paint and write whatever they want on both the inside and outside walls of an old house in Governors Island. Participants and facilitators are given the opportunity to write or paint about anything they want, whether that is a current issue, pain, life choice, or joy they feel the urge to release onto the old house’s walls. Alexandra Chasin, the project director, is an Associate Professor of Literary Studies at Lang College, The New School. She holds an MFA in Writing from Vermont College and a PhD in Modern Thought & Literature from Stanford University. Chasin is the author of Selling Out: The Gay and Lesbian Movement Goes to Market and Kissed By, a collection of short fictions. Brief, her novella, was released as an interactive app. Her most recent book is Assassin of Youth: A Kaleidoscopic History of Harry J. Anslinger’s War on Drugs, a cultural history of drug prohibition. Alexandra Chasin took the time to do an interview with Quail Bell Magazine to discuss more about the participatory art project. Where did the name Writing on It All come from? Apart from its inferred meaning, was there more to the name? Our name is a pun on the expression “the writing is on the wall,” and because we do actually write on the walls of a house, I wanted to play with that idiom. But I wanted to shift it a little bit because with Writing On It All you get a couple of extra meanings. One is that everything can be written about, any topic, any theme, any issue. But I also wanted the project to go wider than that. Writing on the wall is already a kind of expansion of the medium by writing on unusual surfaces, but I wanted to suggest that there’s an even wider departure from the usual conventions of writing possible, so we’re not just writing on the walls, as opposed to paper, but looking at the world differently – as a set of surfaces for writing. Writing On It All is simple in design, on the one hand, but there is actually an elaborate theoretical apparatus behind it. As the artistic director, what does this title entail of you in particular? So, what it means is that I’m responsible in terms of holding and furthering the vision I was just talking about, of turning that vision into material reality. And that takes any number of forms, including talking with the facilitators, who are writers and artists, and sometimes activists, working in various media and disciplines on a range of issues or themes. Sometimes it means conveying that vision to them, so that the vision informs the otherwise radically disparate sessions that they produce. Sometimes it means talking about that vision with people who come and participate. Sometimes it means refining that vision for the purpose of writing grants – I do a lot of grant writing. I oversee the curation of the project, and I work closely with the operations manager, Zina Goodall. Technically, curation is a function of the artistic director, but Zina and I do it together, because she also has to be able to translate the spirit of the project into material reality. In practice, Writing On It All really works collaboratively – between me and Zina, between me and Zina and the facilitators, between the facilitators and the participants. And so my hope is that some of the ideas behind the project are breathed to life through that whole cast of characters. I saw that you have published some books and other short works, how do you believe your experience as a writer helps this project? That is a super interesting question. I’m going to dodge it a little to talk about my practice as a teacher. I really enjoy teaching and care about my pedagogy. But I teach in a private university, so I experience my teaching as an exclusionary practice. I love my job. I like working in an institution but it’s a bit limited by the context. With Writing On It All, I to work in a classroom without walls. I get to work with others on issues of writing, language, form, and writing practices, without, at the same time, reproducing the exclusionary institution in which I work. The project is a way of being in a classroom that runs itself as a lab. We think of the project as fundamentally experimental and there are no barriers to participation; anybody can come and do it, all you have to do is want to, which is extremely gratifying. So, I think of the project as more connected to my teaching than my writing. But there’s a huge connection, and I could go there also, with the stuff that I write and the way that I write. Yes, please, go ahead. When I trained as a disciplinary scholar, I didn’t just do literary studies, which is what I’m hired to teach now. I did literary studies in the context of the study of architecture/popular culture/technology and other cultural phenomena. So, I was trained in interdisciplinarity. Then when I started writing creatively, I found that I gravitated towards writing experimental fiction; which includes, for me, working at the border of genre, just as I work at the border of discipline, as a scholar. My most recent book, about the history of war and drugs, is a piece of nonfiction that leans heavily on literary tropes and also on creative modalities. So there’s another border that I tend to cross, the one between creative and the scholarly modes. In all my writing, I pick and choose among the inherited conventions of my genres and disciplines, conscious of the way they are reproduced in the university. That is one of the points of connection with what I was saying before about Writing on It All. My practice – whether in writing or in teaching or with respect to Writing On It All – is to question conventions of writing, and literary studies. Writing On It All is designed to encourage playing on the borders of inherited modes; it’s not about abolishing and destroying them, it’s about cross-pollinating and making the categories more ambiguous. Since you are an Associate Professor of Literary Studies at Lang College, The New School, how does this project change the way you view teaching? I’ve tried to drag in the experimentalism of Writing on It All. I tend not to enjoy teaching creative writing workshops and avoid teaching them whenever I can because I feel like the peer critique method is of limited value and I prefer to use the classroom space as a generative space. Now, I like to do writing exercises and collaborative work, which is so underemphasized in writing curricula. All of that is enhanced by or borrowed from Writing on It All, where we treat the writing space as a laboratory. In the documentary, you mention that this project flourished out of a fantasy to see a house completely covered in text, where do you think this idea embellished from? It originated with my sense that writing is decorative. I have an aesthetic appreciation of written texts. I am not sure why, but I like the look of alphabets that I can’t read, and the written texts of languages I don’t understand. I started doing some research and I saw this photograph from Russia where a person has written obsessively all over the inside of his apartment; on the furniture, on the fridge, on the inside of the fridge. It is so deeply disturbing, it looked really unhinged and so I began to rethink and research other types of precedents. There are lots of precedents for writing on both interior and exterior walls, practices that go back to ancient times in many cultures. The idea just popped in my head, like a lot of ideas. But I think it came from a sense that it would be pretty and then immediately that was complicated by seeing this disturbing example and also by the aesthetics. I’m not a person who is generally driven by an aesthetic mission, so I started thinking about other ways to conceptualize writing on a house. Why is it important that it is written on a house? I know that you mentioned you saw an example of the painting of the house in Russia. But is there another reason, is this symbolic of something? You have put your finger on the question that I have not been able to answer. Initially, I didn’t necessarily think it was going to be a house, but I did picture an architectural unit of some type. I imagined empty warehouse space, or loft space, or office space. But why a building? I don’t know and it’s been vexing to me because there ought to be a reason. So, I finesse the whole question with a gratitude for the accident that we got a hold of an empty house to do this kind of work. Have you thought about asking the people in the session, why they think it should be a house? For the first couple of years, I asked pretty much anyone who would listen. I would ask, ‘what is the non-arbitrary factor connecting writing with a building?’ I got tons of interesting answers, but none of them persuaded me that it was not fundamentally arbitrary. It is a live question and so the meta question that it suggests is: is it okay that it’s an arbitrary relationship? Does it seem to diminish authority or credibility, or something about the project if it's arbitrary? Why am I uncomfortable that I can’t answer that question? This project has been going on since 2013, why do you think it is important for people to take part in it now? This project is partly predicated on the assumption that participation is participation and that if cultural participation is supported, it affects other types of participation as well. We’ve come to a historical moment in which our relationship to culture is largely one of consumption and which puts consumers in a very passive position. Culture is very powerful; it has a lot of energy in it and can be very transformative. But you've got to engage in culture, you can’t consume it. Culture is a thing not to receive, not to wear until it is worn out – it’s a thing to practice. And again, the theory is that practice is practice, that engagement and participation are engagement and participation, and that if people participate in writing – which many people feel excluded and barred from participating in, for any number of reasons, internal and external – that if they can break that barrier, there are other arenas of participation to which the barrier might also be lowered. I believe that at this moment we are facing extreme danger having power concentrated in the hands of a relatively small group of people whose values differ so greatly from mine. Of course, many people feel the same way; that their values are different from the values of the people who control so much wealth, and so much political capital as well. The way to change that is to jump in, to participate, to practice change. I don’t have any proof. I don’t know that if you participate in one thing, you participate in another thing, but it makes intuitive sense to me. I really feel like every little bit counts. And on an empirical level, we see that when people get in the house and start writing, there’s just this little incremental freefall of disinhibition, of liberation. There’s a very tiny taboo against writing on the wall that we all walk around with, even though we are not conscious of it. We don’t suffer from the tiny taboo; it’s hardly the worst of the inhibitions under which we labor, but there it is, so when you go to write on the wall, a little bit of that taboo is released – there’s a little bit of energy and freedom there. We are not judging what people write. We are not telling them what’s wrong or right, or whether their spelling is correct, or that their sentence is incomplete. We are not judging their writing as an example of some genre or other, or asking whether it measures up to the standards of one discipline or another. We’re just letting people write. And we see some of the joy and freedom that comes from a sense of authority to do one’s own thing. I take very seriously the “author” in authority, I think Writing On It All offers way of taking back authority, of countering the centralized authority that has those terrible values and that huge monolith of power. How would you say this project fits in with the history of Governor’s Island? Do you think this adds to what the project stands for? One of the project’s four central tenets is site specificity, and there are any number of ways of addressing that value. Why is it a value? Because it pushes back against an idea of literature as something that is timeless. One of the arguments that is made for the western literary canon is that it is composed of books that transcend their time and place – books that are the best of the best that have ever been written. I think that is a very dangerous and exclusionary way to look at literature. Every act of writing is located in a particular geopolitical context and at a particular time. So, site specificity reflects that idea and we ask facilitators to try and address site specificity in their sessions. Governors Island is in the middle of the New York Harbor, which is made of water. The Island was an army base for two hundred years and then it was a coast guard station for about thirty years. Governors Island is very close to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, which are huge icons globally for both the dream of asylum and the counterfactual experience of actual people coming to New York through Ellis Island, through the New York Harbor. The house was also a domestic space used as Senior Officer Housing for the military. So a certain set of class relations has historically been at work in the house. Domestic spaces are very meaningful because we tend to spend a lot of time in such spaces. The kitchen, dining room, living room, and bedroom are hugely evocative for both facilitators and participants. We ask facilitators to consider these features of the space. We had one session where the artists worked from a colonial text about Governors Island, projecting it on the walls, and inviting participants to elaborate on that text. It often upsets people to come into an unoccupied house in a city where there is so much visible homelessness. On a practical level, no one could be living safely in these houses today because they have no running water, and are, in places, structurally unsound. So the house itself calls attention to major issues in New York City, which are homelessness and gentrification and foreclosure. We had one session all about gentrification for just that reason. This gets closer to your question of why a house, or at least how we attend to the houseness of the house. How are the session facilitators chosen? Are there any specific requirements? That is what I meant by curation; which Zina and I do together. We like to have a very diverse slate each year. In addition to all kinds of identity, we are looking for diversity of discipline and genre, because we like to define writing in the broadest and most complex possible way. So, we look for a range of people working in different media. We look for people with a record of public programming or public-facing work, or a lot of teaching (in particular, teaching in other than university settings). We’re lucky to be working in New York City because there are so many artists and writers; we reach out to local people whose work is kindred in spirit to what we are doing in Writing on It All. Is there a specific reason why the sessions change every year? We do think about that because it’s such a unique gig. The facilitators don’t always know what they are doing as they go, but then they do their sessions, and they get it. So it might make sense for them to do it more than once. This year, for the first time, we have at least one facilitator who is doing two sessions. But we also consider that one of our core purposes is to support the development of public programming amongst artists, writers, and activists who would be the facilitators, so the more different people that we pick, the more we can disseminate the model of Writing on It All, and the more we can encourage individual facilitators to go the way of public programming in their own careers. That makes sense. Also, then they can become one of the participants instead of a facilitator the next year. Oh, we’ve had that, actually. There’s some amount of cross-over, it’s fun. Do you think this project appeals more to artist and writers, or do you see a very wide-range of participants? I think that the project appeals most quickly to children. Very often we get families, and it’s the children who rush in; they know exactly what they want to do. Adults hang back a little bit but are often brought on by children. We’ve seen all different kinds of people, and it would be hard to say who gets more into it, only that the children usually get into it a little quicker. Why do are the four concepts of Collaboration, Ephemerality, Materiality, and Site Specificity so important to this project? What do they bring to the table (or should I say house)? Those four, to me, when taken together, constitute an answer back to the apparatus of what I call Literature with a capital L; that is the western cultural and economic enshrinement of literature as a particular form of culture. All of those tenets answer back some of the core mythology of western cultural production and the status of western cultural products. So, site specificity, as I said earlier, works against the idea of literature as timeless and eternal and transcending culture. Focusing on materiality counters an ancient Greek value on ideas as pure spirit, which in turn founds the modern western duality whereby the mind is superior to the body. So at Writing On It All we exaggerate the materiality of writing and the embodied nature of writers. This leapfrogs us right to ephemerality – because we are embodied and therefore we are going to die. Just like our texts, we are going to go away; we and our texts are not timeless, we and they do not last forever. Materiality and ephemerality go hand in hand because what is material is what will fade away, be eroded, degraded, and decomposed – as against a cherished western myth that great literature transcends both the body and time. The last tenet is collaboration, which is used to counter the more modern mythology of the writer as a lone genius apart from social life, politics, the marketplace, working in isolation, a little bit closer to divinity, a little bit closer to God, the whole muse idea, which also goes to a sacralizing value of culture. In fact, writing is fundamentally collaborative, which we lay bare at Writing On It All. To write is a social act. It is not the act of a genius in touch with pure spirit, it’s the act of a person living amongst people in a particular time and place. So, we have tried to craft practice that dramatizes the real nature of writing. I was going to ask why the house has to be repainted, but you just answered it with the explanation of ephemerality. Yes, also most people are so used to writing on paper and keyboards that when they write on the wall they are especially aware of the hardness and size of the surface. They’re also using unusual materials, and most people’s writing gestures are larger than they would be on a piece of paper. All of that really demonstrates the embodied experience of writing, and the physicality of the act, the implement, and the surface. Do you believe that the fact that their work is painted over gives some artists more breathing space, allowing them to write truthfully without being criticized? I do. I think we could even go to a more theoretical point there that the project is about process over product. There is no pressure on the product because there is no evaluation of the resulting text. And it’s not going to be consumed. Writing On It All is about the process of writing. The act of writing itself is what matters most, and I think participants do sense a de-emphasis on product. I do think that you’re right that that is a little bit disinhibiting. The truth is that there’s a little bit of magic about Writing On It All for two reasons. One is that there’s a little bit of magic about Governors Island itself. It’s an incredibly strange place because you’re basically in the middle of New York City. It’s a three-minute ferry ride from Manhattan, and it’s a four-minute ferry ride from Brooklyn, and yet it’s this green beautiful, old-fashioned place. You can see the skyscrapers of southern Manhattan just boom up right behind it. It’s very trippy as a place because it’s just this huge mix of terrains. There is also a little bit of magic about the process and… you just have to experience it. I can explain the project with all this language and theoretical apparatus, but in practice, when people get in there and pick up an implement and go to the wall, something special happens. The sessions for the Writing On It All project have already started. If anyone is interested in taking part in this magical experience click here for more information. CommentsComments are closed.

|

|