|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

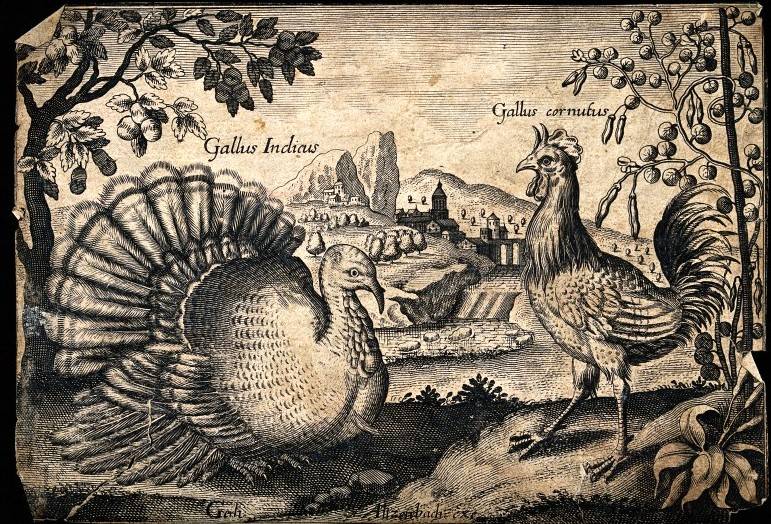

The Great Turkey DebateBy Christine Stoddard QuailBellMagazine.com Now that the remains of large Butterball birds have been carved and shoved into Tupperware, it's safe for history-lovers to squabble over who can truly lay claim to The First Thanksgiving. All of us are familiar with the Pilgrims and their Domino effect of disaster after disaster at Plymouth Rock. The Pilgrims fled England as religious refugees, boarding the Mayflower and dying like flies. Massachusetts was rough-and-tumble compared to England. The climate was harsher, the animals were bigger, and the plants were just different. But, hey, Squanto and other groovy American Indians stepped into the picture and, after a montage scene of harmonious cooperation, there was a huge feast and everybody held hands and ate and sang and later left with happy tummies. Americana eats that stuff up and then sops up the leftover gravy with a big hunk of bullshit. More and more often you'll hear that the First Thanksgiving took place in Virginia or Florida or Texas. Ten years from now, we'll be scrolling through our iPads or listening to NPR only to learn that Russian settlers in Alaska celebrated the First Thanksgiving. Or, actually, the Chinese reached California in 1249 and had some version of Thanksgiving there. Minus the pumpkin pie. But what if I told you that, even as a history fan, I don't care about where the First Thanksgiving took place? What is Thanksgiving? What does Thanksgiving mean? I don't mean it in the way they first ask you in grade school, What does Thanksgiving mean to you? I mean, what's the essence of Thanksgiving, as an event? Let's think about what actually happened in every and any version of the First Thanksgiving: Europeans “discovered” and “settled” their “newfound” piece of land, eventually realizing that they had no idea how to live off of it. The American Indians finally stopped rolling their eyes long enough to take pity on the poor bastards and showed generosity to people who had, at best, patronized and, at worst, demonized them. Because the Indians had been on the land hundreds, even thousands of years, (depending upon which Thanksgiving we're talking about), they knew the flora and fauna well enough to kill and grill whatever was then in season. Meanwhile, the Europeans had no clue. They just assumed that what worked in England or, ahem, Spain worked in the Americas, too. [Insert buzzer noise here.] Wrong! Geography and agriculture are not mutually exclusive, regardless of which God you worship. So, the Indian women and the European women cooked a whole bunch of food while the men from both sides sat around comparing weapons. They all shared a huge feast that (temporarily) relieved tension between the two groups. That was the First Thanksgiving. Whether in Massachusetts, Virginia, Florida, or Texas, it basically played out the same way. What bothers me is that we are celebrating a feast of fakery. It is a feast of fakery because the feast did not really mean peace. If it did, American Indians would not have lost over 97.7% of their land over the course of the European conquest. If Thanksgiving really meant peace, Indians would make up more than 1.01% of the total American population. 25% of Indians would not live in poverty and more than 30% would have health insurance. If you want to find out more about these statistics, check out this Wikipedia page. Clearly I am not the only one standing on this soapbox, and there's room for you to join us. Don't get me wrong: I love cranberry sauce. The right gravy makes me drool. I could eat apple pie everyday. I am not against convening with family and friends over a large, home-cooked meal and reflecting upon life's many blessings. I am against convening with family and friends in the name of some mythological event that downplays the suffering of American Indians and the many contributions they have made to American society. At best Thanksgiving says, “Look, the Europeans were idiots and the American Indians helped them out,” but it ends the story there. It doesn't point out that the Europeans never really returned the favor. If we're going to base Thanksgiving upon any historical event, we should collect a whole list of events. We should brainstorm some of the major ways one group has helped another group in need at different times in American history. We should especially concentrate on events that led to long-term peace and benefits. The spirit of Thanksgiving is about giving thanks, about feeling grateful. I am not grateful for the way things have turned out for Indians, but I am grateful that the United States has a holiday where we're reminded to count our blessings. It's the context that needs to be changed. CommentsComments are closed.

|

|