|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

Catch Her in the EyeBy Leah Mueller QuailBellMagazine.com Publishing, like most endeavors, has traditionally been the domain of white, privileged men. My image of a male novelist is Salinger-esque—a brilliant, moody recluse who neglects responsibilities, familial and otherwise, in favor of his Muse. The writer’s detached exterior hides mysteries that can’t wait to be unveiled. Such an individual is often afflicted by a ridiculous level of self-absorption. However, the image remains romantic, compelling, even sexy. It is no wonder that a starstruck girl named Joyce Maynard was thrilled to get a letter from Salinger in 1972, inviting her to live with him in New Hampshire, have his babies, and collaborate on play-writing projects.

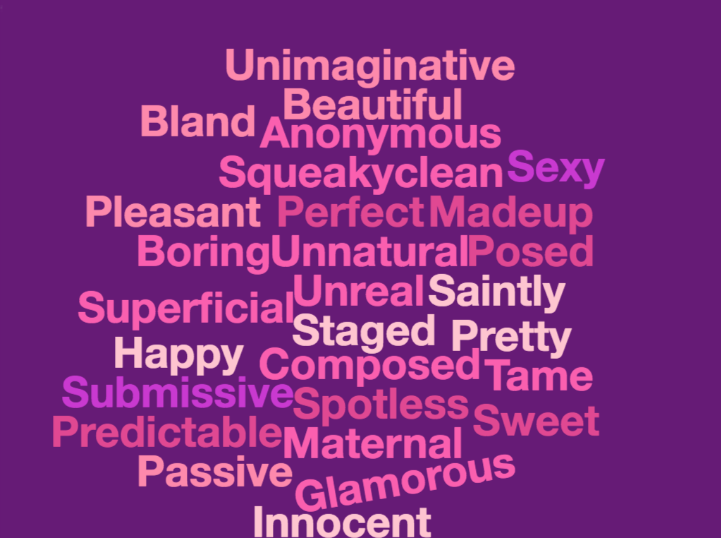

Maynard had just had her first piece published in the Times. She was 18. Salinger was 53. Maynard gave up her Yale scholarship (!), dropped out of college, and fled to Salinger’s house. Several months later, on a trip to Florida, he gave her $100 and told her to clear out. She stayed mum for years, but finally wrote a book entitled “At Home in the World” about her less-than-stellar experiences with the reclusive writer. She also auctioned off thirty letters he’d written to her, an act that elicited fury and contempt from the literary community. The backlash was intense, and women were often Maynard’s harshest detractors. In a 1999 New York Times Story, Maureen Dowd referred to Maynard as a “leech” and a “predator.” When I first glanced at the article, I was tempted to think that Dowd’s attitude was out-of-date. Sadly, it isn’t. During the first wave of the #MeToo movement, I noticed that some of the worst critics of female accusers were often other women. Whatever happened to the Sisterhood? It vanished like it never existed. #MeToo inspired a swift backlash, led by actress Catherine Deneuve (who went so far as to defend Roman Polanski’s statutory rape of a thirteen-year-old girl). She even authored a letter, signed by 100 French actresses, female academics, and other professionals, denouncing what they saw as the excesses of the movement. Deneuve’s words reinforced the tired stereotype of mens’ inability to control their lustful urges, as well as their fundamental right to express them forcefully. The letter insisted, “Men have been punished summarily, forced out of their jobs when all they did was touch someone’s knee or try to steal a kiss.” Deneuve decried the castigation of men as a “witch hunt.” Of course, the come-on that Salinger directed towards Maynard wasn’t assault. Maynard was eighteen and moved in with him of her own free will. He treated her poorly, but that’s nothing new in the annals of love. It’s easy to argue that the imbalance of power between a 53-year-old male novelist and an impressionable 18-year-old girl was inherently unfair, and Salinger held all the cards. However, most women who endure such an experience aren’t privileged enough to write a memoir about their experiences and achieve recognition. They suffer in obscurity, unable to convince anyone to hear their stories. Still, bad as Salinger’s treatment was, the reaction of the literary community to Maynard’s memoir seems worse. Female critic Caitlin Flanagan lambasted Maynard for “over-sharing”, a phrase that is seldom applied to male writers. The word “over-sharing” sounds whiny and desperate, while a male writer who divulges uncomfortable truths is usually lauded as “brutally honest” and “forthright.” Flanagan lambasted Maynard for her introspection: “Her subject is herself, and although she has but one life to live, she is never short of material, because she reads and rereads her own story according to market demands.” Audience members walked out of Maynard’s literary readings en masse, furious that she would dare to criticize such a beloved, famous man. They railed at her perceived opportunism, accusing her of exploiting her experience with Salinger to sell books. Certainly, Maynard wanted to sell books. This makes sense, since profit is one of the motives for selling a story to a large publisher. Again, male novelists indulge in tell-all behavior, reap a tidy profit, and are not criticized for it. Why the double standard? Could it be that women hold a key to dismantling sexism, but refuse to do so? If so, why? Part of it is generational, as Boomer women grew up navigating the double standard and taking it for granted. Boomer guys were still tied to the macho archetype, since many of them had grown up with images of strong, brutal men. Boys would forever be boys. A tough woman bucked up and dealt with it. Except she didn’t really deal with it. She just kept her mouth shut. Maynard didn’t keep her mouth shut, and this made a lot of people furious. She had the audacity to tell her unpleasant story, sell it to a major publisher, and make money from book sales. Oh, the humanity! Like many women of my generation, I grew up with Holden Caulfield. I read “Catcher in the Rye” at 15, and “Franny and Zooey” a few years later, while trapped in a car with my mother on an aimless trip across Mexico. I worshipped Salinger and fantasized about meeting him. The revelation that he behaved cruelly towards a young woman isn’t surprising and doesn’t dim my enjoyment of his books. It does, however, remove him from the pedestal he occupied in my mind for many years. And you know what? That’s okay. All of us need to talk about this shit. We women must speak our truths, discuss what it means to be female. We should feel free to explain how it feels to be treated like a prize to be won, and then discarded. We must criticize the continuing imbalance of power between men and women. Because if we can’t even talk about it, nothing will change. The need for honesty seems obvious to me, but I’m constantly amazed that so many people don’t get it. Many women have simply given up. An alarming number want to drag other women down for not giving up. This internalized self-loathing needs to be challenged at every possible opportunity. The well-known quote by Annie Lamont says it best: “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.” I’ll go even further and add that folks will never behave better if we don’t call them on their bullshit. This is true for both men and women, but women especially need to claim our place in the sun. The time is now. Perhaps nothing will change much, but it’s worth a shot. I’m almost 60, and not ready to give up on humans. How about you? CommentsComments are closed.

|

|