|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

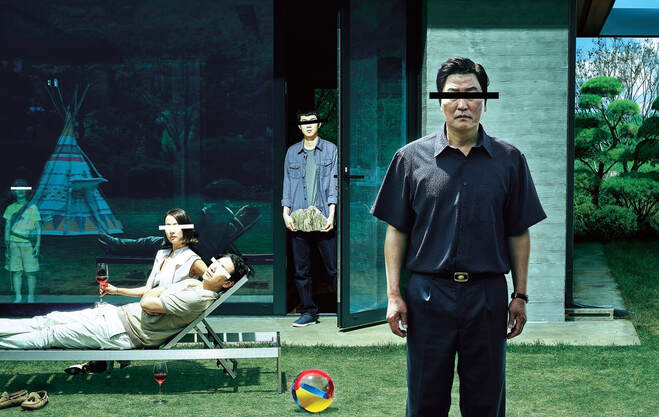

The Upstairs-Downstairs Class Warfare of ParasiteBy Mateo Vargas Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite took the international scene by storm earlier this year. It won the coveted Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in a historic feat, making it the first time a Korean director has been awarded the festival’s top prize. It’s not hard to see why the jury, headed by Mexican filmmaker Alejandro González Iñárritu, unanimously elected the genre-hopping firecracker of a crowd-pleaser as the best of the fest. It marks a triumphant return to form for Bong, the acclaimed director of vaunted, twisty familial dramas like The Host and Mother. It’s his first all-Korean production to hit screens in a decade and comes hot on the heels of his recent departure from making big budget English language sci-fi thrillers like Snowpiercer and Okja. While sharing his recent work’s penchant for biting eco-conscious social criticism, Parasite’s mesmerizing structure stands all on its own as a thrill ride of audience misdirection, upending expectations at every possible turn. The fun comes in not knowing exactly where the story is headed till it’s too late. Hitchcock would be green with envy at seeing a movie this adept at playing the audience like a piano. It’s a refreshingly exuberant pastiche of genre filmmaking at turns harrowing and hilarious, that delves into the extreme burgeoning class divide in present day South Korea. The film depicts the ploy of an impoverished family, the Kims, as they fraudulently ingratiate themselves as employees for an ultra wealthy and dim-witted Seoul family, the Parks. Through the forgery of college degree documents, Kim Ki-woo (Choi woo-sik) becomes an English tutor for the Park’s teenage daughter, passing himself off as a member of the Park’s rarefied social strata. Through deft cunning and persuasive suggestion, Ki-woo quickly manages to get members of his whole family hired in various capacities serving the Park clan (i.e. his father, Kim Ki-taek (Song Kang-ho), becomes their driver, his mother, Kim Chung-sook (Hye-jin Jang), their housemaid and his sister, Kim Ki-jung (So-dam Park), their young son’s art therapist). Within this narrative setup, Bong begins a steady careen from comedy to impending tragedy with pure aplomb, steeping every possible interaction with the possibility of eruptive violence. Yet he somehow avoids the soulless ironic detachment of post-modern cult filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and David Lynch. The emotional register of the film never falters and is always in line with the severity of the satirical proceedings. The work manages to keep all the characters, even the wealthy ones, human and believable throughout. As in Jean Renoir’s class-conscious upstairs downstairs satirical hallmark of French cinema, The Rules of the Game, every character in Parasite has their reasons.

From Park Chan-Wook’s 2003 revenge opus Oldboy to Shin Su-won’s 2015 feminist mystery Madonna, the last decade of South Korea’s national cinema has been one marked by the endemic structural violence of globalized capitalism carried out by the rich pitting themselves against the majority of the country’s population. The ensuing extremities of injustices stemming from the nation’s historical financial crises often translate themselves into cinematic carnage that is often singled out for its exceptional brutality and bloodshed. Tapping into the same cultural vein of bubbling societal malaise and class alienation facing the young hero in Lee Chang-dong’s excellent thriller from 2018, Burning, Bong cuts to the quick of the discontent, instability, and economic pressures facing many Koreans today. He also hearkens back to the unraveling of a “well-to-do” family in another touchstone of Korean cinema, 1960’s The Housemaid, in which a bourgeoisie composer becomes entangled tragically with the titular housemaid. At the outset of the film, the Kims make occasional meager wages folding pizza boxes for a local restaurant but their future prospects remain grim. The film’s mise-en-scène revolves pointedly around the link between architecture and class, opening with the Kim family dwelling, a subterranean basement apartment prone to flooding and the occasional drunk pissing in their alley. In fact, the family’s societal status as “subhuman” is sealed early on with an impromptu fumigation of the alley that seeps through their open window. They have been struggling to connect to their neighbor’s free Wi-Fi connection when the ominous cloud rolls in, smothering them indifferently like insects. In a droll moment of black humor, the family’s patriarch, unemployed driver Ki-taek, welcomes the fumigation as free pest control. The Parks, meanwhile, live in a stunning architectural marvel of a mansion designed by an esteemed architect. It has a full garage of new cars and a meticulously well-kept yard that’s surrounded by a high security walled in compound. The wife, Mrs. Park (Jo Yeo-jeong), spends most of her days in a stuporous ennui, occasionally tending to her young son, Da-song (Hyun-jun Jung), and teenage daughter, Da-hye (Ji-so Jung), as they prepare for a wondrous life of privilege. Their father, Mr. Park (Lee Sun-kyun), works as an exec in the tech industry. His open callousness when interacting with his hired help is both revolting and comical. Bong has a lot of fun skewering the ineptitude of the rich in doing any work without exploiting the labor of others. Their focus on facades of success and word of mouth is especially humorous as they insist on their hired help using “professional” English names instead of their given Korean names. The Park’s lavish living standards are extreme by any standard and the casual racism they enable in their spoiled young son’s fixation on “American Indians” is framed as a pointed critique of the obliviousness of the rich. In 2016, the IMF reported that South Korea suffers from the worst income inequality of any country in the Asia-Pacific region with the poorer half of the population owning just 2% of the country’s wealth. This comes despite the fact that in many ways, the country is one of the most educated in the world. In a 2018 study, the OECD found that “70% of 24 to 35 year-olds in the nation... have completed some form of tertiary education—the highest percentage worldwide and more than 20 percentage points above comparable attainment rates in the United States.” Despite Korea’s cultural fixation on the importance of education and tutelage, the rate of youth unemployment, depression, and suicide have steadily risen in recent years. In an irony surely not lost on American millennials, many recent college graduates find themselves stuck with low-paying jobs outside their field of study and few opportunities for advancement. The rampant nepotism in filling high-paying jobs coupled with the mass accrual of inherited familial corporate wealth has resulted in a society of extreme disparity. Obscene wealth exclusively permeates the upper echelons of the country, and there is increasing polarization and anger over the rampant inequality. Class division and anti-government sentiment reached a tipping point with mass demonstrations of over 1 million citizens in 2016 that led to the impeachment and imprisonment of President Park Geun-hye on charges of influence peddling, coercion, bribery, and abuse of power. Park’s replacement, Moon Jae-in, has also done little to inspire much hope in change for the country’s future. The younger generation has even created a popular term for this disaffected existence within Korea that speaks to the desperation and lack of future prospects many seem to face known as known as “Hell Joseon”. The seesawing of Parasite’s plot entangles the two families in a tense game where those who have the upper hand hold the keys to continued survival. The two clans become warped mirror images of one another in a way that’s reminiscent of another class conscious cinematic hit from this year, Jordan Peele’s Us. In both films, the relationship between the haves and the have nots is interrogated and complicated with such vigor and acuteness, you are left not only with thrilling cinematic art as entertainment, but also a lingering sense of dread. As the Kims become more enmeshed in the Parks upscale world, the meaning of the title Parasite is juicily dangled like a carrot for audience debate. Who is the true parasite in this tale? Is it the Kims leeching off the Parks? Or is it the Parks exploiting the labor of the Kims? Regardless of how you interpret it, the parasitic nature of class relations under late stage capitalism is dissected and skewered in a way that will make you laugh, squirm, and in a late game-changing twist, probably cry. In short, Parasite urgently asks its audience to ponder the fractured global socio-economic moment we find ourselves living in 2019 and the severity of the inescapable crisis of continued human survival under the destructive unsustainability of neoliberal capitalism. Mateo Vargas is a Mexican-American filmmaker and visual artist focusing on the intersections of identity, borders and mixed Latinx heritage. Their work seeks to deconstruct the colonial politicization/oppression of the body and indoctrination of the mind.

0 Comments

CommentsYour comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed