|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

A Literary Period Of Love & LyricismBy Rachel Rivenbark Hello, Professor Eckhardt! Thank you for taking the time to speak with us at Quail Bell Magazine. Now, you’ve been teaching at Virginia Commonwealth University for quite a long time now, nearly fifteen years. As many of our readers know, Quail Bell was founded by author/artist Christine Sloan Stoddard when she was a student at VCU, so we like to stay abreast of how VCU remains a place for creativity and stories. Your time at VCU has been very impressive. To start us off, would you be willing to give readers a bit of information about yourself, and a quick insight into what led you to teaching? I got to VCU in 2005, so I’ve been on the faculty for 14 years. Lots of things led me to teaching: I like to get in front of people, for instance, but I’m happier when I have a text to discuss once I get there. There were other things as well, though. One day in college, I was walking up the stairs to meet my adviser, an English professor. He came down the stairs, realized that he was about to miss our meeting, and said something like, "I'm going to go pick up my daughter. I'll come back a little later and we can talk then." Of course, that was fine with me. I was probably a freshman or sophomore; I was living on a very small campus; and I had virtually nothing to do but study and work a part-time student job. I figured that my dad would have enjoyed being able to leave work in the middle of the day to see his kids. Now that I routinely pick up my kids in the middle of the afternoon, I'm not so sure that it's as pure an advantage as I then thought that it would be. Nevertheless, it seemed like one at the time, and I decided that I'd stay in college as long as they'd let me.

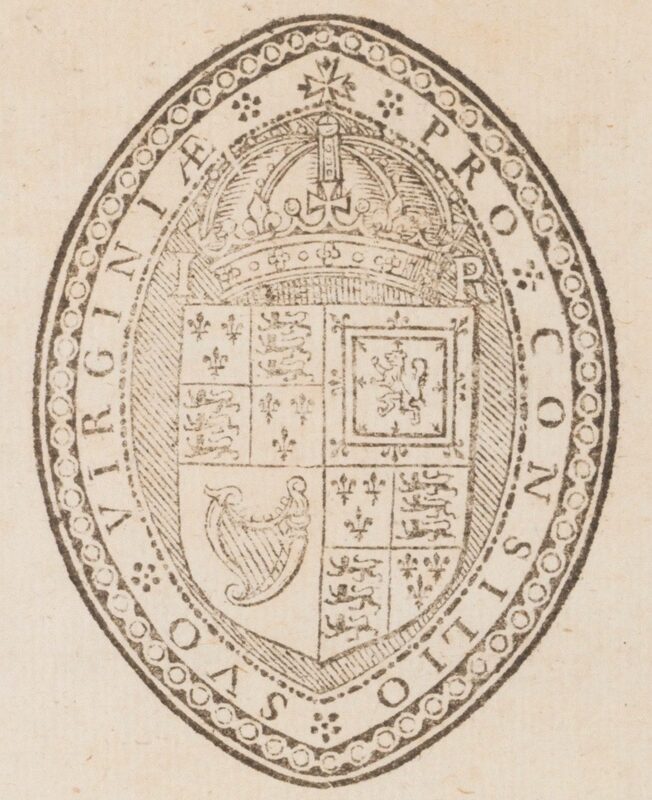

In high school, I had started reading and writing poetry especially. One summer I read through a late edition of X.J. Kennedy’s Literature textbook, which my best friend’s older brother had brought home from college. When I read my first John Donne poem, “Batter my heart, three personed God,” it was stunning. It was harsh in a way that then seemed to me uncharacteristic of religious writing, but it was totally religious. For a kid raised on rock ’n’ roll and Lutheran church, it resonated. Donne became a favorite of mine and my friend’s. So I kept reading and writing about his works, again as long as they let me. One of the most noteworthy classes that you teach at the university—in fact, the subject which you’ve chosen to specialize in—is Early Modern Literature. I’ve taken this class with you, but for the readers’ benefit, could you define for us exactly what Early Modern literature is? Early modern literature in English is basically the same as English Renaissance literature: the writing of 16th- and 17th-century England. But the change in name does have meaning. When English departments were new, they could envy older, wealthier departments that taught Greek, Latin, and Italian, or the history of art and architecture. Those departments could all lay claim to a Renaissance: a rediscovery or revival of ancient texts and forms a millennium or two after they had emerged or declined. English departments found an advantage in claiming that they had a Renaissance, too, thanks to Shakespeare, Sidney, and Spenser. Claiming an English Renaissance helped to connect fledgling English departments to one of the major interdisciplinary concerns of the university. But while English departments have grown, those older departments have gotten smaller, and therefore so has the advantage of connecting with them by claiming a Renaissance. At the same time, historical research has arguably declined at universities, and the historical research that remains has turned more and more of its attention to modern issues. By renaming the English Renaissance the early modern period, English and other departments are doing the same thing that they did with the concept of the Renaissance: they’re relating their commitments to others’ concerns. They’re suggesting that, without understanding their 16th-17th-century roots, we won’t understand much of the modern world, including (but by no means limited to) the effects of colonization and the protestant reformation. If you don’t mind my saying so, your RateMyProfessor reviews are absolutely rife with students praising the amount of passion you have for the subject. What is it about this very, very specialized field which first attracted you, and which inspires such love and enthusiasm from you? At first, I think that I just liked reading poetry that I could understand, with difficulty, but that contained no romanticism. It had plenty of lyricism and plenty of love—plenty of emotion and introspection—but none of the romantic elevation of the artist and the self. Speaking from experience, I can say that you take a very unique approach to teaching this course. Rather than simply assigning essays and other original writing assignments (the backbone of the average, more traditional English course), you encourage a certain level of historical reenactment in the course by having your students create a hand-bound and hand-written “commonplace book” throughout the semester. You even encourage the use of the original quill-and-inkwell method, where possible. What was the motivation behind reviving this ancient approach, and how do you think it affects the way students engage with the material? The main motivation was to give students a very easy way both to earn credit for the course and to slow down and intensify their engagement with the reading. But I also like reading hand-written documents. Most of my research involves reading manuscripts produced in the 16th and 17th centuries. I often have to try figuring out how they were physically produced and used. I imagined that I’d like reading manuscripts that my students made, and that it might improve my understanding of how manuscripts could have been made and modified hundreds of years ago. Obviously, your work in your Early Modern Literature course is not the only remarkable thing you’ve done with VCU, by far. You are the head of British Virginia, which-pulling a quotation from the site, cites itself as, “a series of peer-reviewed, open-access editions of original documents related to the colony [which] illustrate both the enduring ideological discourse of English settlement in and around the James River, and the unique historical artifacts that record the area’s modern colonization.” Would you mind telling us a little bit more about this incredible preservation work you’re doing, and what you hope contemporary readers can gain from it? Each British Virginia edition reproduces just one original source: a single printed book or (in upcoming editions) a single manuscript. The edition includes the full text of the source along with a physical description of the artifact and a list of all other surviving copies of the text. Half of our editions also feature full-color images of the source, which are searchable (because we layer the images on top of our transcript). I hope that readers gain from these editions the full picture of an edition’s source: what one copy looks like, how large it is, how it was made, where it resides, where they could find other copies of it. You also mention on the website that, “Reexamining these scarce or seldom-read works reveals the subtle arguments for colonization, as well as the indirect presence of opposition voices seeking to question the moral and political assumptions behind the colonization of Virginia.” Now, this is something people just generally aren’t taught in school, that, to summarize, back in England there were people even at the time who opposed the colonization of Virginia. Why do you think this information is withheld from everyday education? The evidence for this is in the first three Virginia Company sermons, one of which is available on our site. In the introductory essay to that edition, you can see my first attempt to represent the fact that the first few preachers who addressed the Virginia Company devoted some of their sermons to defending the young company from detractors and critics. I did not expect to find anything like this in these sermons. So it took me a while to come to terms with what I was reading. Why was I so surprised, and why haven’t we been taught this? I suspect that part of the reason has to do with early modern Londoners, and part of the reason has to do with more modern people like us. For their part, Londoners did not keep up their initial objections to the Virginia Company for very long. They must have been making them in 1609, when two preachers responded to the critics. In 1610, a third preacher acted surprised that he still had to respond to them. But the evidence of their criticisms end there. Perhaps that’s just because the Virginia Company stops printing sermons for a while. Or perhaps it’s due to the peace established between Powhatan and the English colonizers—or, after that, to the attacks that Opechanacanough coordinated along the James/Powhatan River. For our part, though, I think that it might be comforting to imagine that English people could not or would not see the problems with colonization when it started. Since many of the problems are obvious to us, this might mislead us to believe that we have a better perspective than they did or that we’re somehow superior ethical agents to them. But once we read 400-year-old objections to English colonization, some of the imagined ethical difference between us and them starts to diminish. What influence do you think this information could have upon the common picture which most Americans have, about what was essentially the birth of America as we know it today? Do you think or hope that people might look at the situation a little differently? I do hope so. Specifically I hope that, rather than feeling superior or dismissive, my students and British Virginia’s readers will recognize that, for our or anyone else’s objections to be preserved, people need to maintain and strengthen our collective ability to read and understand historical sources. One thing that particularly stuck out to me when I participated (albeit, for a short time) in transcribing some old documents with British Virginia was just how normal they were. I encountered poems, love songs, random tidbits of information, and - most fascinatingly - recipes for curing maladies of the time. Archaic language aside, it didn’t seem too different from your average, all-purpose scratch paper notebook. How closely do you think contemporary audiences might find that they can actually relate to these people who have been dead and gone for centuries? It helps that we all speak, or spoke, English. I imagine that some readers can relate rather closely with some writers and collectors from early modern England, since most of the language and many of the concepts and values that we have came from them. But all of those things have changed enough that they probably will and should remain rather alien to us, to some degree. I certainly find it easier to relate to other English-speaking people than I do to my German- and Spanish-speaking ancestors, because I don’t know German and am pretty bad at Spanish. There are nevertheless several things distancing a plastic-using, gas-guzzling U.S. citizen from a subject of a Tudor or Stuart monarch. Finally, to be taken in any direction you like, what is the most interesting thing you’ve found or learned, over the years of becoming an expert on these historical documents? The most interesting thing I’ve found is that, when John Donne addressed his patron in a poetic satire and joked about persecutions against Roman Catholics, his patron was collecting and preserving the official records of that persecution. Reading Donne’s poem in the context of those records reveals how risky a poem it was for Donne to write, and how great a difference a poem’s material contexts can have on its meanings. I wrote about this at the end of the first chapter in my new book, Religion Around John Donne (Penn State University Press, 2019). Is there anything else you’d like readers to know about your work, or the subject at large? Any last-second bits of wisdom or advice you’d like to impart upon our audience? I’ll just add that I’m always trying to turn attention to original sources and, when possible, to unique collections of original sources. You can see the attention to the former in British Virginia editions, since each edition displays one source. You can also see it the course on early modern literature that you’ve taken. The attention to collections shows up in my books and in other courses, such as my survey of early British literature (taught entirely from books collected by one aristocratic family) and my class on Shakespeare in the (book) stall, in which we read whatever stationers sold alongside Shakespeare’s non-dramatic poems. Thank you again so very much for taking the time to speak with me, to our readers, about the incredible work you do. I very much look forward to seeing what is yet to come, from you and from British Virginia.

0 Comments

CommentsYour comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed