|

The Breadcrumbs widget will appear here on the published site.

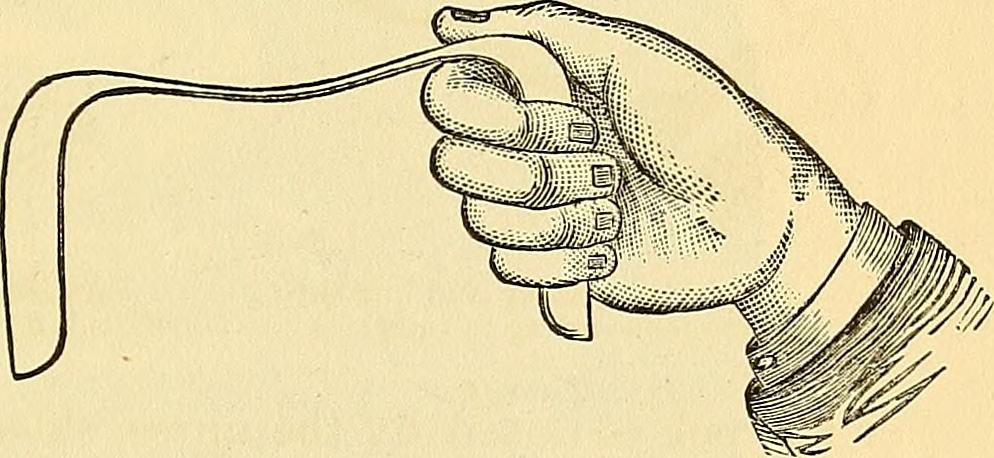

By Susann Cokal Editor's Note: This piece previously appeared in Gemini Magazine. Author's Introductory Note: The reason to write and read historical fiction is, I think, primarily to experience a story that couldn’t have been told at the time, one for which the historical record may be spotty. Such a story requires both research and leaps of imagination and emotion. My portrayal of J. Marion Sims comes directly from his autobiography, The Story of My Life, which can be read in its entirety online. In what follows, I’ve italicized passages taken directly from Sims’s book or from newspaper accounts. The lone exception is the paragraph that defines fistulae, which I’ve cobbled together from his descriptions. Sims got to write himself into history, but the women in his life did not. They are the vital heart of the story—Anarcha and Betsey and the nameless others who endured their experiments that led to the invention of the speculum, plus Sims’s wife and daughters, who witnessed at least part of what was going on. In fact, they speak every time someone opens up for one of those contraptions that shine light into a most riddled territory. Happily, he writes, the Negro woman does not suffer as the white woman does. They may moan—Anarcha, Betsey, and all the rest—but they do not feel in the same way as, for example, his dear Theresa. After the surgeries, nonetheless, he doses them with opium as they lie in the hospital (formerly a chicken coop) behind his house. “Just a grain more, the poor things,” urges Theresa, who has watched them venture outside with their blood-stained laundry, to hang it fleetingly out of sight. “So they can sleep.” Opium is not cheap, but giving extra to the girls makes Theresa the sweeter at night, when she is the only woman he thinks of. He measures their doses on the tip of a knife. * * * Theresa: his ideal and his idol, whom he has loved since he was eleven and she eight, in the comfortable Carolina town of their parents. He describes her variously as a fine woman, tall, handsome, a dashing girl, a fine rider, with fine accomplishments and great beauty. She was a belle with many beaux, whereas he was a pigmy. * * * If there was anything I hated, it was investigating the organs of the female pelvis. —The Story of My Life * * * Anyone would choose pain and a cure over pain without one, but how much pain must there be? They are accustomed to biting their lips to muffle their grief. The masters shudder at the sight of them and the wives won’t even look. They are not allowed in houses because of the smell, and the overseers use the whip in the fields, believing their foulness will ruin the crops. As they are now, they can’t make more babies, and thus they cost in profit. Anyway, it’s not up to dark girls to choose the kind of hurt they get. * * * 1835: He goes home to Lancaster at age twenty-two, a full- fledged doctor. His first two patients (babies who should have lived) die. His third (a drunk who should have died) lives, and rewards him handsomely. Fleeing failure, he settles into the hamlet of Mount Meigs, Alabama, where the county’s two other doctors still believe in letting blood. He does well in comparison, particularly after diagnosing a mysterious lump in an overseer’s abdomen. He defies the other men’s orders and cuts into the mass, and (in what he will recall as one of the happiest moments of his life) it gushes more than two quarts of deadly pus. Abscess. Within months, the patient is well enough to marry a widow and move to Texas, where he grows rich. Elated at this triumph, the young surgeon returns once more to Lancaster and tries to claim his Theresa. When her mother says he must wait, he takes a jaunt to Philadelphia and New York, does a stint in the Seminole War, and returns to Mount Meigs on borrowed money. All this in less than a year. It is now that he encounters Anarcha for the first time—or so his memory will write the story much later. She is a little mulatto girl winding a string at the Ashursts’ plantation. When he falls ill there with a fever, one of his fellow doctors orders her to bring a basin for blood-letting. He saves his own life by refusing the cut. * * * The number 13 has always been lucky for him. As have Fridays. * * * When he presents himself again at year’s end, Theresa cries, “Oh no!” It is not a refusal; it’s an exclamation. She feels helpless with pity—he is so pathetic after his illness, with hair fallen out and flesh melted to sinews. He shows her a rosebud he’s kept all these years, one she surrendered by her parents’ gate when she was just seventeen and stringing him along with the rest of her beaux. That tiny, meaningless rosebud for which he asked. There were so many other boys—but when she refused him, her spirits were depressed at his absence afterward. This is love, she thought then. The rosebud is now wrinkled and brown, wrapped in velvet and tied with a ribbon. The sight of it makes her heart ache. * * * In time she will bear him ten living children. Their first two, Mary and Eliza, are born in a log cabin in yet another Alabama hamlet. The walls shake with Theresa’s screams. He arranges for two more rooms to be built on; he is now earning three thousand dollars a year, mostly tending to Negroes from the plantations. This deep in the country, fevers are common and swift and recurrent. Himself nearly dies more than once; Theresa too. For health’s sake, they relocate to Montgomery on December 13, 1840, where he treats free n*ggers and Jews and sews up a white woman’s harelip. He declares firmly that he does not, however, treat women’s diseases. * * * But now it is 1845 and here is Anarcha. (Is she in fact the same one, or is the connection part of a fever dream?) Anarcha, whose story will be forever linked to his, brief as their time together will be in the measure of his years. She presents with a vast hole in the base of the bladder and extensive destruction of the posterior wall of the vagina opening into the rectum. He judges this the very worst form of vesico-vaginal fistula. Her urine (says her master, while she stands with hands folded and eyes down) runs day and night, wetting her clothes and her bed, causing a pruritas (itchiness) of her external parts and an all-permeating odor that makes her life one of suffering and disgust. Those who must be around her—they suffer and are disgusted, too. God is merciful, Sims thinks as he inspects the disfigured creature. How fortunate it is that He chose to afflict this colored girl rather than a more sensitive white one. A white girl could not tolerate the pain or the shame. Mr. Wescott, he explains, Anarcha has an affection that unfits her for the duties required of a servant. She will not die, but will never get well. Wescott begs him to try curing the girl. There is too much to lose otherwise. * * * Fistula: an extensive sloughing of the soft parts, the mother having lost control of both the bladder and the rectum. Of course, aside from death, this was about the worst accident that could have happened to the poor young girl. —The Story of My Life * * * “Anarcha?” “Betsey?” “Lucy?” “Dulcey—” “Mary—” Whoever they are, they reach for each other’s hands in the dark. Every night, names are lost; only three will be written into history. Anarcha is about seventeen. Lucy about eighteen. Betsey seventeen or eighteen. Each has borne at least one child. They call him Massa Doctor. All ages (except his) are approximate. * * * What a world has opened up! Now, with Anarcha and two others awaiting treatment, a gentle Mrs. Merrill has fallen from her horse (malicious beast) and jolted her womb from its usual spot. Her husband summons him. “Poor woman,” Theresa will murmur when he tells her. “The poor, poor woman.” And then they will make love. For now, he pushes poor Mrs. Merrill’s knees to her chest like a baby’s and pokes a finger inside—inflating her vagina with air and enabling himself to see—oh, everything, every hideous thing. Her uterus half turned upside-down in a most revolting position. Resolutely, he keeps one finger in the vagina and puts one in the anus, and he pushes up and pulls down. If only his finger were half an inch longer, he might-could get the womb into place lickety-split . . . Mrs. Merrill convulses. Proving again that ladies are known by their vulnerability to pain. * * * . . . a hole in the birth canal, or the rectum, resulting from the overlong pressure of a baby’s head during delivery. A most loathsome condition causing a woman to lose control of her excreta and greatly reducing, if not eradicating, her ability to bear further children, as her parts both inner and external are befouled with the leakage of urine at the least and safe passage to the uterus is not guaranteed . . . * * * It’s as if I’ve put my fingers into a hat, he thinks. He releases Mrs. Merrill; she collapses onto her side. And suddenly air explodes from her with a thunder never heard in war or peacetime. She is exceedingly mortified: “I am so ashamed.” He allows, politely, that none of this is her fault. * * * He has never grown much of a beard and so shaves himself clean. His lips sit pale in a vast plane of skin, beneath a strong and straight nose. In their early years, Theresa was fond of kissing that nose, and the gesture became habit. She tells the children (sons as well as daughters now) to kiss him on the cheek. * * * He is inspired. Mrs. Merrill has inspired him. On the way home he stops and buys a pewter spoon. Then to his office, where he collects two medical students to come to the backyard hospital. He gets Betsey onto a table. The students hold each side of her pelvis and pull her buttocks apart. Air whistles into Betsey’s vagina, filling it like a hot-air balloon. He bends the spoon handle. * * * In the coop at night, the girls hold their breath. They are leaking into the bedclothes, into their own clothes. Life’s blood, life’s excrement. The reek of it all overwhelms them. The youngest ones weep, being gone from their babies. Being held down and pried open, hollowed out and sewn shut. “There’s plenty to eat,” says Anarcha, making the best of things that will never be good. “The mistress run a good kitchen.” Lucy saves the heels from their heavy brown bread to pack between her legs. She’s had the worst of Massa Doctor’s experiments and would rather piss on his bread than eat it. Her fever’s too high to keep food inside anyway. “Darkest before dawn,” Massa Doctor says, each time a surgery fails. * * * He looks on them as Adam looked on the beasts once he named them. This is Theresa’s opinion, watching him walk toward the hospital-coop as if it were the grandest institution in New York. How proud he is! How firm his purpose! How different from the boy she married, and yet she sees the start of this man in her memories . . . “What’s Papa doing?” asks one child or another—their own Mary, Eliza, Carrie, Merry Christmas, Fannie, Florence—some little hand always tugging at Theresa’s skirts and presenting a prick from a needle, a rash from a three-leafed weed, a burn from a hot pan for her to kiss well again. “Papa’s taking care,” Theresa says, gazing through the window. “Papa is a great man.” Some days, despite the hospital girls’ suffering, she believes it herself. Every day, she makes sure that he thinks she believes it. There is something so needful about him. He looks inside those girls. What is there to see? * * * Introducing the bent handle of the spoon I saw everything, as no man had ever seen before. The fistula was as plain as the nose on a man’s face. * * * He writes to Wescott that he will keep Anarcha awhile longer and that he is confident of a cure. He also ransacks the country, as he tells Theresa, for other cases. He collects a dozen dark girls, three by three. They fill the old coop with their cots and their moans. Of limited use on the property but of great service to science. He makes adjustments to the pewter spoon: shortens it, pairs it, adds a hinge. Hollows the sides so the urine runs down and leaves the wound visible. He names it speculum. Or perhaps retractor. * * * Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, 1835: He is expected to write five compositions by the end of his senior year; he puts them off. Two months before graduation, the supervisor of composition sends a Negro to collect him. “Sheriff Jim” leads the future doctor (still a boy) across campus to the library--“I don’t know, sah,” he says; “you got to go.” Other boys watch their progress—leaning in doorways, peering through windows, standing on the college’s hillocks. Professor lays down the law: Composition is a necessary operation. At first he despairs of producing the required pages, his timidity in writing being so strong. He may not become a doctor after all. But then a friend persuades him to write out accounts of surgeries already performed. In the unfinished Story of My Life, this amusing incident occupies as many pages as the invention of the device for which he becomes famous. * * * The spoon instrument is only one part of the solution. Once he has it, the real experiments begin. He makes an arrangement with the girls’ owners: He will try to heal them--try—if clothes and taxes are paid for, and if they submit without fuss to his hands. He is firm in this: If a slaveowner doesn’t like his terms, that man is welcome to collect his girl and take her home. “The value is yours to lose,” he says. The masters—disgusted by the situation anyway—always agree. At the end of his life, he will write of these four years: There was never a time that I could not, at any day, have had a subject for operation. And: I kept all these negroes at my own expense all the time. As a matter of course this was an enormous tax for a young doctor in country practice. Naturally he laments the dropping away of interest among the town’s other doctors, who at first were so keen to witness the surgeries and examine the speculum that there would be a dozen or more looking on. Repeated failures tire them all, until he is hard pressed to secure the assistance of any one. An older doctor scolds him: “We have watched you, and sympathized with you; but your friends here have seen that of late you are doing too much work, and that you are breaking down. And, besides, I must tell you frankly that with your young and growing family it is unjust to them to continue in this way, and carry on this series of experiments. My advice to you is to resign the whole subject and give it up.” He refuses. “Surely it won’t be long now,” says Theresa, in those beautiful hours in their soft bed, some baby-to-be kicking gently at the mound of her belly. * * * The real story is Mama. So thinks Eliza, a very good girl. She plans to be exactly like her mother. Patience on a monument, Angel of the House. On whom perspiration is a pleasant shimmer, whose armpits smell sweetly of powder. Who sews so neatly and hugs so tenderly and is so good to the darkies, even when those mysterious girls do little but laze about in the yard. Mama is kind. Mama is a lady. But Papa’s the one with the fame. * * * Time after time, child after child, Theresa fulfills the marriage debt between sun-bleached sheets that crackle with starch, the crochet bedspread riding demurely on top. “You are so wet, my love,” he breathes above her. “How you welcome me!” It’s the children. Two, four, six. Like the women in the coop, she packs her cleft with rags all month long. She never tells him. He never notices. * * * “Describe the sensation,” he commands them: Anarcha, Betsey, Lucy, each one. “How does it change when I press here—or here? When I cut apart, when I stitch together?” Pain, that’s what every one of them calls it. Pain, Massa Doctor. “But what kind of pain?” he presses—questions as well as wombs. “A stab? A pinch? A burn?” A grunt. With two boys holding them pinned to the table. * * * All the Lucys, all the Betseys, all the unnamed girls do one thing alike: They tuck pebbles into their sleeves to suck on during the long, hot, thirsty nights. Some also hoard their opium, to take when they need relief from more than mere pain. The bitter taste on the tongue, the dreaminess after . . .the itching, the sweats. * * * In the country club lounges, Montgomery’s surgeons point out that some among them have been using ether now for a decade and a half. Nobody looks at him in particular, but he defends himself anyway: “The cost of ether and of a man to oversee it can best be spared for other uses. My invented speculum spoon catches the pain anyway.” Remembering the old doctor’s scolding, he adds virtuously, “I have a young family to feed. A wife who is not well.” They share a cigar and a brandy, brooding over the delicacy of pale women in hot summers. * * * The company sat down to the table about ten o’clock, and from then on until a late hour there was literally “a feast of reason and a flow of soul.” In the center of the table was a beautiful stand of flowers, and above it a wreath, in the center of which the word “Sims” was most artistically arranged in flowers. Altogether the evening was one long to be remembered by all who were present. —“Arrival of Dr. J. Marion Sims—the Courtesies extended to him while in Montgomery,” from The Montgomery Advertiser, 1877. * * * At times, despite Theresa’s patient encouragement, his spirits are depressed. Two surgeries, five surgeries, six, a dozen, and still Betsey is unrepaired. He suspects her of picking at the silken stitches at night. He suspects all the dark girls of doing this for each other, to avoid the work from which his experiments are sparing them. They are not so stupid after all. When they read the mood on his face, they offer encouragement. “One time more, Massa Doctor,” says Lucy. “I won’ scream.” She’s the one into whom he sewed a sponge, believing it would take care of the urine. The sponge turned to stone from the minerals she excreted, and he admitted her agony was extreme. “Try, sah,” she says. He still believes. He picks up his tools. * * * “Papa is a visionary,” Theresa says to Merry Christmas, when the sobs from the hospital-coop carry up to the house. “It’s all for the greater good.” Is he going to use that—thing—on her? And her girls? She clutches them to her, every chance she gets. Her beautiful, brave little girls. * * * Betsey, lying directly beneath the soft wood ceiling, takes the pebble from her mouth and uses it to scratch her name: BetSEy. betSye. BEtseY. Over and over, in shaky letters. She is the only one who can write at all. “You better rub all that out before the folks see,” says Anarcha. “They’ll never look,” says Lucy. “Scratch my name next.” “Better not,” Anarcha says. “Better do.” Betsey compromises, as girls learn to do in close quarters. She carves names on the ceiling and walls. Then she scribbles them out till they’re indistinguishable from the chickens’ claw marks. * * * May 1849: Three weeks without a surgery, and his spirits are low; but his mind is abuzz. He lies beside Theresa, unable to sleep, worrying the edge of the sheet with damp fingers. Feeling the faint trace of the stitches that keep the edge neat. Suddenly (at last) he knows what to do, and he is so taken with the idea that he must shake his wife awake. “The suture!” he exclaims, so loudly the bed frame shakes. Her wide eyes blink at him in the weak light from the yard, at the other end of which the dark girls are sleeping. “Shhh,” she says. “The children.” But she lets him say what he wants to say. She considers this her duty. * * * He puts his idea to work the next day, loading Anarcha’s fistula with lead grommets, threading silver wire (not silk) between. It is her thirtieth surgery. And a few days later—at last--The urine came from the bladder as clear and as limpid as spring water, he will recall some thirty (coincidence) years later, in the memoirs he will not live to finish. With a palpitating heart and an anxious mind, he writes down the telescoping decades, I turned her on her side, introduced the speculum, and there lay the suture apparatus just exactly as I had placed it. There was no inflammation, there was no tumefaction, nothing unnatural, and a very perfect union of the little fistula. It is just two weeks more before Lucy and Betsey are cured as well, and he packs them off to—whatever were the plantations from whence he borrowed them. * * * In later years, when he moves his family to New York in hopes that the cooler climate will be kinder to his troubled bowels, he will lecture on his treatment for fistula and his inventions for examining the loathsome female pelvis. The illustrations for his talks will feature white women. Pale flesh, no hair. “And what became of them?” a student will ask, more rarely than he might expect. “Did the surgeries hold? Did they have other children?” “They never found reason to see me again,” he will answer. This much is true even if the pictures are deceptive: he will never hear from the hospital girls again, or their masters. * * * As the news of the first girls’ cure flies through Montgomery, the doorbell begins ringing constantly—slaves sent to bring the Massa Doctor to white women of quality. The white wives beg for relief—for ether and opium. For sleep. Not surgery. “Ether is the true danger in surgery,” he explains to them as he has to his fellow doctors. He reminds himself to be patient. “The procedure is not painful enough to justify the trouble and risk of anaesthetic.” The women shriek at the sight of his instruments, at the slightest brush of his hand. They’d rather live with holes in their tender parts than endure his spoons, knives, and needles. Even when he at last offers ether, even when he says he’ll do the surgery without charge. All he needs is one white woman of good birth—one who can tell her friends, discreetly, that he fixed her. One whose name he will not list among patients in his articles and memoirs, but one who’ll encourage others to follow. “Perhaps it’s only darkies who can be repaired,” he whispers to Theresa in the night, when her arm is a gentle weight around his waist. Her breath is even and her lids never flutter. Still, he knows she is only pretending to sleep. He decides to kiss her awake. “Sleeping Beauty,” he murmurs, though her beauty has faded like the rosebud he still cherishes. She tells him, “I’m pregnant again.” Ah, Theresa, breathing softly in the moonlight! * * * On their home plantations, working in their own masters’ houses and fields, the girls conceive fast. Please, Lord, they pray into the sun. Please don’t let that happen again. They steal butter and lard from the coldroom and grease themselves as the time grows near. Please send this baby fast. Please make them stitches hold tight. Though the stitches came out long ago, the girls cling to memory to keep themselves whole. When the pain comes, there’s no one to hold them on the table. There’s no table, either. The colored midwives make them walk back and forth to shake the babies loose. And then there’s the war. * * * Triumph. Alabama to New York to Dublin, Paris, and beyond; back to New York, back to Alabama. Daring surgeries to cure hysteria and mental illness among poverty-stricken women: removal of the ovaries, removal of the clitoris. President of the American Medical Association for one year. More travels. During the War Between the States he begins a journey through Europe, leaving Theresa ensconced in their home in New York. He writes to her frequently. They are still ardently in love after four decades, especially now that she has dropped a discreet word in one neighbor’s ear, then another’s, to take away the taint of surgery on slaves. Theresa, so trustworthy, so fine. In Baden-Baden to seek relief for the pain of his bowels, he rubs elbows with royalty and nobles. Empress Eugénie of France becomes a particular friend, one who suffers through diphtheria but does not complain. He ministers to her and never even hints to others that he has cured her, too, of a fistula. White women, he concludes, can be brave despite their sensitivities. He’ll be dead in Manhattan, 1883, with deep mental depression related to the disease of his heart. His memoirs to be completed with appendices by one of his sons. * * * It was evidently through his superlative qualities of character and heart, and rare grace of manner, combined with his irresistible personal presence, that he won the exceptional popularity he everywhere enjoyed amongst men and women, not only in the higher circles of society, but in the humble walks of life. —Remarks of Dr. A. Y. P. Garnett at the Memorial Meeting of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia, at the National Capital, in Honor of Dr. J. Marion Sims, held November 21, 1883. * * * The next white man who buys the Montgomery property, or maybe the man after him, will look at Betsey’s scratch marks in the hospital coop and say, “Damn chickens.” And, “Place stinks too much to keep.” He’ll tear down the coop and leave the wood out back for the darkies to burn in their houses. * * * The girls—Anarcha, Betsey, Lucy, and the rest—don’t hear that he’s passed. If they’re alive themselves, they’re mammies now, still working for the white folks who once owned them, and nobody thinks to tell them about Massa Doctor. Anyway, there can be no sorrow in the loss, only in the having-been. Their time in his chicken coop is a memory callused over, grown hard as the sponge left inside Lucy during a bad experiment. Any one of his girls would call herself glad to be free of the infernal fistula; but time with Massa Doctor is a memory of pain measured out in pewter spoonfuls. * * * “I think I remember Anarcha,” whispers Eliza. “There was a Lucy,” Carrie whispers back. “And a Betsey,” says Merry Christmas. They hide the whispers by blotting their eyes and blowing their noses with black-hemmed hankies. The air reeks of dye; some of them chose to color their old things rather than spend much on readymade mourning. They look sideways at Mama, who sits dry-eyed at the end of the row, her hands clutching a scrap of worn velvet tied with pink ribbon. She has grown very old and quite deaf, but she is still their stalwart Mama. “Do you suppose he ever used . . . it . . . on her?” Fannie asks. “Shut your mouth!” Eliza cries, and she covers her own face with a hankie. His sleepless industry, his anxious toil, and his sublime fidelity to purpose, carved out these surgical devices and appliances which have made his name so justly famous . . . The daughters who have borne children shift in their chairs. Which of them is afflicted? They’re too embarrassed to say. “Was there an Esther?” Fannie guesses. “I don’t think so,” says Mary. Mama interrupts, so loudly the mourners in the back of the hall must be able to hear her: “Mind your manners, girls.” She gazes steadily ahead at the flowers, the lectern, the old men with whiskers. “And hold your tongues. Doctors are speaking.” Against the palm of her hand, inside her glove, she holds the remains of the long-ago rosebud. The petals have crumpled away but the stick still remains, prickly with unbroken thorns.

0 Comments

CommentsYour comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed